Teenagers—an American Invention

IF THERE WAS ANY QUESTION AS TO WHY the silent screen actor Rudolph Valentino had earned himself the nickname “Latin Lover,” the unbridled screams of 10,000 women, who invaded his funeral in 1926—having died at the pre-mature age of 31—should erase any doubt. After Frank Sinatra’s legendary opening at the New York Paramount Theater in 1947 some two decades later, the clean-up crew found that the seats were still wet from the bobby soxers in attendance. Sweaty, throbbing, mind-pulsating young girls, contaminated with an almost alien case of hormones, were simply unable to compose themselves among the shock-and-awe swooning from the man who was later referred to as Chairman of the Board. In America, something was happening. One might think Bacchus, yet another counterpart of Apollo, and the wild Bacchant women arising within the Dionysian Mysteries—housewives mainly—who would be whipped up into a drunken frenzy whenever their favorite god came around for a forest romp, had returned.

Across the Atlantic pond the Brits were seemingly immune to the burgeoning howls of western sexuality. For a time they could only watch film reels manufactured by the very Americans who had recently helped to rescue them from nightly bombardment of Nazi Germany and which depicted youthful boys in lettermen jackets paired with girls in poodle-skirts, bobbing their pony-tails while guzzling Coca-Cola, milk shakes and hamburgers to the spells of a jukebox—attempting to make sense of it all. Liverpool’s John Lennon understood the difference between the youth of Britain and America. Some years later, after invading America with his mop-top quartet, the Beatle remarked: “America had teenagers. Everywhere else just had people.”

In John Lennon: the Life, author Philip Norman reports of the British, they “had regarded the process of growing up as perfectly straightforward. The system was that children went on being children until puberty was well advanced. Then, virtually overnight, they turned into grown-ups, wearing the same kind of clothes as their parents, aspiring to the same values, and seeking the same amusements. The effect of rioting hormones on immature and impressionable minds had yet to be studied in any depth by scientists or sociologists.”

When Elvis first shook his hips on a censured television screen in the spring of 1956, not even Lennon could resist. “He gave release to the tension that had built up in young men with no more global conflict to burn off than testosterone,” writes Norman. The very opening words of Presley’s first hit, Heartbreak Hotel, said it all. Well, since my baby left me… Elvis goes on to speak of a bellhop whose “tears keep flowing” and a “desk clerk dressed in black.” We learn of “broken hearted lovers” who end up “down at the end of Lonely Street.” Unlike the adult themes emanating from rhythm and blues, a musical genre which Heartbreak Hotel heavily borrowed from, Presley had—for the first time—channeled into and defined the teenage experience. According to Norman, it “reached directly to the primary adolescent emotion” and “melodramatic self-pity.”

We should stop and consider the absurdity of every parent’s worst nightmare—the sexual alienation of their one-time innocent child—and question why it is that we consider the teenager as gifted to the human experience by our Creator when psychologists have only recently materialized and grafted him into existence. But perhaps far more importantly, so have the capitalists. America, it seems, invented the teenager.

THEN AGAIN, FOR THE BULK OF HUMAN HISTORY, children as we know them today did not exist. Allow me to clarify. Antiquity will show they were dressed with the adult clothes of their social class in the months following one’s departure from the cradle. While the British may have succumbed to the revived Dionysian Mysteries in America’s music scene—partly due to the Beatles—in turn we may extend our stateside gaze across the Atlantic pond to witness the intellectual manufacturing of another modern upbringing. With the invention of the middle class, so too was the child developed as a sort of social etiquette to accommodate the Victorian era. And yet up until this time, one might imagine the grubby-cheeked, moist-eyed child of a Charles Dickens novel, without any protection from the hardships of the furnaces and the coal pits and the smoke stacks of the industrial revolution. “They were treated as short adults with responsibilities and with productivity demanded to the limits of their physical capabilities,” writes Carolyn L. Burke and Joby G. Copenhaver in Animals as People in Children’s Literature. Here Burke and Copenhaver further add:

“As a middle or merchant class developed, every person was no longer needed to work at providing the family income. With leisure came the opportunity to recreate the place of children in society. The emerging view declared that children needed extended time to develop before they would be able to take on the full responsibilities of adulthood. They needed guidance and instruction to maintain their safety and to allow them to grow into full membership in society. Play came to be viewed as child’s work during which they were discovering and practicing lessons, and pleasure came to be seen as an enticement in this process.”

There is a rather strange spiritual phenomenon which came into being through the advent of the Victorian child. Animals with human characteristics began to appear in children’s literature. For this, we may thank Mr. Charles Darwin. Before the theory of evolution and On the Origin of Species, first published in 1859, we are hard pressed to find animals which take on a coat and trousers and a thankless job—essentially a soul. With Darwin’s ape unexpectedly showing up at the family reunion of man, the Bible’s eye-witness account that we are “created in the image of God” was so thoroughly shaken that the very promise was also extended to nature. Once again, the parent embraced pantheism for his child—long thought dormant—and if literature soon had its way, the wood just beyond the garden wall was dripping with fairies and pagan spirits in the dew.

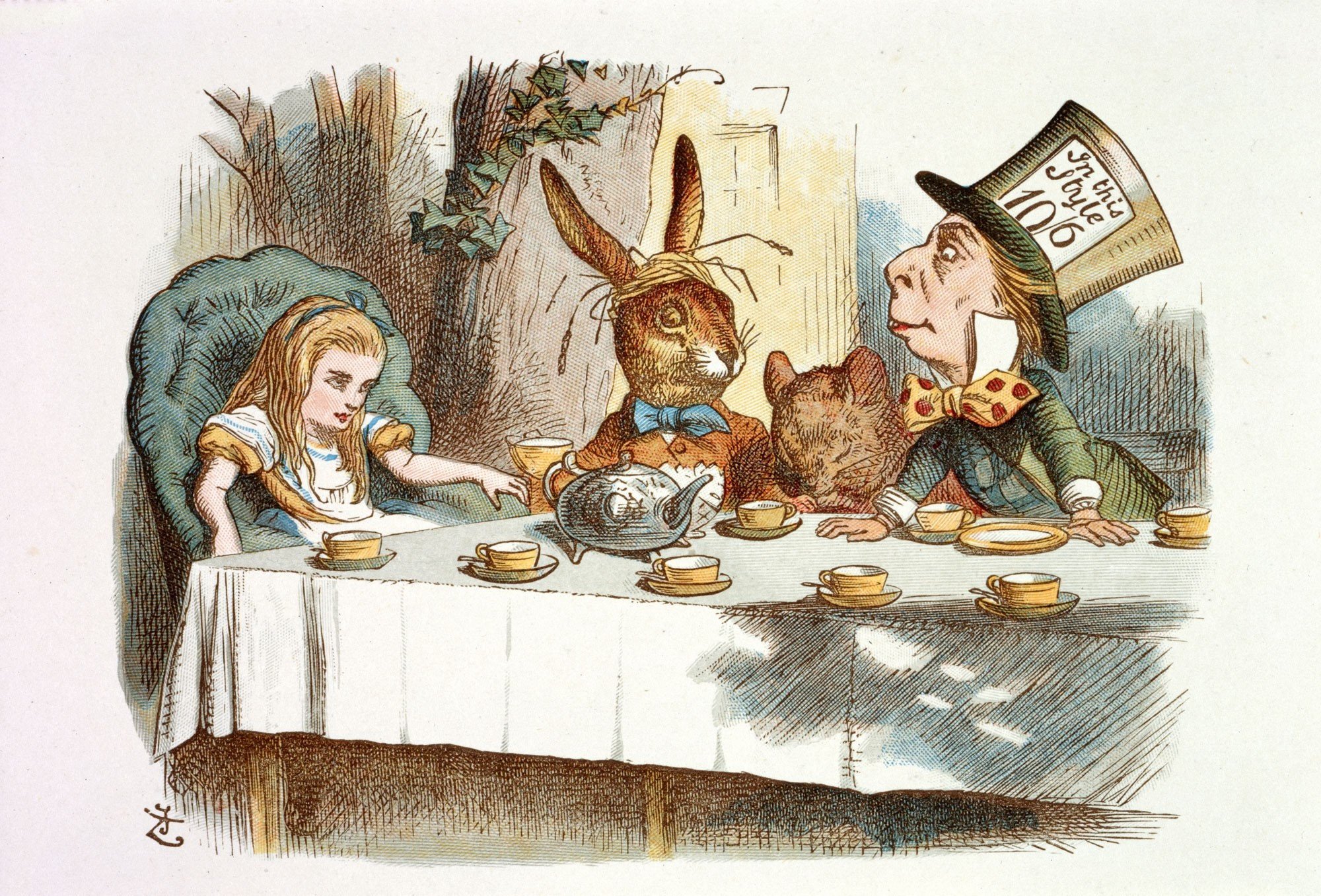

In the immediate aftermath—within six years of Darwin’s publication—three significant texts were delivered unto the newly developed Victorian child. Margaret Gatty’s Parables from Nature and Charles Kingsley’s The Water-Babies attempted to educate the reader with their own responses to the Darwinian controversy, with Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland delving even further into the magnum opus of literary nonsense. As a biologist, Gatty sought to challenge the arrogance and materialism she saw in the Darwinian Theory. Her rebuttal however was an odd choice. After campaigning Sir Thomas Browne’s quip that “there are two book from whence” he collected his “divinity;” the first being the “written one of God, another his servant, Nature—that universal and public manuscript that lies expanded unto the eyes of all: those that never saw Him in the one have discovered Him in the other,” Gatty writes from a narrative in which animals and plants are valorized above their arrogant male doubters, thereby subverting the overt didactic message of her evangelical text. If she were attempting to re-direct the child’s attention to the Bible’s promise that we are created in God’s image, and therefore not evolved, then she failed miserably.

Quite contrarily to Gatty’s oppositions, Kingsley had been one of the first to praise Darwin. He even received an advanced copy. On the 18th of November, 1859, four days before On the Origin of Species hit store shelves, Kingsley wrote that he had “long since, from watching the crossing of domesticated animals and plants, learnt to disbelieve the dogma of the permanence of species,” and had “gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of Deity, to believe that He created primal forms capable of self-development into all forms needful pro tempore and pro loco, as to believe that He required a fresh act of intervention to supply the lacunas which He Himself had made,” asking “whether the former be not the loftier thought.” Kingsley took his love of evolution to the child, and by doing so once more redefined him—once believed to have been created in God’s image—as recapitulative. Kingsley preferred fantasy as provisions for a new myth, one which dangerously integrated the Christian faith with Darwinian evolution—and so much more. For example, in The Water-Babies, Kingsley argues that no person is qualified to say that something never seen—whether a human soul or a water baby—does not exist. To this effect he writes:

“How do you know that? Have you been there to see? And if you had been there to see, and had seen none, that would not prove that there were none … And no one has a right to say that no water babies exist till they have seen no water babies existing, which is quite a different thing, mind, from not seeing water babies.”

Nearly a century later, Christian academic and medievalist C.S. Lewis would successfully wed the pantheism of pagan religion with the faith he was accredited of being a spokesperson for through the publication of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe in 1950. The church bought it—for the most part. One might wonder if the spirit of anthropomorphism, which apparently possessed his childhood imaginations, were first developed under the pupilage of Beatrix Potter.

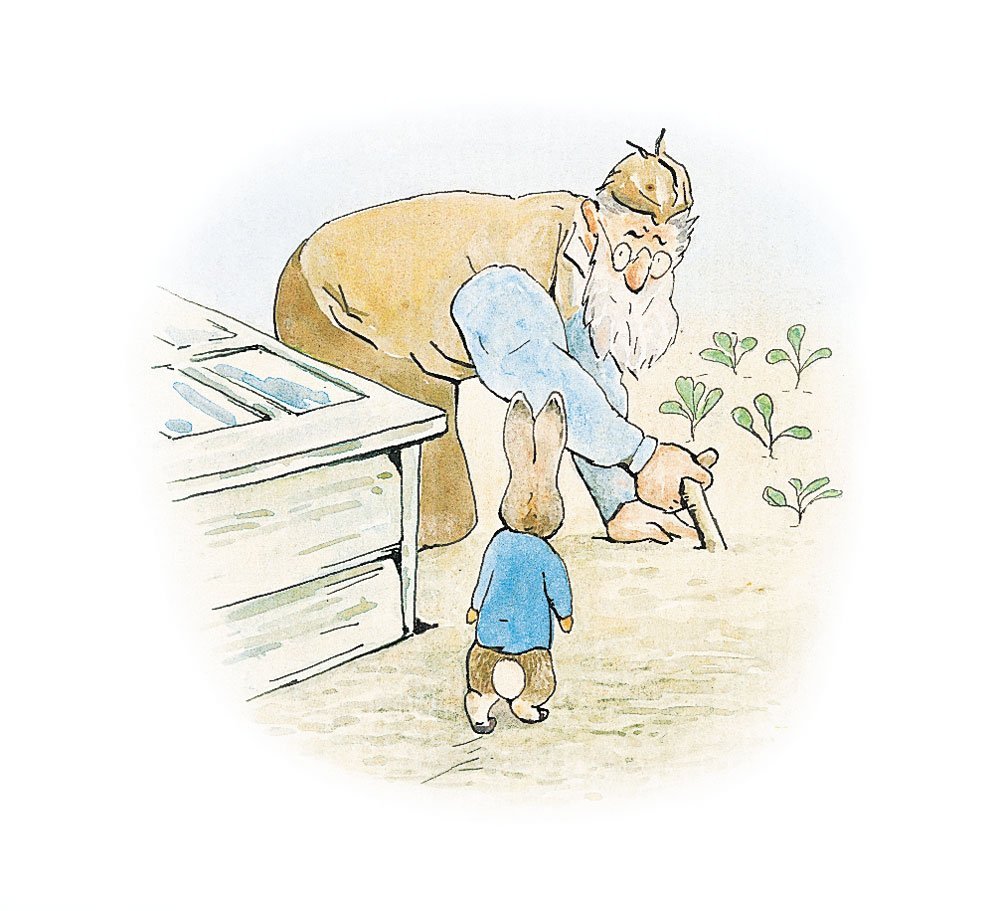

With The Tale of Peter Rabbit, published in 1902, the rabbits are first shown as normal, realistic animals in the woods. The next scene depicts Peter and his three sisters as being dressed by their mother and handed baskets for collecting produce. And yet, after meddling in human affairs—specifically, Mr. McGregor’s garden—Peter’s jacket causes him to be trapped in a net, and his shoes slow down his running. From beginning to end, Potter’s first offering is a brilliant page-turner. Despite its natural English setting, “this beautiful, idealized place,” writes Margaret Blount, suddenly “made the fantasy more real and the pleasure more possible, the animals’ humanity…more natural.”

We are presented with a rather strange opportunity. Parents would happily deliver their children to animals for tutoring privileges in reading, math, and any number of developing social skills—basically what it is to be created in God’s image. I know I have. As I write these words, my children in the other room watching the Muppets of Sesame Street. It just goes to show that today we are no better off than our spiritual forefathers—morally speaking. We have succumbed to the seemingly living, breathing, animated and god-like idol of Babylon we call television in order that the spirit of anthropomorphism which possesses it may help in the process of raising them. We let animals teach our children. How forward thinking and evolutionary of us! In the bulk of Judeo-Christian history, I can’t help but wonder—would the church stand for this; would they see us as lukewarm; would they even call our Easy-Believism in the ways of the world moral? Most will disagree. I will surely find myself outnumbered. Psychologists are gifted at convincing us of its benefits.

IT IS NO SECRET that Jesus broke with human tradition. He laid hands on children and blessed them, and is recorded in three separate Gospels as having asked His disciples that they “suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto Me (Matthew 19:14).” Such a thought, that a rabbi would contend with children, was repulsive. And yet, because a young child is destitute of ambition, pride, contemptuousness, and hypocrisy, he or she is therefore teachable.

Jesus had a way of flipping the tables, not only in His Father’s house, but with the uncountable Luciferian institutions of the mind. In His Father’s kingdom—we shall come to learn—the only way to ascend up into heaven is to first go down. James the brother of Jesus phrased it like this: “Humble yourselves in the sight of the Lord, and he shall lift you up (James 4:10).”

Children must depend upon their parents for food and clothing, proper discipline, spiritual training, and even a roof over their heads. They are highly receptive and seemingly incapable of producing good works to merit heaven. Like these we are to become, open to His provisions and not depending upon our own presumed goodness. This is to contrast the rich young man who thereafter approached Jesus and asked of Him, “Good Master, what good thing shall I do, that I may have eternal life?” We are told he “went away sorrowful: for he had great possessions (Matthew 19:22).”

Today we have teenagers to contend with. Mrs. Hadley and I will have two of them in as little as several years. Fact is childhood has been extended dramatically from the few years it was originally intended until the individual person feels good and ready. There was a time not so long ago that the child grew up when the parent was good and ready. If they worked around the house, it’s because the home was a business. The Luciferian governments of our world have certainly taken advantage of this increase—they likely even had a hand behind it—and those of us inhabiting this joyous cosmology shouldn’t be surprised to find the public school system developing as a rib partner with the advent of modern childhood. It is just like our ruling authorities to convince us we need an ever-expanding universe of time within the mind of each young person for nurturing apart from the morals of his parent.

Thirty is the new twenty—I am told. Some will say technology is to blame, others the economy—or perhaps both. The thing is, our current gauntlet of Hollywood blockbusters are movies which were once intended for children and are geared now towards a certain standard of thinking—drained of the intellectual meat which might have filled the pages of scripts in past decades. The various Comic Cons across the United States, a tradition which began in San Diego, are attracting upwards of 200,000 attenders—mostly adults. And the Walt Disney World resort rakes in 50 million visitors per year. While not all attenders are traveling with children, even Disney adopts a certain standard of thinking.

When prompting us to suffer little children, and forbid them not, to come unto Him, Jesus did not promote the artlessness of a child’s own indiscretion, a feeble mind which is easily drawn to myths and fantasies. Jesus was not promoting that ever-widening gorge in a man’s life which the psychologist and the capitalist and the government may plug into and steal from. While I am in no way promoting other human institutions, particularly the excesses and cruelty of child labor; the predominant view before Victorian times—that we leave the crib and the milk of our mother and digest the meat of Godly maturity, backed with sound Biblical doctrine, and wielding our very being with the morality of our spiritual forefathers—is most certainly a Biblical attitude. Childhood is a state of mind, which Holy Writ only thinks to speak of in passing.

To this effect, the Apostle Paul writes in 1 Corinthians 13:11:

“When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

As if creating the teenager was not enough, nostalgia has become an entire industry in and of itself. Adult human souls are monetized and expected to relive childhood memories through an ever deepening well of the mind in which—if correctly executed—we are never expected to climb out of.

Noel

JOIN OUR NEWSLETTER!

Stay up to date on the latest articles and news from Noel.