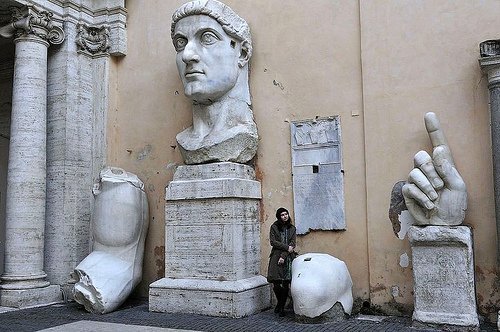

Remember When Constantine Changed the Law of God and Got Away with It?

WHY EMPEROR Maxentius chose to meet Constantine in open battle, rather than endure a siege in Rome, is a question best relegated to histories prodigious book of blunders. Rome was undoubtedly stockpiled for such an event. Evidence points to the fact that both Valerius Severus and Galerius, challengers to the Augustan throne, were successively repelled and defeated at her very gates. By 311 AD, only one more contender remained. That would be Constantine. Maxentius soon pressed his eyes upon his last and greatest threat—and declared war on him.

It was the evening prior to their meeting at the battle of the Milvian Bridge when Constantine, clearly outnumbered by Rome’s defenders, had a vision. The son of Emperor Constantius I looked upon the divine sun as it dipped into the west and beheld a flaming cross above it, with the Greek words Εν Τούτῳ Νίκα, which when translated reads: “Through this sign [you shall] conquer.” The historian Eusebius, a Constantine apologist, would write only several years after the Emperor’s death: “He saw with his own eyes the trophy of a cross of light in the heavens, above the sun, and bearing the inscription, CONQUER BY THIS. At this sight he himself was struck with amazement, and his whole army also, which followed him on this expedition, and witnessed the miracle.” Constantine’s initial confusion would be laid to rest later that night, when a man whom Constantine later—much later—claimed was the Christian Christ appeared to him in a dream and explained that he should use the cross against his enemies.

If Maxentius received any such vision, we will never know, because on the following day, the 28th of October, 312 AD, Rome’s defenders were hewn into confusion. While beginning their retreat over the Tiber River, a pontoon bridge collapsed. Many of his soldiers drowned in the escape. Others were trampled to death.

Constantine rode into Rome with the head of Maxentius.

The fledgling conqueror, twenty-four year young, was hailed Emperor and, writes historian Frank E. Smitha, “a man favored and guided by the gods.”

Though it is true that Constantine would ban the subjugation of Christian worshipers the following year with the Edict of Milan, in 313 to be exact, his stunning proclamation a decade later would, unknowingly for most today, askew the history of the world into a doctrine of lawlessness. On the 7th of March, 321 AD, Constantine decreed “the day of the sun” as Christendom’s official day of rest. In doing so, Constantine changed the true Biblical Sabbath to the first day of the creation week.

The king had no authority to do so.

To this day, Constantine’s adoption of the Christian faith is a veiled conundrum, saluting our better senses with only so much of the fleshly sheath and servile odor which a career politician is capable of exhuming. Despite a thirty-five year reign, he would not declare himself Christian until a relatively advanced age—why? The man whom the Eastern Church canonized into the coveted chair of sainthood only agreed to a deathbed baptism in 337, and by an Arian Bishop, Eusebius of Nicomedia, no less—which is strange, when one considers the Arian dispute, and ultimate drubbing, by Saint Nicholas and the Trinitarians at the Council of Nicaea in 325. Actually, come to think of it, Constantine was an unapologetic initiate of Mithras and never disowned that fact. Despite Eusebius hailing his Emperor the “new Moses,” furthermore materializing and shellacking church propaganda with his apparent Mithraic-inspired vision, Constantine minted coins depicting Mithras on one side and Christian symbols on the opposite.

And understand this. Sunday already held a special place in the hearts and minds of the pagan world. For the Mithrian cult of Constantine and his soldiers, Sunday was a most sacred day. It was called “The Venerable Day of the Sun.” The first day of the week belonged to Sol Invictus, to Mithras and to Apollo. It was a day of celebration and thanks—a day when wages were traditionally paid to workers—a day of rest. Essentially, it was a day relegated to the worship of the Beast—namely, Satan himself. And in the most irreverent fashion, Constantine decided it would be Yahweh’s day too.

The king did as it pleased him.

In History of Christianity in the Light of Modern Knowledge, Dr. Gilbert Murray, Professor of Greek at Oxford University, wrote:

“Now since Mithras was the sun, the Unconquered, and the sun was the Royal Star, the religion looked for a king whom it could serve as a representative of Mithras upon earth. The Roman Emperor seemed to be clearly indicated as the true king. In sharp contrast to Christianity, Mithraism recognized Caesar as the bearer of divine grace. It had so much acceptance that it was able to impose on the Christian world its own sun-day in place of the Sabbath; its sun’s birthday, the 25th of December, as the birthday of Jesus.”

This is not to deny the sigh of relief which accompanied Christians, who had relentlessly endured persecution and martyrdom for nearly two centuries. Initially, or rather seemingly, with the Edict of Millan, the nightmare was over. One might conclude that his administration was defined by the promotion of tolerance towards religions which had been so long oppressed—but only abstractly. By choosing religious tolerance as an instrument to bolster his reign, he slyly succeeded in bleeding the occulting Mysteries of paganism and the religion of Yahweh, as revealed through Jesus Christ, into a one world religion—namely, the Roman Catholic Church. With Constantine, pagan hordes entered the church, exchanging one priestly cloak for another, and ruled over the sheep of Yahweh’s pasture.

Much might be written concerning the Gentile and Jewish conflicts in the first century church, namely among the writings of the Apostle Paul—but Sabbath simply wasn’t one of them. There is no revision nor adjustment documented anywhere in Scripture. Had there been such a modification within the early church, bumbling Yahweh’s Day from the seventh to the first day of the creation week, then the entailing controversy would have been more explosive than the issue of circumcision. Such an event would have been unparalleled. And in fact, three centuries later, it was. Until Constantine, the fourth commandment remained unchanged since the creation itself.

The Law unequivocally states:

8 Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy.

9 Six days you shall labor and do all your work,

10 but the seventh day is a Sabbath of Yahweh your God; in it you shall not do any work, you or your son or your daughter, your male or your female servant or your cattle or your sojourner who stays with you.

11 For in six days the Lord made the heavens and the earth, the sea and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day; therefore Yahweh blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.

Exodus 20:8-11

Constantine’s lawlessness was indeed widespread in application, demanding that the follower of Yahweh find his pause on Apollo’s day rather than the day in which Yahweh sanctioned. Under the newly established Imperial church, merchants were forbidden to trade—businesses closed. Farmers alone were permitted to continue work on the Roman Sabbath, if produce was otherwise deemed impossible to manage. The Sunday law was officially confirmed by Roman Papacy. The thirty clerics who assembled at the Council of Laodicea in A.D. 364, some four decades later, decreed: “Christians shall not Judaize and be idle on Saturday but shall work on that day; but the Lord’s Day they shall especially honor, and, as being Christians, shall, if possible, do no work on that day. If, however, they are found Judaizing, they shall be shut out from Christ.”

This is undoubtedly the Big Hustle—the wool pulled over our eyes—the greatest lie in the history of Christendom. To obey Yahweh rather than man was not only relegated to Judaizing, but rather perversely, to a total loss of salvation. The Law itself became irreverent. And the church bought it. This is undoubtedly due to the fact that the spirit of lawlessness was already at work. Apostasy abounded. We observe Sunday instead of Sabbath worship because the Catholic Church in the Council of Laodicea transferred the solemnity from Saturday to Sunday. They had no Scriptural authority to do so.

In hindsight, Constantine was perhaps the greatest antichrist in history—because, where history is concerned, including present history, he changed the times spoken about by the Prophet Daniel, and got away with it.

-Noel