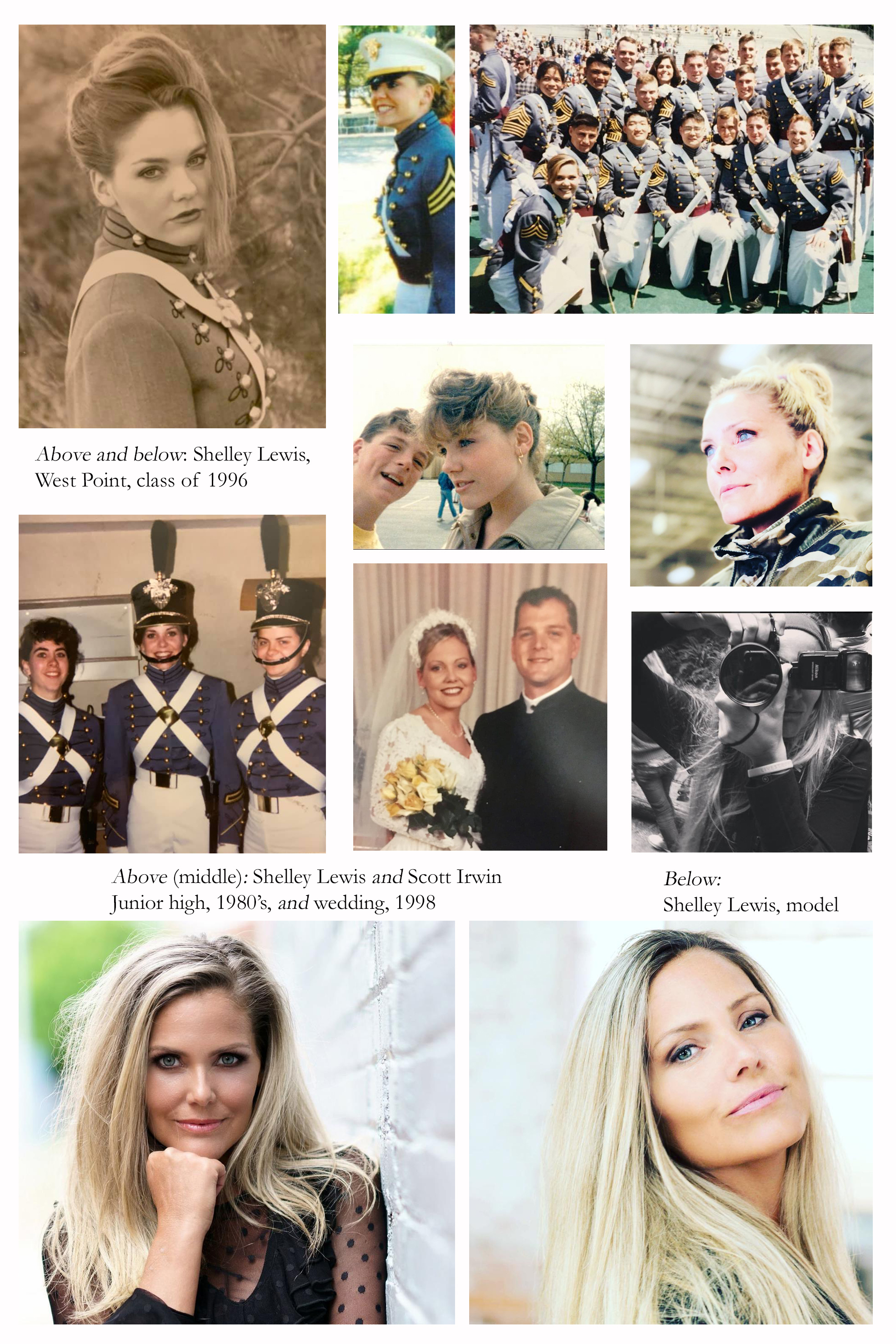

1

FROM THAT DAY FORWARD, SHELLEY LEWIS knew exactly what she was going to do with her life. Ronald Reagan was still president when astronaut Alan B. Shepard walked into the room. The thirteen year-old was literally star struck. And she had good reason to be. After all, this was space camp. Everything changed in that moment. Shelley Lewis was now quite certain of it. She wasn’t only going to be an astronaut.

She was going to be the first woman to walk on the moon.

Shelley was sitting on her son’s bed when I called her on the phone. The time read 4:50 in the morning from my end in Ireland, nearly 9 pm at night in Sacramento. I had slept little. Her house was being readied for the market, and for the duration of our interview, Shelley gazed back upon the stranger who would influence the events of her life so profoundly from a blow up air mattress.

“While we were there it was very militant,” she recalled of her days at space camp. And she loved it. “You had to make your bed every day. You had to get up. You had formation. They had deadlines. I was a payload specialist. They showed us how astronauts train underwater. So we did that. We would be building things underwater. Everything that you do as an astronaut, we did all the training.” The Challenger explosion was still very much a hot topic for discussion. The moment however that would forever alter the suppositions which construed her reality arrived while they were seated in a large room, she said, “where everything was 3-D. We were looking at all these stars through 3-D glasses, and you could see asteroids coming at you. And it was a big omnimax sort of theater. They had screens all around you. So when you looked to the left you could see things coming at you, and when you looked to the right, things came at you, and so it was a totally multidimensional experience. And then Alan Shepherd came up and started talking to us about being an astronaut and what it was like, and he took questions. He told his story about how he went to the academy and how he was selected and what a rigorous thing it was to become an astronaut.”

“I was star struck,” literally, “I just remember being completely star struck.” This is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

2

NOW, SCOTT IRWIN WAS BORN with a cleft hand. Through a series of varying surgeries Irwin was able to form full use of it, but the hand itself was always recognizably deformed. Lewis had met Irwin in the seventh grade, a year before space camp. “We were neighbors—buddies. I had been buddies with him since I was little. He would walk me home from school. And I always had a crush on him.” His feelings were mutual. “But we never dated. We went to different high schools. He always played soccer from the time he was 4 or 5 years old, and I always ran cross country.” So when he would play soccer against her high school, Shelley made a habit of looking for him.

More specifically, she’d be running cross country, a route which would inevitably bend past the soccer field. She knew to look for him and he knew to look for her.

From her sons air mattress, where she spoke with me on the phone, Shelley seemed to smile.

“He’d always come and find me,” she said.

Meanwhile, as Irwin flirted recklessly from the soccer field, Shelley Lewis went about studying everything she could about the lives of her heroes, Shepard, Aldrin, and Armstrong. “I wanted to go to West Point because, even though Alan B. Shepard went to the naval academy, I wasn’t a fan of big ships. I didn’t like getting sea sick.”

The army rarely needed rinsed of the salty sea breeze. Let the navy deal with it. Clearly, a better fit. But herein another problem arose. Lewis didn’t have perfect vision—potentially disastrous for a young hopeful helicopter pilot. “So I actually went to an eye doctor to give me those gas permeable lenses that would allow the stigmatism in my eyes to correct for me—for the short duration that would allow me to pass the test to be a pilot.”

Shelley Lewis, graduating class of 1991, thought of everything.

“I spent my entire high school career attempting to figure out how I was going to get into west point. I would spend so many hours in the career center eating lunch,” dreaming of the academy. “That’s what I did. I became a total nerd—yeah, a total nerd. Everything I could study about the F-15, the F-14. I knew everything about fighter pilots. I knew all about the different planes that they flew. Air Force Academy, Naval Academy, West Point; I knew what year West Point was founded, 1802.” Buzz Aldrin, he went to the Academy at West Point too.

West Point became her flight plan. And space camp was the Genesis behind all of it.

3

THE REJECTION LETTER CAME during her senior year of high school. Lewis’ SAT’s were not good enough. How was that even possible? The rejection letter was a liar.

Better luck next year, kid—Colonel Pierce Albert Rushton, Jr.

“I was absolutely devastated, because I had spent the last five years trying to get everything that I needed to do.” This included a primary nomination from her congressman. “In order to get into the Academy, it is basically following the recipe and then submitting your application in hopes that you get chosen. But really it’s a shot in the dark. It’s very difficult to get in.”

Shelley Lewis cried onto her boyfriend’s shoulder, clinching Colonel Rushton’s letter in her hands. She had no idea what the colonel’s phone number was, but she wasn’t going to let that stop her. Lewis was aiming for the moon. It was now or never. So Lewis called West Point on the phone.

Get me Colonel Rushton, she said. I’ll wait.

“Hello?” Colonel Rushton.

You don’t understand. I went to space camp. I met Alan Shepherd. I ate lunch in the career center. I did everything right. My whole life has revolved around this. I’ll scrub toilet.s I don’t care. I’ll do anything. Just let me in and I’ll scrub toilets for an entire year—Shelley.

“The fact that you just called,” Colonel Rushton told the young woman over the phone, greatly impressed, “has never happened before.”

He thought about it.

“If you want to get into the Academy that bad, your scores are high enough and you have the primary nomination.” Colonel Rushton shrugged. “You can enlist for a year and go to prep school.”

Shelley Lewis had only one reply to give.

Yes!

4

YOUNG MEN HAVE LONG ASPIRED to run off to the military in hopes of appreciating the bare bones, brick and mortar façade of basic training and barrack life, and in doing so avoid higher education (at least, temporarily); their daily regiment being funneled down to uniformed clothing options and a shaved head for all, none of which are likely to go out of style soon. West Point decided to become the paradoxical exception to the rule. Quite unlike grunt work, the Academy would not bend so low as to recruit. Contrarily, young sages would beckon and beg to have their minds reshaped. The great American institution goes all the way back to 1802. But even in high school, Shelley Lewis could have told you that. The United States Naval Academy would follow nearly half a century later, in 1845, with the U.S. Merchant Marines Academy and the Air Force Academy falling in rank in 1943 and 1954, respectively. And yet the reconditioning of an unskilled worker into someone educated beyond the requirements necessary for battle all started at West Point. Shelly Lewis arrived in the summer of 1992.

Comfortably situated on the western bank of the Hudson River, fifty miles north of New York City, West Point inhabits some of the most remarkable country on earth. Upon visiting in 1841, Englishman Charles Dickens remarked, “It could not stand on more appropriate ground, and any more beautiful can hardly be.” By the time Shelley Lewis stepped onto the campus, wearing make-up, the Boston architectural firm, ‘Cram, Goodhue, and Ferguson,’ had already long transformed the central cadet campus into a neogothic delight, of which the Cadet Chapel, cut from granite, predominately in a black and blue hue, stands as a grandiose example.

Like all students, Cadet Lewis instigated her plebe year among the sweltering heat of August. The brutality of it likely came with a sigh, for the wet season was nearly over. In October, the skies are still clear but elegantly crisp. Elongated shadows, sharply contrasted by shortened days, undoubtedly alleviated the discomfort of Lewis’ initial summer spars, as the year’s last and loveliest smile was glorified through a cobbler crust of foliage. French Absurdist, sometimes Existential philosopher Albert Camus delighted in autumn as “a second spring when every leaf is a flower,” which undoubtedly makes New England an annual garden paradise. And yet it stands to reason if West Point’s beauties are capable of being appreciated, the seasonal tranquility digested before the biting cold of winter hardens the Hudson, among the swirling maelstrom of physical exhaustion, dizzying labyrinth of sports statistics and numbers needing memorized, and the deliberate obstacles of hazing, all of which was intended to trip the cadet, and ultimately cripple them. Of the 1,300 plebes who enter the Academy each year, only 1,000 will graduate. The hope is to weed them out early.

“Once you enter West Point,” Shelley Lewis explained, “it’s in your plebe year when you are indoctrinated. It’s similar to rushing a fraternity. You have all this knowledge that you have to memorize.” Her Cadet Basic Training that summer, she referred to it as beast barracks, was a seven week program that aimed at turning civilians into West Point cadets. “And it’s basically where you have to learn a whole book of knowledge, and you’re learning all the demands of being a cadet. And as a plebe, you have all these rules and regulations that you have to do. When I showed up to my first day at West Point, it’s called R-Day…”

Shelley interrupted herself.

“And that’s the other thing. As a plebe you’re not allowed to use any acronyms or any contractions. And you only have four authorized statements.”

Yes sir.

No sir.

No thank you sir.

Sir, may I ask a question, sir?

“That’s all you’re allowed to do. But then you have all these jobs and duties and details, and you’re literally just being indoctrinated to the system. One of the things you’re not allowed to do is talk in the hallways. You are absolutely not allowed to talk in the hallways or the bathrooms. The only place where you’re kind of allowed to speak freely is in your own room, and that’s about it.”

Despite several years of devoted research into the ins and outs of Academy life, backed with an eager anticipation to cadence double time through their hardships, Cadet Lewis clearly didn’t comprehend the culture behind its rules when she got there. For one, she showed up with make-up on. But more importantly, an upperclassman saw her with make-up on.

“YOU ARE ABSOLUTELY A DISGRACE TO THIS UNIFORM! YOU GO UPSTAIRS RIGHT NOW AND WASH UP AND DON’T YOU EVER DISGRACE THIS UNIFORM AGAIN!”

Her name was Voightschild.

It was only the first of many more confrontations to come.

“She was mean.” Lewis said. “I thought when I got there, it’s ten percent—it’s like one woman in ten men. As a woman you want the support from other women who understood what it’s like to be in an all-men’s facility. To be honest, it was the women who were worse than the men. They were so mean to each other. That’s kind of how it is. Just to get accepted is really hard and competitive, but once you got there you were considered less than a woman, and then you were also considered less than a cadet. It was mental and verbal abuse. And so there was a lot of feeling inferior, feeling inadequate. You lose a lot of your own identity. And that’s what the military does. They try to break you down and make you a soldier. There’s no standing out. But at the Academy they always taught us: You’re the best of the best. You’re the elite. Be proud that you’re a cadet.”

“GET YOUR ASS UPSTAIRS! DON’T YOU EVER DISGRACE MY UNIFORM AGAIN!”

“And so, I remember running upstairs—booking it, and washing off my makeup.” Afterwards, Voightschild had it out for Cadet Lewis. In fact, she even seemed to hunt for her. “And then she’d haze me and lock me up at attention. And when they say lock you up at attention, there’s all these rules. When you’re in the hallway you have to have a perfect uniform. You can’t go into the hallway unless they have what they call a dress off. Your bunkmates would have to fix your shirt in a way that you’d look perfect. When you walk, if your uniform gets out of alignment, you’d get hazed. And then you had upper classmen. You had to give them different greetings.”

Bad to the bone, SIR!

“At the academy they completely break you down and then they try to build you back up and recreate you in their image. You had all these different sayings that you had to memorize for each classman, and when you’re there, it’s really about trying not to get kicked out, because they’re always looking for a way to kick you out. We had to memorize books. We had to memorize the front page of The New York Times. We had to know about the articles contained within The New York Times. We had to know the who, the when, the where, and the why about it. And then we had to memorize box scores on sports pages of The New York Times. And we had to memorize every single meal that we were eating—what we were having. And then we had table duties. Like, what was the desert at the meal? What was the drink at the meal? And what are we eating and how many days until we beat Navy and how many days until we beat Holy Cross? All the football days, we had to memorize all that with other things that we had to know verbatim. There’s an overload of information that you have to know each and every day. You have to polish your shoes. Your room has to be in order, and then you’re doing these intense academics. So you can’t fail your classes, and you have to be in shape. There’s simply no time.”

You’re not good enough, Cadet Lewis!

Cadet Lewis, you suck!

“If you didn’t address an upper classman by the right greeting, ‘I want you to address me with Bad to the Bone;’ if you mess that up, you get written up for that.”

I want you to address me with BEAT NAVY!

Bad to the bone, SIR!

Wrong answer, plebe!

“And then you get hazed,” she continued, practically breathless, each word flowing seamlessly from one to the next. “That’s where you go to his or her room and then they have you do uniform drills where you only have three minutes to run back to your room, change into a blue dress over white or dress grey over white, and underarms, and then you run back down and get inspected. And if you didn’t have it down he or she would waste your time. The most important thing at West Point was time, and you never had enough of it. They would waste your time to the point where you could fail classes and get kicked out. Or they would get you to march and do stupid stuff, where you’d do a left face and recite Scofield’s definition of discipline, and between each word you’d have to do a left face. And if you got it wrong you’d be hazed and screamed at and be broken down and just exhausted—to the point where you’d be kicked out because you couldn’t even do your academics. So there was always this pressure to perform and do things right and not piss anybody off because you’d get hazed.”

Hazed—and then eventually kicked out.

5

SO, THERE SHE WAS, TAKING A SHOWER in the bathroom, when upperclassman Voightschild happened upon her.

Lewis said, “I was talking to one of my classmates, asking her if she knew what time they had to be at formation. She found me standing in the shower naked, and she locked me up at attention, and starts hazing me in the shower, screaming at me…”

“YOU’RE A DISGRACE! YOU’RE A DISGRACE! YOU ARE ABSOLUTELY A DISGRACE TO THIS UNIFORM!”

Noel

JOIN OUR NEWSLETTER!

Stay up to date on the latest articles and news from Noel.

Further reading:

THE HIDDEN NIGHT: In the House of the Forests People with Karen B

SPACE FORENSICS: How Flat Earth Ruined Star Wars for Paul on the Plane

SPACE CAMP: Shelley Lewis’ Journey to the Dark Side of the Moon

AMERICAN PSYCHODRAMA: The Day the Challenger Exploded (with Rick Hummer and Shelley Lewis)

THE DEADHEAD & the Great Mystery of God: Travels with Zen Garcia

JESUS TAPE: The Night Robbie Davidson Discovered God

Everything that Was Beautiful Became Ugly: Escaping Flat Earth with Patricia Steere

Love and Marriage: Or the Shape of the Earth and the Gospel according to Rob Skiba

MR. NELSON’S CLASSROOM: Cleveland’s Hidden World of Geocentricsm (with Chris & Liz Bailey)

MISSING CURVATURE: Bob Knodel VS 8 Inches Per Mile Squared

Living Down Under on a Flat Earth: Laini Inivale Winning One for the Team

THE LAST ICONOCLAST: Charles Johnson Vs the Late Great Planet Earth