Flight of the Navigator: Johannes Kepler’s Journey to the Dark Side of the Moon

ON THE EVENING of July 4, 1978, a twelve-year-old boy named David Freeman is sent by his parents to retrieve his annoying younger brother from a friend’s house. The scene if Fort Lauderdale, Florida. Night approaches. His dog tags along.

David crosses the train tracks and then proceeds through a wooded grove—a journey he’s no doubt responsibly managed on countless other occasions. His brother appears out of nowhere and then stays in character by obnoxiously running off. Something quickly grabs his dog’s attention in a ravine below. The boy peers over the edge.

He stumbles in.

When David comes to consciousness, he dusts himself off and then returns home by the same route, without his dog (his brother is presumably a lost cause), only to find that an elderly couple occupy the house which had, seemingly moments earlier, belonged to his family.

His nightmare is strengthened by the fact that Jimmy Carter is no longer president of the United States. And though his parents had searched for his whereabouts in vain, David Freeman must contend with the fact that he was legally declared dead. Actually, if the police report is to be believed, an entire eight years have passed since the fateful night when he fell into the ravine.

The year is 1986. And he hasn’t aged a single day.

The movie in question is Flight of the Navigator, and it is here that the story takes yet another interesting turn. A test at the hospital reveals images of the spaceship which NASA has only recently captured imprinted in David Freeman’s brainwaves. He is quickly hurried to NASA’s research facility, presumably Kennedy Space Center, where a man by the name of Dr. Faraday learns that the boy was in actuality whisked to a distant planet called Phaelon, 560 light years away from Earth. Apparently, Einsteinian equations come into play because, though the roundtrip journey exhausted only 4.4 hours of his own life, an entire eight Earth years has otherwise waxed away. But we know that little detail already. The greater discovery however results with the extraterrestrial technical manuals and star charts, covering expanses of the galaxy far exceeding NASA’s own research, which are currently stored in the ninety-percent of David’s unused mind.

Though some will insist it is only a movie, the screenplay, written by Michael Burton and Matt MacManus, based upon a story by Mark H. Baker, would not be the first time that astronomers received textbook knowledge of the Copernican Universe through the intervention of its hidden inhabitants.

A DOCTRINE OF DEMONS

AT THE TURN OF THE 17TH CENTURY the Reformation was still waging its theological war over the will of the humanist mind in every corner of Europe, and Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), a German mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, and alchemist, chose his side. He aligned himself with what he aptly christened ‘New Astronomy.’ It was a position that openly opposed the firm foundation by which men like Tyndale, Melanchthon, Knox, Zwingli, and Luther, and anyone else who proclaimed the principles of Scripture Alone, stood upon. Kepler was no stranger to theology either. Both sides of the feud held hands with Biblical doctrine, or in the very least some form of it—selectively. And yet Kepler, along with his contemporaries, believed the MOST-HIGH had created the world according to an intelligible plan which could not be accessed through a reading of His Word, but only through the natural light of human reason.

|

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) |

Kepler described his Copernican-based ‘New Astronomy’ as “celestial physics,” being “an excursion into Aristotle’s Metaphysics,” and “a supplement to Aristotle’s On the Heavens.” The recovery of Aristotle into Latin texts from its Greek and Arabic counterparts no doubt fueled the Big Bang explosion of humanism in the Enlightenment church, despite the Reformers’ best efforts, and is conclusively a radical departure from the teachings of early Christianity. It is somewhat strange that the first serious treatise on lunar astronomy, as told in Kepler’s 1608 novel Somnium (Latin for The Dream), and only published by his son after his death, also happened to be what Carl Sagan referred to as the first real work of science-fiction. Then again, the truth is stranger than fiction. Somnium gives dark insight inside the mind of a man who gifted the world with “Kepler’s Laws of Planetary Motion,” works which would later provide one of the foundations for Isaac Newton’s theory of universal gravitation. In short, according to Kepler’s novel, knowledge of the Universe, particularly its scope and motion, came not to us from the observant eye of an astronomer pressed firmly against his telescope, but through communion with demons.

The story, which centers around Kepler’s own dream about himself reading a book, involves Duracotus, a fourteen-year-old Icelandic boy with a witch for a mother, who makes a living selling bags of herbs and cloth with strange markings on them. This, after Kepler first reads from another book about Libussa, a historical sorceress and prophetess in her own time, before falling asleep—and who may have evoked the story within the dream. On a side note, her habit of summoning demons—the boy’s mother, that is—comes well rewarded. She has learned all she knows about astronomy from them, even knowledge concerning great unobservant distances. It is the demons, we come to learn, who not only help their human counterparts travel around the world, but (through their own technological sorcery) to the moon and back.

The moon is of particular interest to the boy and his mother. So, upon summoning her favorite demon, they are told in elaborate detail about Levania, its demon-given name. Apparently, Levania is an island in the Aether, and is further divided into two hemispheres, Privolva and Subvolva. Privolva, or the dark side of the moon, never has visual contact with the earth, but planets appear bigger. The residents of Subvolva on the other hand, oddly mirroring Einstein’s own up-and-coming theory of relativity, can observe the rotation of Earth without ever feeling any movement themselves.

As it turns out, there’s a pathway between Levania and the Earth which, when opened, some humans are said to have traveled, so long as the demons are there to escort them. The journey, spanning fifty-thousand miles and taking as little as four hours, is such a shock to a person’s fragile physicality (especially when the Aether and extreme temperatures are taken into consideration), that the demons sedate their mortal travelers, much as aliens might their abductee, even propelling them notably forward with magnificent force, all in order to sustain human life and overcome the otherwise impossible hurdles of lunar travel. Here we are exposed to the wealth of their devilish sorcery.

Perhaps the most menacing presence among Somnium’s many celestial inhabitants is in the specifics of the narrative itself, some of them being awkwardly true details concerning Kepler’s scientific theories, all of which also seem to invoke a biographical recollection of his own life. For example, Kepler and the boy share the same mentor, Tycho Brahe. He and the boy also stem from the same mother. And when the dream is cut short, we should not be surprised to read of a spiritual confession. Kepler wakes with his head covered, and he is wrapped in blankets just like the character in his story.

How much of “deep space” satellite imagery, I wonder, derives from the creative minds of angels and demons?

DISTANT SUNS… RATIONAL BEINGS… EVERLASTING PERDITION

BELIEF IN A PLURALITY OF WORLDS was as instinctive a conclusion to make as the “natural revelation” which fermented mankind’s very foundation of erroneous thinking apart from the MOST-HIGH’s Testimony. Looking back upon the Babylonian Mysteries earliest centuries, the stars themselves were worshiped as divine beings. When the luminaries became distant suns rather than the luminaries of old, they were conclusively inhabited by them. That distant unseen earths, each spinning around an unending swath of stars, were populated spread rapidly during the dawning hours of the Copernican Revolution—though some might argue the Italian astronomer is not to blame. While Copernicus declared the earth to revolve around the sun, he otherwise did not alter the accepted framework of Aristotelian cosmology.

For Copernicus, the fixed crystalline stars were still bounded by the outermost sphere of the created order. Copernicus was mainly concerned with the arrangement of the earth and wandering stars in relationship to the sun, and in doing so—rejecting the Bible’s belief in an immovable earth—he opened up the floodgates of perverted imagination. One contorted tinkerer of the mind hatches yet another magician, and then another and another. Astronomy needed new management, and Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) was eager to volunteer for the part.

|

Giordano Bruno—Rome, Italy |

Giordano Bruno’s book, On the Infinite Universe and Worlds, was first published in 1584 while living in London as the secretary of the French ambassador to England, and stands as a champion-feat of intellectual freedom. Queen Elizabeth granted intellectual opinion among foreign refugees, and though the first telescope would not be turned on a heavenly body for another twenty-five years, nor would the first wandering star, which was otherwise invisible to the naked eye, be discovered for another two-hundred, and though Bruno had certainly never taken up the discipline of astronomy, not even as a hobby, he was free to open up the heavens and fantasize. Perhaps that is why popular histories of astronomy often do not think to mention him. Bruno was not a scientist. He was a mind-tinkerer.

“In the first place, Bruno was not an astronomer,” writes Sylvia Engdahl in her book, The Planet-Girded Suns: The Long History of Belief in Exoplanets. “He was a philosopher. To be sure, all scientists were called philosophers in his day, since what is now ‘science’ was then known as ‘natural philosophy.’” But Bruno was a philosopher even by the modern definition. He did not watch the stars systematically; he simply thought about them. His theories were based not on observation, but on what he had read and what he was able to imagine.”

Bruno’s blind-belief in a myriad of planets is no longer opposed by the church. His vision of a universe infinite is now adopted by scientists everywhere. And finding a Biblical literalist who contests his insistence that a large number of suns inhabits those infinite spaces is far and few between. “That was the revolutionary concept Bruno originated,” writes Engdahl. “Others before him had suggested that there might be an infinite number of stars. But Bruno taught that stars are suns—or, more significantly in the implications both for his own fate and for the history of human thought, that the sun is only a star.”

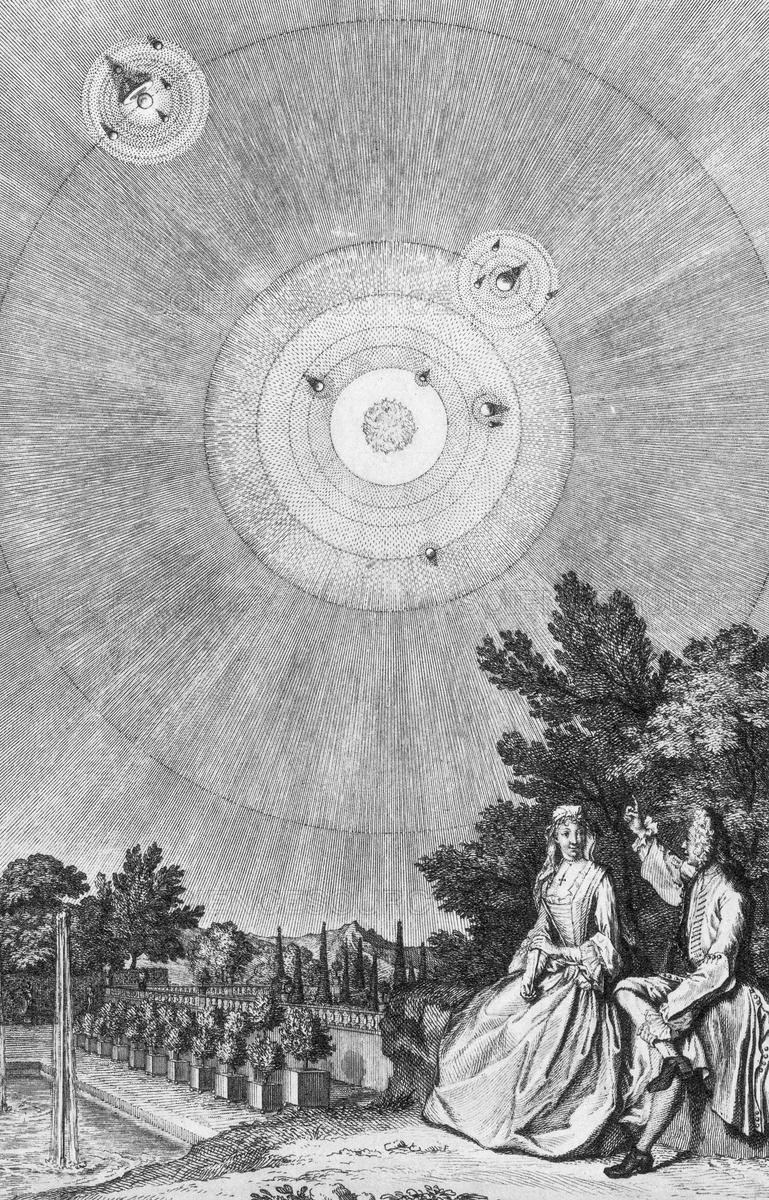

In as little as a century later, Bernard Fontenelle would carry Bruno’s apocryphal aptitude even further. His book, Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds, first published in 1686, successfully snatched Bruno’s plurality of worlds out of the philosopher’s hand and delivered it to the public. Finally, the average parishioner could open up the heavens, without Scipture to guide or advise them otherwise, and dream of alternate possibilities on their own. More specifically, Fontenelle garnished the adoration of women across Europe and America. In her essay, ‘Becoming a Scientist: Gender and Knowledge in 18th c. Italy,’ Paula Findlen writes: “No longer a man of the university, a scholastic master surrounded by male disciples, Fontenelle’s philosopher was a charming seducer of women, a wit who made science comprehensible by cultural analogy. His knowledge was no social liability that removed him from ordinary conversation, but the very reason that he held the attention of an aristocratic Marquise for several days and nights, as he educated her in the mysteries of the post-Copernican, Cartesian universe.”

During one starlit stroll, as Fontenelle’s narrative unfolds, the countess confesses to her courtier:

“You have made the Universe so large that I know not where I am, or what will become of me.”

Here the philosopher replies:

“I think it is very pleasant, when the Heavens were a little blue Arch, stuck with Stars, me-thought the Universe was too strait and close, I was almost stifled for want of Air; but now… I begin to breathe with more freedom.”

The philosopher commissions the countess with these words: “I find the fix’d Stars to be like our Sun, therefore I attribute to them what is proper to that: You are now gone too far to be able to retreat, therefore you must go forward with a good grace.” Fontenelle’s readers did just that—and never looked back. Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds made such an impression on cultural flights of fantasy that, according to one source, “Not long after, at the time of the death of Newton, vast amounts of sentimental poetry about other solar systems appeared in literary magazines, much of it by women and some based on the theme of Newton’s soul viewing other solar systems on the way to heaven.”

The poet Robert Gambol, in Beauties of the Universe, first published in 1732, presented a somewhat playful banter with his carefully disguised esoteric view of spiritual ascension into the cosmos when he quipped:

“Unbounded in its ken, from prison free

Will clearly view what here we darkly see:

Those planetary worlds, and thousands more.”

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, Cotton Mather of Salem witch trial fame devoted many pages in his book, The Christian Philosopher, to a plurality of worlds, and with as much willful vigor as any Christian who promotes and ultimately confuses Darwinism with a truly Biblical worldview today:

“Great GOD, what a Variety of Worlds hast thou created! How astonishing are the Dimensions of them! How stupendous are the Displays of thy Greatness, and of thy Glory, in the Creatures with which thou hast replenished those Worlds! . . . Who can tell what Uses those marvelous Globes may be designed for?”

In actuality, the sinful state of those creatures “with which thou has replenished those Worlds” was of much debate. Indeed, it was a perplexing puzzle. In Paradise Lost, which was first published in 1667, almost two decades before Fontenelle’s classic, the poet John Milton wrote: “Solicit not thy thoughts with matters hid…Dream not of other Worlds, what creatures there Live, in what state, condition, or degree.”

Regardless, men dreamt of other worlds. And philosophical questions, as well as the theological, plagued them. Scottish Astronomer James Ferguson wrote a book for children, Easy Introduction to Astronomy for Young Gentlemen and Ladies, first published in 1768 in London, whereas a conversation is held between a brother and sister. “I cannot imagine the inhabitants of our earth to be better than those of other planets,” his sister protested. “On the contrary, I would fain hope they have not acted so absurdly, with respect to him, as we have done.”

Unlike Mather’s wishful thinking, typical of the religious sort who embeds a charitable and wholly contradictory spin of apocryphal-tinkering into the MOST-HIGH’s Word, Benjamin Franklin exhumed the tragic, despairing words of a true humanist when he wrote:

“I believe that Man is not the most perfect Being but One, rather, that as there are many Degrees of Beings his Inferiors, so there are many Degrees of Beings superior to him. Also, when I stetch my Imagination thro’ and beyond our System of Planets, beyond the visible fix’d Stars themselves, into that Space that is every Way infinite, and conceive it fill’d with Suns like ours, each with a Chorus of Worlds forever moving round him, then this little Ball on which we move seems, even in my narrow Imagination, to be almost Nothing.”

Later in Poor Richard’s Almanac, dated September 1749, Franklin wrote: “It is the opinion of all the modern philosophers and mathematicians that the planets are habitable worlds.” In a letter to a friend, he confessed the natural conclusions to such beliefs: “Superior beings smile at our theories, and at our presumption in making them.” To another friend he expressed the wish that his idea of happy conduct might “grow and increase till it becomes the governing philosophy of the human species, as it must be that of superior beings in better worlds.”

On the 24th of April, 1756, John Adams confessed to his diary: “Astronomers tell us, with good Reason, that… all the unnumbered Worlds that revolve around the fixt Stars are inhabited, as well as this Globe of Earth.” Here Sylvia Engdahl writes: “That day and the next, he went on to reflect upon whether all the ‘different Ranks of Rational Beings’ in those worlds had committed moral wickedness, and if so, whether any church leaders would think they must be ‘consigned to everlasting Perdition.’ It is evident that he himself did not think so.”

Indeed, a Copernican or Darwinian worldview are two sides of the same coin. One can further see the very attitude which would grip and later define the Darwinian Revolution in as little as a century when English astronomer and mathematician Thomas Wright (1711-1786), having calculated that there must be “within the whole celestial Area 60,000,000 planetary Worlds like ours,” likewise said:

“In this great Celestial Creation, the Catastrophy of a World such as ours, or even the total Dissolution of a System of Worlds, may possibly be no more to the great Author of Nature, than the most common Accident in Life with us, and in all Probability such final and general Doom-Days may be as frequent there as even Birthdays, or Mortality with us upon the Earth. This Idea has something so cheerful in it, that I own I can never look upon the Stars without wondering why the whole World does not become Astronomers.”

An 1825 textbook for use in girls’ schools stated that to reject the idea of plurality of worlds would be “to narrow our conceptions of God’s character.” So popular was the alien mythology among the learned that in 1854 William Whewell, a prominent scholar of the history and philosophy of science and Master of Trinity College at Cambridge, published a book anonymously for fear that merely suggesting the Earth might be unique in housing intelligent beings, which was completely unorthodox in academia, might damage his reputation. Indeed, critics took notice. Whewell’s identity was soon divulged, despite not appearing on the cover or anywhere in print. And they were not pleased.

The London Daily News wrote in sharp criticism of Whewell:

“We scarcely expected that in the middle of the nineteenth century a serious attempt would have been made to restore the exploded idea of man’s supremacy over all other creatures in the universe… Nevertheless, a champion has actually appeared who boldly dares to combat against all the rational inhabitants of other spheres.”

Isaac Watts, best known for writing 750 hymns, including When I Survey the Wondrous Cross, and Joy to the World, perhaps best sums up the squandering tolerance and bleeding compromise of an apostate worldview, which is insinuated among the so-called Christian Darwinists of our day, by improperly force-feeding a narrative where it doesn’t belong. In ‘The Knowledge of the HEAVENS and the EARTH Made Easy,’ first published in 1726, Watts writes:

“It may be manifested here also that several of the Planets have their Revolutions round their own Axis in certain Periods of Time, as the Earth has in 24 hours; and that they are vast bulky dark Bodies, some of them much bigger than our Earth, and consequently fitted for the dwelling of some Creatures; so that ‘tis probable they are all Habitable Worlds furnished with rich Variety of Inhabitants to the Praise of their great Creator. Nor is there wanting some Proof of this from the Scripture itself. For when the Prophet Isaiah tells us, that God who formed the Earth created it not in vain because he formed it to be inhabited, Isa. XLV.18. He thereby insinuates that had such a Globe as the Earth never been inhabited, it had been created in vain. Now the same Way of Reasoning may be applied to the other Planetary Worlds, some of which are so much bigger than the Earth is, and their Situations and Motions seem to render them as convenient Dwellings for Creatures of some Animal and Intellectual Kind.”

In twisting the Prophet Isaiah for his purposes, as the Copernican must do, Isaac Watts, along with Cotton Mather and the lot of them, have disregarded Biblical fact for fancy. The MOST-HIGH never thinks to mention the imaginative planets of Giordano Bruno or the inhabitants resulting from them in His Word—mainly, because it took Bruno to perversely imagine them on his own. Elohim had no part in that. Indeed, He did not create in vain. The entire lot of stars, and let us not forget the Copernican’s pile-up of purported planets—1024 in number, or when written out, 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000—all of which are reportedly nestled within 200 billion galaxies, could only have been spoken into being on the fourth day of the creation week. It would only make logical sense that our master builder should first lay down the foundations and the ground floor of our house—mainly all of creation—before constructing its ceiling, as Moses attests to. The Earth was created in six days, and anything else brought into being on any other day of the week was done so in order that the unexpected cosmology might be fully appreciated by its only inhabitants.

“For thus saith YAHUAH that created the heavens; Elohim himself that formed the earth and made it; He hath established it, He created it not in vain, He formed it to be inhabited: I am YAHUAH; and there is none else (Isaiah 45:18).”

-Noel