The Gospel According to Plato | aka “the Secret Doctrine” (Globe Earth and the Immortal Soul)

ONCE UPON A TIME THALES WAS OUT TAKING A WALK, counting the crystalline constellations without thinking so much as to observe his footing, when he stumbled headlong into a well. This in itself is not the great tragedy of the tale, as we are quickly informed it wasn’t merely the moon-lit terrain whom the absent-minded professor completely overlooked, but a beautiful young woman. We are uncertain whether or not she thought to extend a hand or hoist a rope and help him up as she peered down upon him, apparently still stargazing from the depth of his own doing, but all accounts certainly agree—the Greek mortal wasted no time in teasing his clumsiness.

She said: “You were so eager to know what was going on in heaven that you could not see what was before your feet!” The young girl apparently did not think much of philosophers, for she quickly added: “This is applicable to all philosophers.”

Thales, it appears, and those who followed in his footsteps, were walking daydreams.

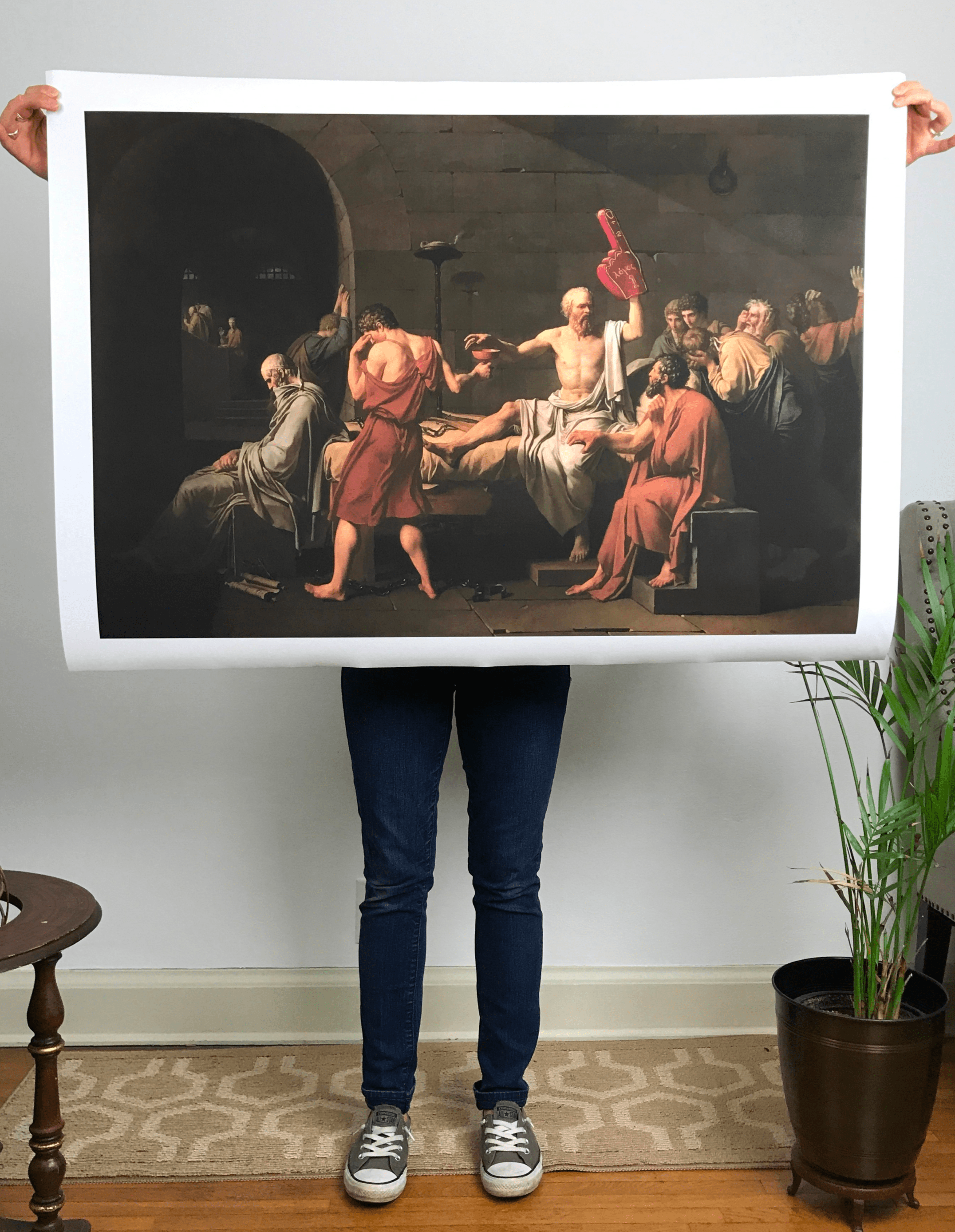

SOCRATES TOOK A VERY LONG TIME TO DIE. One day in 399 BC, having stood before a jury of his peers, the seventy year-old Greek philosopher held a cup of poisoned hemlock in his hand. He was accused and convicted of “refusing to recognize the gods acknowledged by the state” and also of “corrupting the youth” through the “introduction of new deities.” But far more importantly, he wanted a Science-hinged totalitarian society with his Socratic friends and students for its iron-fisted monarchs. To do so would dispose of democracy completely. That—or comedy killed him.

Athens had sentenced him to death by suicide, and Socrates was happy to comply. In hindsight there is little bewilderment here. The greatest humanist who-ever was could apparently do nothing without attaching a lesson of his own moral superiority to it. He drank the fully prescribed antidote of poison, but not before conducting a long-winded dialogue of such epic and philosophically perverse proportions that his would become the famous last words for the ages. He expounded on the immortal soul and, in a rather odd twist of the spiritual lemon, introduced the world to spherical earth. With the suicide of Socrates, globe earth was unquestionably born upon the assembly line of existence.

Plato was not there to see his teacher’s punishment carried out. Phaedo however was. It is Phaedo who records his famous last words, even going so far as to name the closing dialogue of Socrates life after himself, and immediately we have a problem. While the nagging rumor that Socrates never existed shall not be discussed nor theorized here—particularly because both Socratic schoolmates and contemporary playwrights, as well as his laundry list of political enemies, all lend credibility to his existence—it is the character of Socrates, as delivered to us on Plato’s delectable platter, which presents us with another quandary entirely. Diogenes Laertius (180-240 AD), wrote in The Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers:

“They say that, on hearing Plato read the Lysis, Socrates exclaimed, ‘By Heracles, what a number of lies this young man is telling about me!’ for he has included in the dialogue much that Socrates never said.”

Plato had a habit of publishing lies.

It is Plato, in his dialogues Theaetetus, who accredits the story of the astrologer who fell into a well some two-hundred years earlier to Thales (624-546 BC), as opposed to Thales own contemporary, Aesop (620-564), who managed to tell the same parable while failing to identify his source of inspiration. Plato not only had a habit of mocking pre-Socratic philosophers, but as histories great plagiarist, often failed to deliver proper credit to the ideas which he claimed as his own. I am of the opinion that Thales did not write his own teachings down, like Pythagoras after him. To do so would break the code of silence among neophytes and closely guarded secrets of the Mystery schools. It is the very reason why Socrates refused to be initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries. Membership, he said, would seal his tongue. And besides, Plato would have him grin, though her sacred rites were protected even from his ear, her principles were well understood.

Though it is Plato who hoped to give Socrates credit for first dispensing knowledge of the immortal soul, Laertius cautiously delivers the prize to Thales. “Some again…say that he was the first person who affirmed that the souls of men were immortal.” To this he added discretion. “But Aristotle and Hippias say he attributed souls also to lifeless things, forming his conjecture from the nature of the magnet and amber.”

Aristotle further clarified Thales idea of the soul. “Some think that the soul pervades the whole universe, whence perhaps came Thales’s view that everything is full of gods.” The some whom Aristotle referred to were Leucippus, Democritus, Diogenes of Apollonia, Heraclitus, and Alcmaeon, later arrivals in the Greek pantheon of philosophers who adopted Thales pantheistic view that the soul was the cause of all motion, thereby permeating and enlivening the entire cosmos.

Once again, Plato would rather direct us to Socrates—a slight of hand trick to promote himself, ultimately—rather than granting credit to Thales, when he had his tutor suggest in Apology that the heavenly luminaries were gods, even painting the soul with such epic strokes that it pervaded the entire universe. Later on in Laws, it is noted that Plato introduced an Athenian stranger who seems to give himself away as a Thales archetypal figure without ever dropping his name, and is quoted to have said: “Everyone…who has not reached the utmost verge of folly is bound to regard the soul as a god. Concerning all the stars and the moon, and concerning the years and months and all seasons, what other account shall we give than this very name—namely, that inasmuch as it has been shown that they are all caused by one or more souls…we shall declare these souls to be gods…? Is there any man that agrees with this view who will stand hearing it denied that all things are full of gods? The response is: No man is so wrong-headed as that.”

To conclude that Thales had rejected the old gods by stating that “everything is full of gods” would be a disservice to what the pantheon of gods were ultimately intended for among the Mystery school initiated. This is the big secret, is it not? The Greek gods had hoped to direct their human pupils to their own divine potential. If the soul was immortal, then each of us is divine.

The fact that Phaedo is a fictional character, created by and serving as a convenient stand-in for an otherwise absent Plato, the integrity of his middle period dialogue (his magnum opus, The Republic, was written about the same time) is immediately discredited. Though fictional Phaedo closes his account by naming Socrates “the best and wisest and most righteous man” whom he or any of his friends had ever known, Phaedo doesn’t even attempt to convince us that he himself is in fact anything rising above the pen writer’s strokes of imaginative conjuring. Nothing here can be ascertained as moral. Plato lies. In life, we are led to believe, Socrates had a particular affinity for Apollo (or Apollyon), which the Apostle John accredits as being Satan. It was the Oracle at Delphi who reputedly pronounced, through babbling tongue-speak and an interpreter, that nobody but Socrates was wiser in all of Greece (Satan’s words, mind you), thereby securing his vocation as a philosopher. Plato used Greece’s most highly exalted celebrity, stemming from Satan’s own endorsement—backed here with the fictional witness Phaedo—to praise his own ideas.

Oh, but there’s more! Much like the long line of Pythagorean mystics before him, Plato may have only organized some rather peculiar instrumental arrangements from the occulting Mystery Religion and passed these ancient pre-deluge Nephilim-operations off as his own. While he lay on his deathbed, and with an advantageous slip of the tongue, Socrates invoked what he called the secret doctrine, which I shall hereafter refer to as the Gospel according to Plato.

And it goes something like this.

In the beginning was God—and the soul; for the soul, you see, is immortal without beginning or end. The soul cannot be murdered. It cannot experience death. Whether rewarded in heaven—the world of ultimate truth and forms—or punished among bubbling pools of mud and oozing rivers of lava within Homer’s underworld, not even death itself can destroy it. The soul is immortal. Socrates’ student Simmias—a mortalist who believed the soul is inseparable from the flesh and therefore created and destroyed with the flesh—had obviously not yet completed his Socratic training, because even on his teacher’s deathbed school awaited him. First there was the Affinity Argument for discussion, which explains how invisible, immortal, and incorporeal things like the soul are different from visible, mortal, and corporeal things, such as flesh. After securing Plato’s own tripartite model of the soul through the lips of his master, Satan’s very words to Eve in the garden are regurgitated for the consumption of mankind. Indeed, the secret doctrine, first spoken from the gardens tree, is here made known.

Satan asked Eve: “Yea, hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden?” The serpent quickly concluded. “Ye shall not surely die (Genesis 3:4).”

Eve bought it.

Except here Satan, likely disgusted by Moses’ lack of elegance in the Holy Books composition, rephrased his one-liner from Socrates own bed in a manner which seemed far more pleasing to his literal intent when the master philosopher is recorded as saying: “Now the doctrine that is taught in secret about this matter, that we men are in a kind of prison and must not set ourselves free or run away, seems to me to be weighty and not easy to understand.”

He is speaking mainly of two things. Firstly his own impending suicide; which his disciples protested in respect of their own preconceived moral high ground; and far more importantly, Socrates outlined a central tenant of Gnosticism—the fleshly prison. “…so long as we have the body, and the soul is contaminated by such an evil, we shall never attain completely what we desire, that is, the truth.”

A Pythagorean philosopher—his name is Cebes—protests: “Socrates, I agree to the other things you say, but in regard to the soul men are very prone to disbelief. They fear that when the soul leaves the body it no longer exists anywhere, and that on the day when the man dies it is destroyed and perishes, and when it leaves the body and departs from it, straightway it flies away and is no longer anywhere, scattering like a breath or smoke.”

Please, erase our doubts, Socrates.

Here Socrates expounds on the good news for the humanist religion of all ages, the body and soul who needs no Redeemer to resurrect him—the Gospel according to Plato:

“We believe, do we not, that death is the separation of the soul from the body, and that the state of being dead is the state in which the body is separated from the soul and exists alone by itself and the soul is separated from the body and exists alone by itself? Is death anything other than this?”

“It is this,” the room agreed.

“Death,” their teacher said, “is a release and separation from the body.”

For Socrates, death could not conquer the soul. In this perverse Gospel, the immortal soul of the Platonist would also be born again on his own. Accordingly, if all things that has life dies, or more specifically, if death should remain in that condition, it is inevitable that all things would be dead with nothing alive remaining. Since there is life before us, this is proof for the Platonist that the soul is immortal. Just so that there was no confusion among his friends and students, Socrates supposedly utilized the last moments of his life rephrasing and then rephrasing again his new Gospel for the ages—including, unfortunately, the church age to come, who has had a terrible habit of blending their Gospels with his—an assortment of phrases, all of which outright dismissed the final destruction awaiting the soul.

“If the immortal is also imperishable, it is impossible for the soul to perish when death comes against it,” he said. “And so, too, in the case of the immortal; if it is conceded that the immortal is imperishable, the soul would be imperishable as well as immortal.” Also, “Then when death comes to a man, his mortal part, it seems, dies, but the immortal part goes away unharmed and undestroyed, withdrawing from death.” To the Pythagorean mystic standing before him, Socrates concluded: “Then, Cebes, it is perfectly certain that the soul is immortal and imperishable, and our souls will exist somewhere in another world.”

“I cannot doubt your conclusions,” said Cebes.

Upon closer reading some will argue that Plato did not necessarily invent the globe. That assignment often falls upon the mystic Pythagoras. However, in all investigations to the original proposition of a spherical Earth, they often begin with Socrates discourse in Phaedo and, while snooping from behind the shadow of Corinthian pillars, barely manage to wander beyond the platforms of various pre-Socratic philosophers like Anaximander, who advertised earth as flat and cylinder-shaped, like a column-drum; or Thales, believing the earth to be a log of wood floating on water; or Anaximenes, theorizing a flat disc held up by air; and never mind the Biblical Hebrews, with their three-part self-enclosed and circular world; before returning henceforth to Socrates again in Phaedo. Who first invented the globe, whether fingering Pythagoras, the mystical son of Apollo; or the helios god’s chosen sage, Socrates; is not important. Why split hairs or senselessly argue over the lesser of two evils? This we can most certainly conclude; if Pythagoras made globe earth a speculation for the Mystery neophyte while hiding his face behind the curtain, Plato institutionalized the occult—and ever since has accused men as being delusional for denying it.

After conversing at length about the soul, Socrates proposes that the earth itself—though there are many wonderful regions about it, he says—“is neither in size nor in other respects such as it is supposed to be by those who habitually discourse about it.”

His student Simmias, a mortalist who believes the soul is destroyed with the flesh, asks: “What do you mean, Socrates? I have heard a good deal about the earth myself, but not what you believe; so I should like to hear it.”

We can only speculate if Simmias became globe earth’s first Socratic convert. I find it fascinating, considering what we know of his gospel, that Socrates takes an Isaiah 40:22 approach to our first descriptions of a spherical Earth, whereas the Prophet Isaiah, being a mortalist, described the earth from a vantage point which only God is allowed: “It is he that sitteth upon the circle of the earth and the inhabitants thereof are as grasshoppers (Isaiah 40:22).” To this effect Socrates says: “In the first place, the earth, when looked at from above, is in appearance streaked like one of those balls which have leather coverings in twelve pieces, and is decked with various colours, of which the colours used by painters on Earth are in a manner samples.”

And yet, while Socrates says there is nothing to prevent him from describing in greater detail what form he believes the earth to truly be, a poison cup awaits him, and his life will end before he can explain it all. After all, he has to take a bath so as not to trouble the women who tend to his corpse. Oh gee. If only he hadn’t wasted so much time blabbing on about the immortal soul.

In another of Plato’s dialogues, Timaeus—published 39 years after the death of Socrates in 360 BC and the only of his works available throughout the Middle Ages in Latin—globe earth’s provocateur attributed the Demiurge, benign architect of matter, as its creator. How interesting. We read that Plato’s idealized Creator “made the world in the form of a globe, round as from a lathe, having its extremes in every direction equidistant from the centre, the most perfect and the most like itself of all figures.”

Most stunning of all—for those of us who recognize the Mystery Religions grab at the cosmonaut today, with his astral projections and silver chord journeys into the higher realm by way of televised space walks—Socrates appears to prophesy what is to become our intended reality when he states: “…by reason of feebleness and sluggishness, we are unable to attain to the upper surface of the air; for if anyone should come to the top of the air or should get wings and fly up, he could lift his head above it and see, as fishes lift their heads out of the water and see the things in our world, so he would see things in that upper world; and, if his nature were strong enough to bear the sight, he would recognize that that is the real heaven.”

From its very conception Globe Earth, including the unbridled limits of outer space which surrounds it; or as Plato referred to space—the real heaven; is esoteric fecal matter for the minds of Blavatsky and the cosmists. Globe earth holds hands with the immortal soul and, quite tragically, the church’s preconceived notion that we shall ascend as bodiless beings into heaven. Wedded together, they are the Secret Doctrine revealed.

The Roman Poet Ennius summed up Thales tumble into the well some two-hundred years earlier, and the blunderous meeting of the two sexes to follow, when writing the obvious: “No one regards what is before his feet when searching out the regions of the sky.” Cicero came to the same conclusion. I can’t think of a better beginning to the myth of the immortal soul than the philosopher who had his thoughts so fixated upon the heavens that not even his feet had any use for him or any of us here on earth.

There’s that, and hemlock.

Socrates drank the cup and then scolded the men around him due to their incessant display of tears. This, he barked, is why he sent the women away. His misty-eyed friends were, he insisted, strange men. And then Satan’s chosen master died. Almost two and a half millennia after the concoction was administered into the old man’s mouth, one must ponder if that very cup is still being passed around today, because it seems like just about everyone, Christian and non-Christian, has drunk from it.

Noel