He Found the Oracle of Tomorrow: Copernicus, Meet Hypatia

SOME SAY the dark ages began that very day.

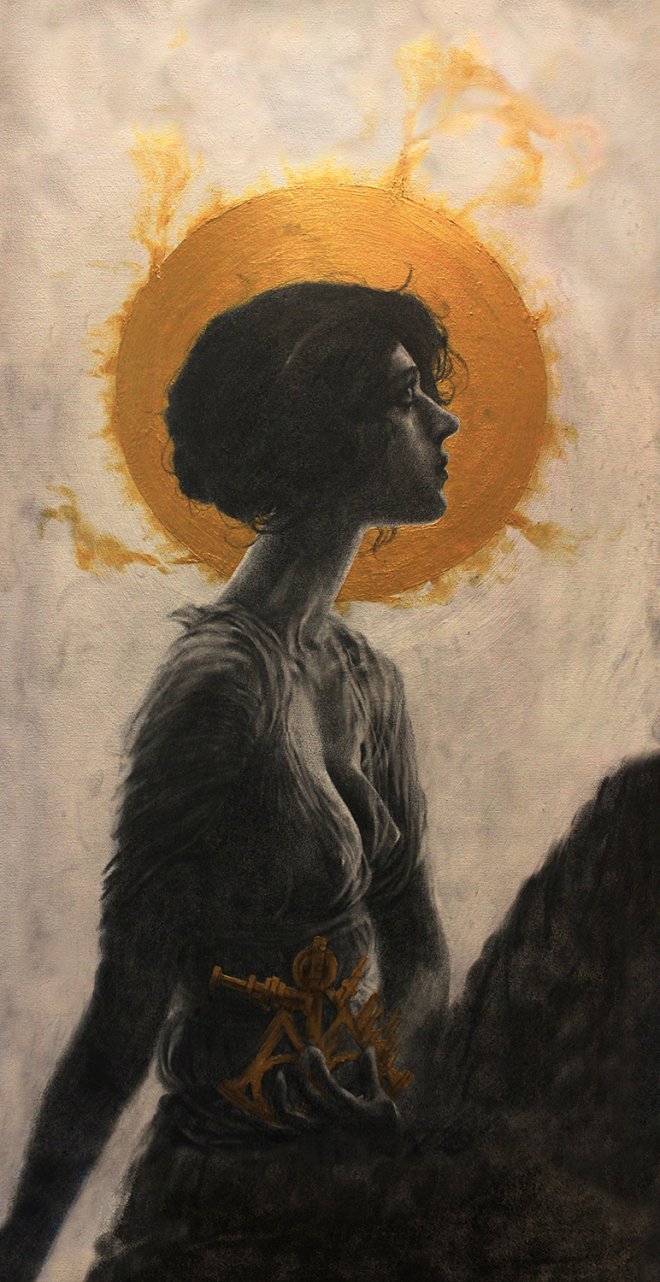

On the streets of Alexandria a mob of Christian zealots led by Peter the Lector apprehended a woman as she boarded her chariot—having only finished the days lecture at the University—and dragged her into a nearby church, where they stripped her naked and barbarically murdered her with roofing tiles. Though parts of her flesh were reportedly scattered across the city, the rest was burned. Her name was Hypatia. She was described by her students as exceptionally exquisite to behold. Men gazed from afar. The year was 414, and at the time of her death—being perhaps sixty years-mature—she was Egypt’s trophy intellectual. Hypatia’s crime, they say, she clung to occultism in a generation when Christianity sought to purge Luciferian doctrine from its Empire. If it is true, that the murder of Hypatia swept humanity into the medieval cauldron, then it is hardly a stretch of fantasy to imagine that it was her very ghost, once excavated, which certified our arrival into this modern age of Science. Hypatia had enemies. And one day she’d return to haunt them all.

“They could not argue with her, so they murdered her.”

The Roman Empire may have once ruled the known world, but by the end of the fourth century it was apparent that the world had grown far too large for one central government to manage. And so in 395—almost a century after the edict of Milan (which legalized Christianity under Emperor Constantine)—the Empire itself was historically split in two. Hypatia was roughly 40 years young at the time, and though Rome would continue its management of Western Europe for the remainder of her life, she and the rest of Alexandria suddenly found themselves under the sanction of Constantinople.

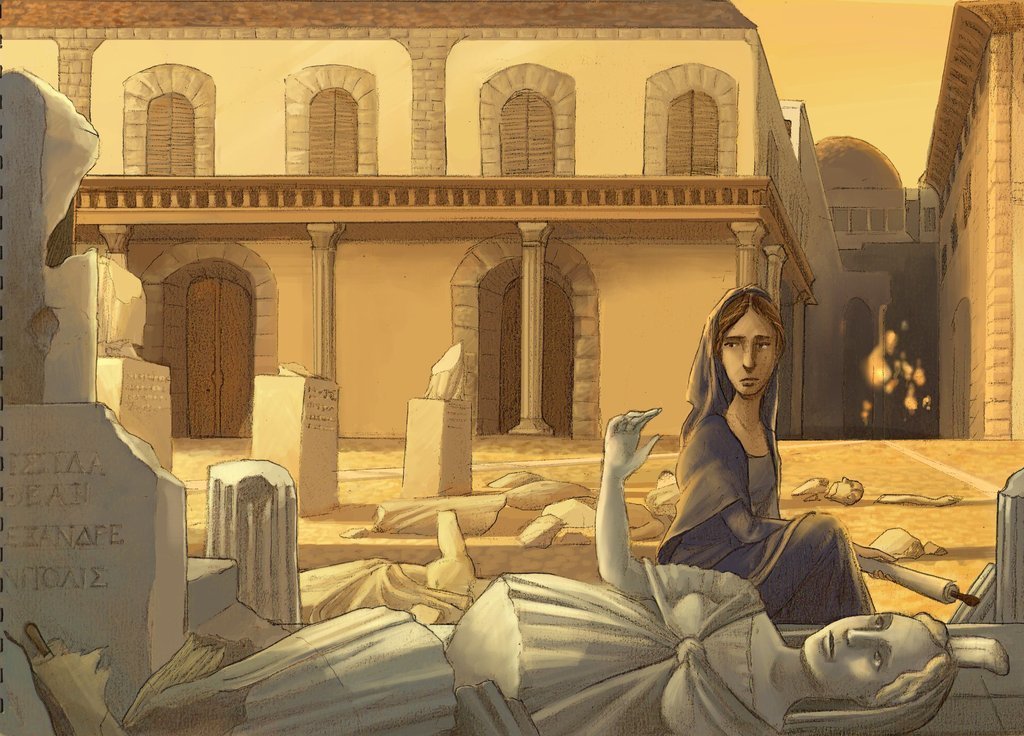

Founded by Alexander the Great some 750 years earlier—in 331 BC to be exact—the city soon swelled into a metropolis of Occult Sciences. At its heart was the Museum. An estimated collection of some 700,000 scrolls were housed at one time in its library. The Alexandria of Hypatia’s day may not have been a seat of power, as was Rome or Constantinople, but it remained the heart of the ancient world; a hotbed of intellectual activity, with the roots of Paganism and the exploding Gospel of Jesus Christ acting as competing rivals for the salvation—depending on who you spoke to—of the soul and mind. As such, Alexandria was the last refuge of humanism. If the dark ages dawned in Alexandria, then so too would the entire ancient world darken.

There was a time before Emperor Constantine when Occult Science embellished Rome with its muscular physique, even supplying the very air it breathed. Hypatia did not live under this umbrella. With Emperor Theodosius I, last to rule over both the eastern and western halves of the Roman Empire, the ancient Mystery Schools perished. Few were strong enough to resist his hand. A decree promulgated in 391 that “no one is to go to the sanctuaries, or walk through the temples” resulted in the abandonment of many pagan institutions throughout the Empire. The Roman state gave free reign to Christian extremists to destroy pagan shrines and commit violence against its priests. Arson was a favorite tactic. Monks stand out as primary aggressors.

Some were not above murder.

The pagan Eunapius remarked that these monks looked like men but behaved as pigs, “and openly did and allowed countless unspeakable crimes.” He added bitterly, “For among them, every man is given the power of a tyrant who has a black robe and is prepared to behave badly in public.” In 396 Christian monks—the Occultists referred to them as “black shirts”—led Visigoth barbarians towards the School of the Eleusinian Mysteries near Athens. It too was decimated. The Sanctuary of Eleusis, one of the grandest buildings in the ancient world (the outer courts of which could reportedly hold 300,000 worshipers) was reduced to ruins—another striking blow to the Occult. So too did Theodosius I turn his thoughts upon Alexandria.

Starting in 390 the Emperor had the obelisk of Pharaoh Thutmose III transported from Alexandria to Constantinople. Though the Museum had already been under the control of Catholic priests since the time of Constantine, the vast group of buildings known as the Serpeum remained within the clutches of Paganism. So too was the Temple of Serapis—employed now as a University—and the Library of the Serapion still housed a vast collection of books. It was at the University where Hypatia taught the “old religions and sciences.” Here the Mysteries as a public institution would make their final stand.

Bishops were called to exercise the immense powers conferred upon them by the Emperor. Charges of political corruption, ill-will, evil-nature, and irreverent abuse of their leadership are overwhelming against Theodosius I and the church leaders of that generation. As the Archbishop of Alexandria, Theophilus was no exception. The English historian Edward Gibbon has labeled him “the perpetual enemy of peace and virtue; a bold, bad man whose hands were alternately polluted with gold and with blood.” Colorful descriptions within modern scholarship continue to bedevil him. He is said to have “bribed the slaves of the Serapion to steal some of the books, which he sold to foreigners at exorbitant prices.” Theophilus went to work confiscating abandoned Temples and restructuring them into churches. Naturally, Pagans objected to the desecration of their sacred places and symbols. Riots ensued. The philosopher Olympus, a contemporary of Hypatia, attempted to defend the Temple of Serapis. Under orders of Emperor Theodosius, men “sacked the Temple, broke the statue of Serapis in pieces, dragged it ignominiously through the streets of the city, and finally burned it.” The year was 398. When a Christian Church was later erected upon its ruins, the “martyrs” who had suffered in the riot were honored there.

So too was the Serapion Library eliminated from use. While some historians frame its destruction against a long-term backdrop of frequent mob violence in the city, particularly a four-hundred year conflict between the Greeks and Jews who inhabited those quarters, most agree its final demise came with the Christians rejection of Paganism. Only the Neoplatonic School remained.

Hypatia’s father Theon was the last man whose name is recorded as a professor at the Alexandrian Museum—though she herself sat in the chair of philosophy, and throughout the city she wore the cloak of the Philosopher. Though an astronomer and mathematician, Theon was devoted to divination, astrology, and the Mysteries. He wrote a commentary on Ptolemy’s Syntaxis, and acknowledged his daughter in its composition. Suidas claims Hypatia wrote commentaries on Diophantus, on the Astronomical Canon of Ptolemy, and on the Conics of Apollonius of Perga. Like most of Alexandria’s once-rich literary collection, none now survive. He furthermore penned commentaries on the books of Orpheus and Hermes Trismegistus and poems relegating the planets as forces of Moira—destiny. Nothing indicates that Hypatia departed from her upbringing. In actuality, Hypatia carried them further. The Chaldean Oracles and Pythagorean numerological mysticism figured in her teachings, as the letters of Synesius indicate. Like her father, she saw astronomy as the highest science, opening up knowledge of the divine.

Hypatia’s father Theon was the last man whose name is recorded as a professor at the Alexandrian Museum—though she herself sat in the chair of philosophy, and throughout the city she wore the cloak of the Philosopher. Though an astronomer and mathematician, Theon was devoted to divination, astrology, and the Mysteries. He wrote a commentary on Ptolemy’s Syntaxis, and acknowledged his daughter in its composition. Suidas claims Hypatia wrote commentaries on Diophantus, on the Astronomical Canon of Ptolemy, and on the Conics of Apollonius of Perga. Like most of Alexandria’s once-rich literary collection, none now survive. He furthermore penned commentaries on the books of Orpheus and Hermes Trismegistus and poems relegating the planets as forces of Moira—destiny. Nothing indicates that Hypatia departed from her upbringing. In actuality, Hypatia carried them further. The Chaldean Oracles and Pythagorean numerological mysticism figured in her teachings, as the letters of Synesius indicate. Like her father, she saw astronomy as the highest science, opening up knowledge of the divine.

Of the little that is known about Hypatia—biographically speaking—the following account by Socrates Scholasticus, which was completed sometime in the decade before the death of Theodosius II in AD 450, is the best and most substantial. Socrates wrote:

“There was a woman at Alexandria named Hypatia, daughter of the philosopher Theon, who made such attainments in literature and science, as to far surpass all the philosophers of her own time. Having succeeded to the school of Plato and Plotinus, she explained the principles of philosophy to her auditors, many of whom came from a distance to receive her instructions. On account of the self-possession and ease of manner, which she had acquired in consequence of the cultivation of her mind, she not infrequently appeared in public in presence of the magistrates. Neither did she feel abashed in coming to an assembly of men. For all men on account of her extraordinary dignity and virtue admired her the more.”

As a devoted Neoplatonist Hypatia never married—despite the astonishing beauty which cast men’s gaze from afar. Plato’s suggestion in The Republic to abolish the family-unit in favor of Government-accredited “Guardians” derived from a desire to create the Utopian society. In such a world inequitable ownership of private property no longer exists. This dream—more precisely, nightmarish reality—persists even today at the UN. In Hypatia’s own words, she justified her non-commitment to any one man—her virginity is likely a mystical metaphor, by the way—as “already being married with the truth…” According to the Greek historian Damascius, two different and potential responses were delivered after one of Hypatia’s students professed his unreserved love for her. The more polite version, which he sighs as the less likely, is that she told him that music was the antidote for love. The less polite version is that she handed him a bloody menstrual rag and said “this is what you really love—my young man but you do not love beauty for its own sake.” How Platonic of her.

The March 1937 edition of THOSOPHY states: “The Neoplatonic School reached its greatest heights in the days that immediately preceded its destruction. Hypatia brought Egypt nearer to an understanding of its ancient Mysteries than it had been for thousands of years. Her knowledge of Theurgy restored the practical value of the Mysteries and completed the work commenced by Iamblichus over a hundred years before.”

With theurgy—a system of white magic practiced by the early Neoplatonists—its practitioner could reach God through spiritual magic and ascend up the scale of creation through rigorous prayer, fasting, and devotional preparation, particularly with the goal of achieving henosis (uniting with the divine) and perfecting oneself. According to A. Wilder, “the problem of life is man. Magic—or rather Wisdom—is the evolved knowledge of the potencies of man’s interior being…” Pierre A. Riffard, a French philosopher and esoterists, says of the practice: “Theurgy is a type of magic. It consists of a set of magical practices performed to evoke beneficent spirits in order to see them or know them or in order to influence them, for instance by forcing them to animate a statue, to inhabit a human being (such as a medium), or to disclose mysteries.”

THOSOPHY further adds:

“Following in the footsteps of Plotinus and Porphyry, she demonstrated the possibility of the union of the individual Self with the SELF of all. Continuing the work of Ammonius Saccas, she showed the similarity between all religions and the identity of their source.”

Occultist Manley P. Hall holds Hypatia in the highest regard. Alexandria’s trophy intellectual “eclipsed in argument and public esteem every proponent of the Christian doctrines in Northern Egypt.” As part of her Neoplatonic School curriculum, Hypatia employed the inductive method of reasoning first sponsored by Aristotle to pull the rug out from under the foundations of Christian dogma. She was so well versed in the accumulated belief systems of ancient times, it is said that one of her books was about a “compendium of comparative religion,” and may have resembled something of Hall’s very own The Secret Teachings of All Ages. She further mocked the religion of Christ by openly exposing metaphysical allegories from which Christianity had borrowed its dogmas. According to Hall, “Hypatia not only proved conclusively the pagan origin of the Christian faith but also exposed the purported miracles then advanced by the Christians as tokens of divine preference by demonstrating the natural laws controlling the phenomena.”

Hypatia sought to dispel the belief that the doctrines of Plato and Plotinus and the Mysteries from whence their philosophies had arisen were in any way dangerous. She was particularly gifted—by way of reasoning—at turning the tables on the Church of Rome. Now the ancient Mysteries would be flung into the open and, by treating the old Pagan view and Christianity as one and the same, Jesus would be treated as pagan and esoteric. In other words, what was the sin in peering into the ancient Mysteries, which was not only built upon the Serpents damnable promise to Eve in the garden, but expounded on his lie?

“A number of writers,” Hall adds, “have credited the teachings of Hypatia with being Christian in spirit.” Perhaps because she attempted to bleed Platonism and the teachings of Christ together into one ecumenical stewpot, and in fact, many new converts to the Christian faith deserted their first love to become one of her disciples.

One such convert from Christianity to Occult Science, perchance Hypatia’s most adoring pupil, was Synesius of Cyrene—a bishop ironically consecrated by Theophilus himself. Seven letters addressed to Hypatia still survive, though he refers to her in several more. He laments not hearing from her, for she is “the only good thing that remains inviolate, along with virtue. You always have power,” he writes, “and long may you have it and make a good use of that power.” About the time of his death (a year or two before her own), he dictated a letter calling her “mother, sister, teacher, and withal benefactress, and whatsoever is honored in name and deed.” She is the one “who legitimately presides over the mysteries of philosophy” and “my most revered teacher.” More than just a philosopher, mathematician, astronomer, and scientist, Hypatia was clearly regarded in the light of a spiritual leader. For Synesius the Cyrene, she was “the most holy and revered philosopher,” “a blessed lady,” and “divine spirit” with “oracular utterances.” His teacher, Synesius contemplated, was “beloved by the gods.”

Despite these confessional heresies, many modern historians paint Synesius in the light of a persistent Christian—too academic perhaps for his unintelligible contemporaries—and yet because of her influences he obstinately held to the Platonic belief in an eternity of the cosmos and worse, the Luciferian divinity of the soul which—unlike the Judeo-Christian insistence in an unsustainable existence apart from the flesh, returning to dust due to sin and demanding physical resurrection—stressed a separate but distinct and sustainable substance, eternally speaking.

Essentially, Orthodox Christians in Alexandria were abandoning their faith to follow Hypatia’s esoteric branding—which the Gnostics were already succeeding at anyhow. Egypt had a way of perverting true religion. In a broader picture, Synesius and his brethren, though perhaps clinging to a Christian title, were in direct conflict with the Cappadocian Fathers—Basil the Great (330–379), who was bishop of Caesarea; Basil’s younger brother Gregory of Nyssa (335–395), who was bishop of Nyssa; and a close friend, Gregory of Nazianzus (329–389), who became Patriarch of Constantinople.

In Synesius of Cyrene, Philosopher-bishop, Jay Bregman writes: “The Cappadocians’ approach was diametrically opposed to Synesius’. They believed the Scriptures, not philosophy or the Platonized Chaldean Oracles, were the Gnosis and Christian Oracles (logia) of God. This Gnosis is in the Old and New Testaments. They were revealed by the Holy Spirit through the theologoi or mouthpieces of God. For Synesius there were also a few autodidacts instructed by God, but these were to be found in all religious traditions. As a syncretist, Synesius had no trouble including Zoroaster and other pagan and Christian figures.”

Surviving fragments of letters and affectionate correspondences indicate a mystical orientation. Glimpses of her spiritual views describe and assign “the eye buried within us” as a “divine guide.” Furthermore, as the soul journeys toward divinity, this “hidden spark which loves to conceal itself” grows into a flame of knowing. True to her theurgy tutelage under the Aristotelian philosopher and magician, Plutarch of Athens, Hypatia’s philosophy circumnavigated the “mystery of being,” an elevator approach to consciousness, and “union with the divine,” or the One.

Surviving fragments of letters and affectionate correspondences indicate a mystical orientation. Glimpses of her spiritual views describe and assign “the eye buried within us” as a “divine guide.” Furthermore, as the soul journeys toward divinity, this “hidden spark which loves to conceal itself” grows into a flame of knowing. True to her theurgy tutelage under the Aristotelian philosopher and magician, Plutarch of Athens, Hypatia’s philosophy circumnavigated the “mystery of being,” an elevator approach to consciousness, and “union with the divine,” or the One.

Truly, Hypatia was adored by many, “but the admiration was not quite universal,” writes Will Durant in The Age of Faith: The Story of Civilization. “The Christians of Alexandria must have looked upon her askance, for she was not only a seductive unbeliever, but an intimate friend of Orestes, the pagan perfect of the city.” Alexandria was a populace, says Socrates, which “is more delighted with tumult than any other people: and if at any time it should find a pretext, breaks forth into the most intolerable excesses; for it never ceases from its turbulence without bloodshed.”

In 412, Cyril, the nephew of Theophilus, succeeded him as patriarch of Alexandria. Upon taking his uncle’s place, Cyril needed his own conquest against paganism. In time, he would set his gaze upon Hypatia. Orestes resisted ecclesiastical encroachment upon his civil jurisdiction. The two clashed. Meanwhile, riots between Christians and Jews persisted. After a brawl in the theater, the Perfect had one of Cyril’s followers arrested and tortured. When Christians were killed in yet another riot, the archbishop led a mob which resulted in the expulsion of Jews from Alexandra. Even their possessions were looted. No sooner had Orestes objected when he himself was assaulted by monks “of a very fiery disposition.” One such assailant was tortured to death. Cyril made a martyr of him.

The 7th-century Egyptian Coptic bishop John of Nikiu, who served as a general administrator of Egypt’s upper monasteries around 696, chronicled a historical narrative which extended from Adam to the end of the Muslim conquest in Egypt. He described Hypatia as a pagan philosopher “devoted at all times to magic, astrolabes and instruments of music” who “beguiled many people through Satanic wiles.” Orestes, the Imperial Perfect of Egypt and Alexandria’s governor: “honored her exceedingly, for she had beguiled him through her magic.”

Prefect Orestes enjoyed the political backing of Hypatia. Though an Occultist in an ever-widening Christian Empire, her political influence cannot be denied. Indeed, many students from wealthy and influential families came to Alexandria, purposely forsaking the newly endorsed religion of the land to study privately with Hypatia, and many of these later, quite ironically, attained high posts in government and the Church. Not only would the Imperial Perfects customary church attendance cease, “but he drew many believers to her…” Cyril’s supporters charged Hypatia with being Orestes’ chief instigator, “for as she had frequent interviews with Orestes, it was calumniously reported among the Christian populace,” wrote Socrates, “that it was she who prevented Orestes from being reconciled to the bishop.” The Christians of Alexandria had no weapon against her—none but violence.

“She was torn to pieces by a mob of incensed Christians not because she was a woman,” wrote Iain Pears in The Dream of Scipio, “but because her learning was so profound, her skill at dialectic so extensive that she reduced all who queried her to embarrassed silence. They could not argue with her, so they murdered her.” It should be noted that the Neoplatonist historian Damascius, likely sympathetic of Hypatia’s Occultism, was “anxious to exploit the scandal” that was her death. His account is the sole historical source attributing direct responsibility to Bishop Cyril. The church of Rome insists he had nothing to do with it.

Despite the scattering abroad—and ultimate survival—of neoplatonists, Saint Cyril of Alexandria held onto few friends, even in the church. Nestorian bishops at the Council of Ephesus declared the man who became a saint a heretic, labeling him a “monster, born and educated for the destruction of the church.” The Bishop Theodoret of Cyrus wrote to Domnus, Bishop of Antioch, after learning of Cyril’s death: “At last and with difficulty the villain has gone. The good and the gentle pass away all too soon; the bad prolong their life for years…”

While Cyril’s direct involvement in Peter’s lynching of Hypatia is still debated to this day, it is clear that no punishment was exacted on anyone. It was “an act so inhuman,” recalled Socrates, and yet “this affair brought not the least opprobrium, not only upon Cyril but also upon the whole Alexandrian church. And nothing can be further from the spirit of Christianity than the allowance of massacres, fights, and transactions of that sort.” Emperor Theodosius II merely restricted the freedom of the monks to appear in public, and excluded pagans from all public office. Cyril had managed the tightrope balancing act of his uncles legacy. As a public institution, the Mysteries were no more. Together, their victory was complete. “All the people surrounded the patriarch Cyril and named him ‘the new Theophilus’,” wrote John of Niku, “for he had destroyed the last remains of idolatry in the city.”

Very few will remember Cyril as being the man responsible for promoting Mary from the Mother of Jesus to the “Mother of God,” and even less know he introduced the image of Isis—pictured nursing the infant Horus at her breast—into the Christian Church under the guise of Mary. Here in America the eye of Horus is printed upon our one dollar bill. We even have an obelisk erected to him in Washington D.C. For the Occult, which is healthier now than it was in Hypatia’s generation, Horus is cleverly hidden with the Lady Madonna and double-downs as the coming anti-Christ. Oddly enough—and perhaps there is a piece of the puzzle missing here, where the archbishop and Hypatia’s ambitions come together… and conflict—Saint Cyril helped integrate into the Catholic Church the very hieroglyphic penmanship which he himself was publicly suppressing. When Christianity overthrew Rome, many clergymen simply exchanged one cloak for another and remained within the same breach of mysticism.

There is a reason why God said regarding Egypt: “Ye shall henceforth return no more that way (Deuteronomy 17:16).” Egypt had a way of perverting true religion. Here before us is a case study. In the outer-rim of the Christian Byzantine Empire, the Occult—albeit Occult Science—was infiltrating, compromising, and perverting the truth. “And then you can cast her story—as generations of allegorists, from Voltaire to Gibbon to Charles Kingsley have done,” writes an embittered Harvard University Press; “as a battle between the waning light of the ancient pagan world, with its amassed wisdom, and the encroaching darkness of Christian dogmatism.”

So we commence with the dawn of the dark ages. It is a marathon length funeral procession which the Theosophists, the Occultists, and members of secret societies have long-since agonized over. Freemason Albert Pike would resort to name-calling, specifically the “dunces who led primitive Christianity astray” and “succeeded in shrouding in darkness the ancient discoveries of the human mind—so that we now grope in the dark to find again the key of the phenomena of nature…..” The details of Hypatia’s so-called brilliance would die with her, for the most part—though some delectable thoughts remained. And while the Mysteries which she championed would trudge on among the goop of crypts and catacombs, it would not, as history has proven, slither among the snakes and the roaches forever. Clergymen have a way of exchanging one cloak for another.

Nicolaus Copernicus, it seems, was there for the momentous occasion. Before his new conception of the universe was published posthumously in 1543, Copernicus was but a pupil under Domenico Maria de Novara, an astronomy professor in Bologna. While in Florence, it is extremely likely that Copernicus read the Almagest, complete with Theon and his daughter Hypatia’s comments scribbled within; given that the only copy of Ptolemy’s work was in the Medici library of that city, a library which Copernicus visited for his research. Hypatia never accepted the Earth-centered model. Her notes in Ptolemy’s Almagest prove that she clearly rejected the geocentric Ptolemaic theory in favor of the heliocentric model. Copernicus was enthralled by the thought of it. Possessed even.

The Mystery Religion struck back.

Copernicus, Meet Hypatia. Queen of the Occult. Mother of Heliocentricism.

Hypatia once said: “All formal dogmatic religions are fallacious and must never be accepted by self-respecting persons as final.” Indeed, the ghost of Hypatia was exhumed in Florence, Italy. By overturning the cosmological-belief of a sacred Word which had overseen her own undoing, the Copernican Revolution was the perfect revenge.

“Fables should be taught as fables, myths as myths, and miracles as poetic fantasies. To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing. The child mind accepts and believes them, and only through great pain and perhaps tragedy can he be in after years relieved of them”—Hypatia

Noel