The Challenger Explosion was a Psychodrama

1

SEVERAL CONSIDERATIONS ARE PROBABLY in order as to why I distinctly recall the space shuttle Challenger disaster in real time—specifically the manner in which its memory has always been recollected. It’s literally burned into my mind. On the 28th of January, 1986 I was only five years old, and wouldn’t even graduate from kindergarten until the following year. So what was I doing at a school I wasn’t technically allowed to attend until September? I don’t have an easy answer for that.

Here’s another complication.

The Challenger shuttle exploded over Cape Canaveral at precisely 11:39 in the morning, Eastern Standard Time. In Hawthorne, California, three hours earlier, school wouldn’t even begin until nine. And yet there I was, sitting in the very library where I would complete the eighties pouring through the “P” lettered encyclopedia in my spare time to dream uneasily about Blackbeard and his army of pirates, or hang gliding over a mooing paraceratherium, the world’s largest ever existing mammal, while a saber-toothed cat growl at a sad looking woolly mammoth trapped in tar, none of which begin with “p” per say, except for the fact that I could probably find an illustration of them while reading about prehistoric times. Occasionally I might even flip through “T,” always on a trembling search for tornadoes—“A” for astronaut or “S” for space, not so much.

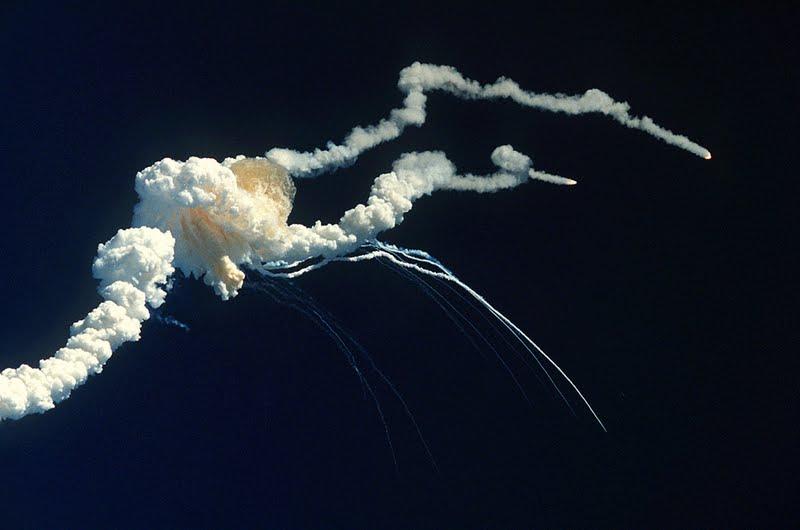

I do not remember what I had for breakfast that morning, or even if I attended preschool, about a mile down Inglewood Ave., later that day. My only conclusion is that CBC was a private school on Centinela Bible Church property, and my father was pastor. A visit was not uncommon. In fact, the back yard of our parsonage doubled as the school’s playground. If I were home sick, I could simply stand up in bed and cup all ten fingers to the window in order to watch my classmates play. Perhaps, and this is another fair guess, because a teacher was involved in the shuttle’s launch, I was simply invited to watch. The media, the entire schooling system, in fact all of America made a big deal of it. An estimated 17 percent of American’s witnessed Challenger’s demise on live television. 85 percent would hear of it within the hour. But one thing I am quite certain of. The church library is where I watched the Challenger shuttle get rocketed up—up—up within the box-shaped television screen, a clunky device which, when married to its gray roller, could scurry around from room to room on a whim—bulking knobs for channels. To a five year old, its 73 second flight seemed like an eternity.

And then it exploded.

Even now I can close my eyes and hear the droll, almost colorless, though collected voice of the television reporter, maybe even backed by a NASA control man, as the unexpected flames disrupt the ceremony. Oh my god. I can contrast that with a total gaping silence in the room. Gene Mac Andrews, the school’s principal, still hastily turns off the television, every time I rewind and replay the tape in my head—soon as he realizes what is happening—and promptly instructs everyone to return to class, or perhaps start class. Either way, I don’t rightly recall. If he ever gets around to talking about what they’ve seen, and most assuredly how they are expected to process the experience, I have no memory of it. Nothing that happens before or afterwards remains on the tape reel in my skull, undoubtedly because I didn’t yet attend the school. Somebody took me there to view the shuttle launch, and perhaps that same someone escorted me out. I simply don’t know. Back to Go, Dog Go and Green Eggs and Ham, tricycles and stacking blocks. What I witnessed there on that January morning was never spoken about again.

2

MY ENTIRE POINT IS THIS. A MAN is purposed to live thousands of ordinary days in his lifetime. It is only once every decade or two in which those thousands of inconspicuous moments become cause for a collective, even ceremonious consciousness. The two massive explosions which blew open a 1,000 ton roof from the Chernobyl power plant in Ukraine, releasing 400 times more radiation than the atomic bomb reportedly dropped on Hiroshima wouldn’t happen for precisely another three months—April 26, 1986. And yet I would imagine that I’d have a difficult time finding someone who could tell me where they were or what they were doing when news of that defining Reagan-era event happened.

On the 28th of January, 1986, Rick Hummer chose the most ordinary day imaginable to skip school. His decision would become part of the ceremony. “I wasn’t feeling that great,” he halfheartedly maintains, though admittedly, he did dial up the symptoms just a tad—a notch above smidgen, in order to secure a day home from school. His mother bought the padded groan. One only needs wonder if his mother had backed down the full length of the driveway before the television was turned on. At any rate, within moments of her departure, and with the house to himself, he was already bored. For whatever reason, Hummer decided to dig into his closet.

Maybe it really needed cleaning out. Then again, we must not overrule a simple and straightforward, if not totally probably, case of boredom.

I am a firm believer that coincidence is simply the residue of design. It was there in that closet that he stumbled upon a crinkled up picture of the Challenger shuttle. His older sister had married a police officer, who was stationed at Edwards Air Force Base in the Mojave desert, just north of Lancaster—Charles Johnson’s backyard. In turn, his brother-in-law snapped the photo “when they were doing the test runs—when they were landing it at Edward’s Air Force Base It was the one that they had piggy-back on a jet.” He ironed it out a little. “I was mad that that picture got messed up.”

And then it occurred to him.

Wait—wasn’t the Challenger supposed to launch today?

In fact, that very moment, the television in the other room (which, mind you, likely turned on the moment after his mother left for work) seemed to speak directly at him.

CHALLENGER.

The CHALLENGER will launch today.

Cape Canaveral, CHALLENGER.

CHALLENGER.

Teacher, 10, TEACHER, 9, teacher, 8…

Get in here, Rick Hummer.

Now, 7…

CHALLENGER.

Riiiiiiicck….

In an unprecedented stay-home-from-school move, Hummer made a b-line dash for the living room, feeling miraculously better, mind you, and plopped down onto the couch in order to catch what had already been promised to be the lift-off of the decade.

“Obviously we all know what happened,” Hummer said. “We were all told that this thing exploded when it exploded, and I had the most eerie feeling being there at home by myself, even though I was in the eighth grade, I was still empty when I saw that, and what they were saying on TV, and I kept thinking about those people free-falling back to earth…. if they were alive. What would it be like when they hit the water? There was no way they were going to survive.” Why didn’t they have parachutes in the cockpit? “All this stuff was going through my head. I didn’t want to be home alone anymore. I felt awful.”

Hummer jumped on his bike to brave the frigid cold of January along the shores of Lake Michigan. His rode all the way to Mr. Kaufman’s office—his school principal.

“I don’t know if you guys have done this yet,” Hummer told him, likely out of breath (but what thirteen or fourteen year-old loses his breath for long?), “but I think we ought to have a moment of silence, for the crew and their families, before we leave today.”

Mr. Kaufman stared at the pink-faced teenager standing before him in awe. “You know, you’re absolutely right.”

Hummer said, “And so I ended up going to class, and it was a very somber thing, because everybody had watched it—everybody was talking about it.” There was of course the occasional kid cracking jokes, “as kids can be, but what I remember about it is that it really bothered me, because at that age I was already thinking about going into the air force. I was already thinking about what it would be like to go to space someday. I really wanted to be a part of the space program when I was a kid.”

Meanwhile, in Sacramento, California, seventh grader Shelley Lewis witnessed the immediate unrestrained tears of her science teacher.

Christa McAuliffe was a teacher.

She was supposed to be the first teacher in space.

“The whole school declared a day of mourning,” she said. “Everybody remembers where they were. Just like 9/11, when those planes hit—everybody has that memory.” In a way, the Challenger shuttle disaster became a personal acclamation. “It became this thing of, well—we don’t know what’s going to happen to the space program.” But Lewis very much wanted to be part of the space program.

Uh, Hummer thought, I don’t know if I want to do this anymore.

The space program kind of looks… dangerous.

Shelley Lewis however would risk it. She put everything on the line. It would take thirty accumulating years before shuttle Challenger became another sort of rallying cry altogether. What happened on the 28th of January, Lewis now concludes, “is the basis of mind control.” Psychodrama. “Kind of like the World Trade Center falling down, everybody was watching. It’s a way to crate fear and sadness and sorrow. When you create a traumatic event, you instantly remember everything about that day—where you were, who you were with. You just have that recollection of things, and you never forget it. And that was a part of MK Ultra—trauma-based mind control.”

In a special issue of Flat Earth News, Charles Johnson maintained that the shuttle Challenger had either been exploded by NASA or had fallen victim to a divine curse. Not one for mincing his words, his headline read: ‘Challenger Blown up by God.’ If Johnson had the sort of research sophistication to know what the MK Ultra program truly was, he only seemed to let it out in doses. For example, Johnson asserted that astronauts are either force-fed drugs or either brainwashed into believing the round “Earth and planets nonsense.” Once, to a San Francisco Examiner reporter, Johnson marveled, “Some astronauts actually believe they’ve been in space.” The greatest sensation of that day however is the fact that President Ronald Reagan, while giving televised interviews about the shuttle disaster, mentioned God and then looked up to the sky. Johnson was jubilant. The very gesture, he said, derives from a starting point (if even subconsciously), whereas heaven is above the earth, and the earth is flat.

It is rather ironic, nearly three decades later, that the teacher who hitched a ride into space would be claimed alive. “We know now,” Hummer said, “obviously, there’s a very good chance that some of those folks are still alive and well, some under the same names, and still using the same names—as far as I can tell.”

If only Johnson had lived long enough to hear of it.

Not that Payload Specialist McAuliffe was given a parachute and a life raft or anything. In what will assuredly come across as a plot twist to yet another Twilight Zone episode, of Challenger’s tenth mission line-up, which included Commander Francis R. Scobree, Pilot Michael J. Smith, Mission Specialists Ronald McNair, Ellison Onizuka, Judith Resnik, and Gregory Jarvis, several would furthermore be claimed as those who might be counted among the living, with pictures to prove it. They were never on board to begin with. But here’s the ultimate plot twist.

Nowadays, they’re all teachers.

Noel

JOIN OUR NEWSLETTER!

Stay up to date on the latest articles and news from Noel.