Satanic Panic: The Day E.T. Visited the UN

THE BABYLON WORKING

BY DAY, Jack Parsons launched the Cold War. By night, the founder of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory emerged from a coffin to perform the Enochian magic first began by Englishman John Dee. His own esoteric works were often mixed with his scientific experiments, and it has been reported that Parsons attempted to invoke spirits while working with rocket fuel. His mentor Aleister Crowley had espoused science with the practice of sex magic, Kabbalism, rites taken from Freemasonry and medieval grimoires—a quest which Parsons could stand behind. Parsons used his own salary to conduct occult experiments in hopes of ushering in a new age of magical freedom. In the Mojave Desert, he and Church of Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard were attempting to invoke the power of a goddess. This divine being—identified by Crowley as both the Biblical whore of Babylon and the goddess Ishtar—would usher in the end to an age of repressive Christian morality.

It was 1946. They dubbed the project “the Babylon Working.” And on the 18th of January, only two weeks into their fusion of sex-magic, Parsons announced to Hubbard:

“It is done.”

The Day E.T. Visited the U.N.

THE LOS ALTOS Drive-In Theater, once located at 2800 N. Bellflower Boulevard in Long Beach, California, where I watched such classics as Raiders of the Lost Ark, Back to the Future and, in its final hours before closing, Jurassic Park, is now a typical shopping mall, complete with the ho-hum-drum of a Papa John’s Pizza and K-Mart. Upon its wide release on June 11, 1982, E.T. invaded every American city and suburb. Within two weeks, Reese’s Pieces sales tripled. Variety’s McCarthy critiqued E.T. as “the best Disney film Disney never made.” Mrs. Hadley would have been only a few blocks away and just as many weeks old when I participated in my own screening of the film from the front seat of the family wagon, and I can distinctly recall walking around the church parsonage in Hawthorne, California endlessly rehearsing: “E.T. phone home! E.T. phone home!” This is likely due to the fact that my parents documented those persistent words on cassette tape, and for years thereafter I wore out the ribbon by rewinding and playing my performance on the very Japanese-made Panasonic that had earlier recorded it.

But I wasn’t the only one. Neil Diamond wrote a hit song, Heartlight, based on the film’s central tropes. Michael Jackson not only purchased one of the working puppets used in the film but—in a somewhat more masterful performance than my own—can be heard crying at E.T.’s death during his own special LP-length recording. At President Reagan’s request, Spielberg held a private screening in the White House. The First Lady cried during the films third act. Then again, so did The Gipper. Spielberg told Twilight Zone Magazine; the leader of the free world could not withhold “a little moisture in his eyes. I view that as a very positive sign.”

On the 17th of September, E.T. made an unprecedented appearance at United Nations headquarters in New York City. Twilight Zone Magazine writer David Shifren was on hand to witness the event and interview its director. He wrote: E.T.’s “United Nations debut came before a standing room only crowd of foreign dignitaries, consulate members, and UN staffers who saw the young director received the UN’s Medal of Peace, the first time the prestigious award has ever gone to a filmmaker. They then watched a special showing of Spielberg’s blockbuster hit, E.T.” Shifren adds: “Despite the event’s formal setting—the UN’s spacious Trusteeship Council Chamber, where almost every seat bears an official placard naming a member country—the audience was completely swept up by the film.” They applauded enthusiastically during the closing credits, particularly for Spielberg’s name, and cheered during the more exciting scenes.

The “UN and E.T. are one and the same,” Spielberg said in his acceptance speech. “They both have the desire and the need to communicate, to care, and to love. This film is dedicated to all children of all ages.” Further voicing approval for the UN, Spielberg concluded: “The United Nations represents everything that E.T. stands for—love and communication.”

E.T.’s arrival at the UN did nothing to massage the nerves of right-wing evangelicals. Eschatological-minded Christians had long been suspicious of the UN’s potential to fulfill the prophecies of Daniel and the Apostle John. By making this the case in The Late Great Planet Earth, Christian Zionist and dispensationalist author Hal Lindsey prompted an entire baby-boomer generation to gaze up at the clouds for Christ’s return. While science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke had already called out the aliens bluff, detailing them as your run of the mill Biblical devil and then being so bold and perverse to glory at their destined arrival in Childhood’s End (1953), the books of Christian author Frank Peretti would be instrumental in cementing the alien-demon connection. The blood of American radio host and televangelist Bob Larson simply boiled over the connections he made between rock music and Satanism. His book, Satanism: the Seduction of America’s Youth persuaded countless parents that forces were influencing America’s youth through “ghoulish games, horror films, black metal music, and drugs, as well as the occult enticements” in hopes of selling their souls to Satan. Dungeons & Dragons was criminalized in the church. And as most online reviews by a grown and apparently bitter millennial will show, Phil Phillips book, Turmoil in the Toy Box (1986), pillaged and plundered the playtime carpets of countless childhoods by convincing their parents that He-Man, G.I. Joe, Star Wars, My Little Pony, and Smurfs were laced with occult ties.

I remember it well.

In an interview with io9, Peter Bebergal, author of Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll, said, “It was something we didn’t realize at the time, but now, it looks like a low-scale version of the McCarthy-era paranoia around communism. The devil worshipers could be anywhere. They could be your next-door neighbor. They could be your child’s caregiver.” He furthermore added: “A lot of it was having a spiritual vacuum, created by the fact that the 1960s promise of this cosmic, spiritual consciousness didn’t really pan out. Then you had this 1970s uptick of paranormal investigations, ESP, an interest in UFOs, really climaxing with Close Encounters of the Third Kind. But the aliens never actually landed, you know? I think it led to a cynicism that led to kind of a cultural paranoia: there is no meaning. There was already an uptick in fundamentalist Christianity. The Reagan Right had begun to dominate politics. And it was the beginning of a cultural war; that’s when the Parents Music Resource Center started to put labels on album covers to warn against profanity or even references to the occult. It was a perfectly ripe stew for Satanic Panic. In a way, believing that Satan is running the world is still offering a kind of order to things, in a world that can feel very disorderly.”

And yet the Satanic Panic which once sent the baby-boomer generation into a tailspin is no more. More precisely, it is but a whimper—already doomed to messy back-filing in the annals of discomforted minds. Somewhere along the way the Christian dusted his devil-worshiping Led Zeppelin album off and returned it straightway to their turntable, callously shrugging as he did so. Despite Jimmy Page’s lifelong devotion to Aleister Crowley, I can only deduce that songs like Highway to Heaven—particularly Page’s clear pronunciation of “Hail Satan!” when played backwards—means little but theatrics to the haphazard person who deceives himself into claiming a love for the Savior while singing along. The devils music has become family entertainment. For many—and dare I say most—the Spirit is thoroughly quenched. Looking back on it all, there is a tragically missed opportunity in Christian musician Keith Green’s 1977 song, Nobody Believes in Me Anymore, which was written from Satan’s perspective and played as an anthem for the Satanic Panic generation.

Most seem to paint the Satanist with shades of Shakespeare; the “double, double, toil and trouble, fire burn and cauldron bubble,” of the Three Witches of Macbeth, or Wayward Sisters—one of the most famous lines in English literature, rather than the real thing. Rumors of poisoned Halloween candy and Druid-like childcare workers abounded, in part thanks to daytime television. Mention of the Kabbalists, the alchemists, or the mystics of Science were altogether muted. In the end, the Satanic Panic crowd based much of its content on broad-sweeping theatrical generalizations, chasing after wind-swept caricatures and the elongated shadows of gnats rather than real magic; the kind which saturates our very cognition through the alpha waves of television and with the potency to program; the kind of magic which sends men to the moon and, in the most delusional of indoctrination power, changes the shape of the earth.

After publishing Trouble in the Toy Box and its follow-up, Saturday Morning Mind Control; authoring 15 books in total and selling 1.3 million copies; and succumbing to a stool and dunce cap of ridicule, author Phil Phillips is currently the president of God Loves Kids, a mission’s organization caring for almost 4000 children, and which currently builds orphanages in Nepal. Phillips came to warn us. Most laughed. The thing is, much like the Satanic Panic movement which prompted him to action, many of his ideas seem ill-considered. For example, when warning parents of the Occult’s almost-omnipresence in E.T., he seems to get some details wrong in the investigation, such as the children “playing Dungeons & Dragons in the opening scene,” which makes one wonder if he actually saw the movie to begin with. And according to Phillips, E.T. “tells Elliott that he’ll always be with him in his heart.” For someone playing the part of town squire, he tragically mismanages an important detail—assuming he took the time to see the movie at all.

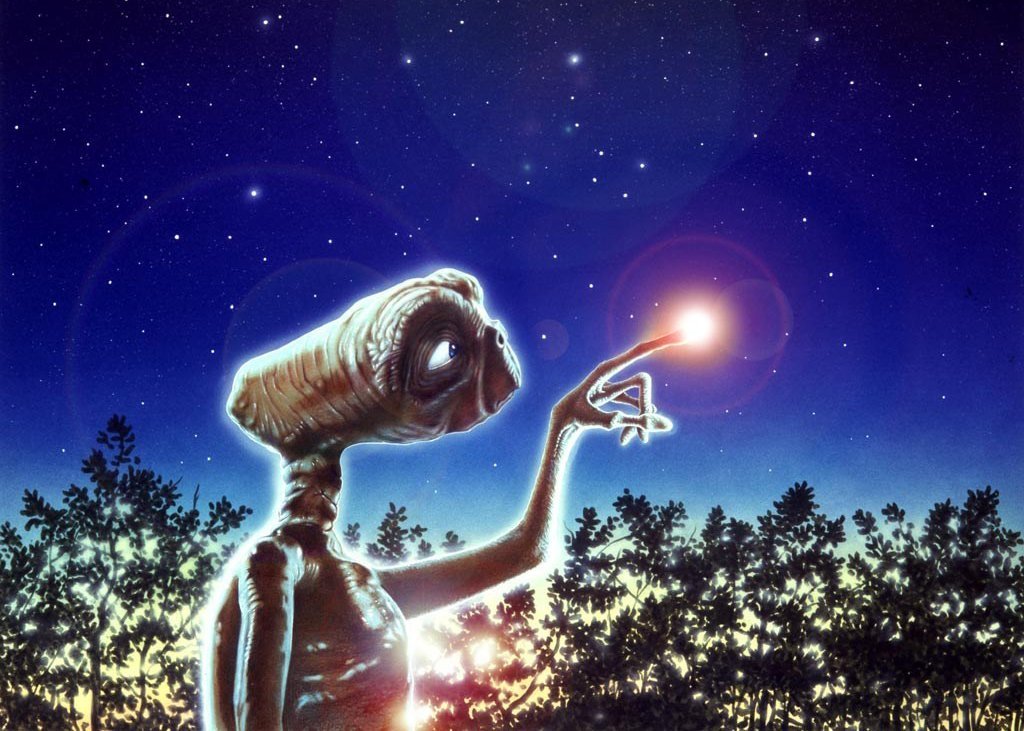

E.T. doesn’t tell Elliott he’ll “be with him in his heart.” What E.T. actually accomplishes to get away with is far more frightening, and precisely why the Satanic Panic crowd seemed to be grasping at straws rather than spiritual discretion. The movement perished for lack of knowledge. With a glowing fingertip E.T. points to the boy’s forehead and assures him, “I’ll be right here.” By turning our attention to Elliott’s third-eye, E.T. has just given himself away. He is not truly a cosmic traveler. He is as old as the angels, which according to Enoch, conspired to take human wives on Mount Hermon—I shall explain why in a moment—and likely accommodated them. And his method of waking up is older. With his long, glowing finger reaching out like the hand of God in Michelangelo’s famous painting—an image used for the film’s promotion and which seemingly went unchallenged—E.T. is Elliott’s astral-guide.

Even Neil Diamond seemed to get the memo. With Heartlight he wrote:

“Turn on your heartlight

In the middle of a young boy’s dream

Don’t wake me up too soon

Gonna take a ride across the moon

You and me.”

Further generalizations and unsubstantiated rumors only make Phillips claims ill-considered when he reports a recent “conversation with one screenwriter of E.T., a man deeply troubled at his involvement with the movie. He told me about the visual subliminals the screenwriters wove into the movie, many of which were specifically designed to enhance the reputation of and change the nation’s thinking about the homosexual community.” This is as far as Phillips dares to go—perhaps because he did not actually have the capacity to recognize subliminal homosexuality while keeping on the lookout for them. He could have mentioned the shed where Elliott first meets E.T., or the Reese’s which he cleverly coaxed him to his bedroom with, or the woman’s clothing which Gertie dresses him in—or the fact that E.T. was never conclusively identified as male or female. In fact Spielberg confessed to writing E.T. as an asexual creature, which only complicates the films budding pubescent sexuality. Consider E.T. getting drunk with an indiscriminate portion of beer. Telepathically. Elliott also succumbs to drunkenness at school. When E.T. watches John Wayne kiss Maureen O’Hara in a televised broadcast of John Ford’s ‘The Quiet Man,’ we are left to ponder whether E.T. was sexually stimulated by Wayne or O’Hara. And when it comes to subliminal messaging, let’s not overlook the rainbow which clearly breaks God’s own laws of natural science to paint a starry sky at E.T.’s departing.

One thing is certain. Those who refuse to acknowledge the work of Satan in the world were immediately capable of critiquing the film’s underbelly to America, and with remarkable acuteness. As the 1980’s dawned, conservative familialism was maintained under the protection of patriarchal culture and sought to vilify unconventional families—such as gays and lesbians as well as single parents. It actually mirrored the Satanic Panic with its widespread fear that a battle of good versus evil was raging just below the surface of American culture. In the face of soaring divorce rates—which more than doubled between 1970 and 1980—and widespread invocations to sustain marriages at all costs, E.T. simply spun that around and gave us a look at the alternative. Actually, that alternative brought America to tears. Whatever the outcome of Elliott’s blossoming sexuality may prove to be, one thing remained certain. His father had run off to Mexico with another woman and his mother was on the verge of emotional collapse. And yet the child of divorce could not only survive, but also thrive. In short, the family would get along just fine. After its premiers at the Cannes Film Festival, film critic Pauline Kael wrote in The New Yorker: “It is bathed in warmth and seems to clear all the bad thoughts out of your head.” Film critic Marina Heung maintained that “the enduring appeal of E.T. inheres in the dissolution of the nuclear heterosexual family over the latter half of the twentieth century and the concomitant threat posed by this disintegration to many believers in the nuclear heterosexual family’s powerful, and presumably positive, effect on child development (Making E.T. Perfectly Queer, Brooke M. Beloso).” It is an “odd little love story between an alien and a child,” wrote Thomson of The Guardian, which clears those “bad thoughts.”

In the E.T. Storybook, based in part on Melissa Mathison’s screenplay and released with the movie’s premiere, author William Kotzwinkle describes the alienated alien with all the zig and zag lines of a modern Renaissance Man—the artist, inventor, healer. His race is described with “misshapen heads, their drooping arms and roly-poly, sawed off torsos” One might mistake him for a goblin, with his “enormous bulbous eyes” and “webbed feet coming almost directly out of his low-hanging belly and his long hands trailing along ape-fashion behind it.” What particularly strikes my interest is the mystical woods, still untouched by the bulldozer and which rises high above Elliott suburban home, where we first meet him. Bunched together amongst the flora, one might mistake them for “little old elves caring for their misty, moonlit gardens,” which would “make one think of elfland, and the tenderness they showed the plants might add to this impression.” E.T. and his crew of botanists were very old, for they had “collected everything that grew or had grown on Earth throughout its existence,” including what only remains now “in fossil form, imprinted in coal.” The botanist has had “millions of years’ experience” on Earth, Kotzwinkle assures us. E.T. is the perfect description of the Watchers who, for thousands of years, have invigorated the Mystery Religion and cultivated the wisdom as well as Sciences of Eastern and Western civilization. “He loved Earth, especially its plant life, but he liked humanity too, and always, when his heart-light glowed, he wanted to teach them, guide them, give them the stored intelligence of millions of years.”

Space itself is the grand illusion. Being first and foremost a botanist, we find E.T.’s meaning in the Pagan religion from which he originated from—animism and pantheism. The little garden gnome not only watched over the physical preservation of Earth’s vegetation, but their souls. Wandering off the fire road into Elliott’s backyard—a path which carried him down like a god from the mountain—Kotzwinkle further elaborates on his extraordinary gifting: “Something in the yard was sending soft signals. He turned and saw the vegetable garden. He crept toward it, embraced an artichoke, and asked the vegetables what he should do. Their advice, to go and look in the kitchen window, was not welcome. The artichoke insisted, grunting softly, and the extraterrestrial crept off obediently.” And then, when the pizza delivery person arrived, E.T. panicked. “There’s nothing to fear, said a tomato plant. It’s only the Pizza Wagon.” When E.T. dove into the shed to protect himself, he found tools, particularly a diffing fork with which to defend himself. “Don’t stab yourself in the foot, said a little potted ivy.” E.T. could feel the life of the orange diminish as it was plucked from a tree. Like a true fairy of Theosophy, E.T.’s spirit seemed interlocked with a common house plant. When E.T. died, so did the geranium.

There is another ingredient to E.T.’s role as a Watcher of old. He was conjured.

Elliott’s mother Mary—only recently divorced and in dire need of excitement in her life—we are told by Kotzwinkle, looks strangely upon her two sons and their friends as they play Dungeons & Dragons with “their six-sided cube” in her kitchen, a “rubble of a ruined city of Crush bottles, potato chip bags, books papers, calculators.” She tries to make sense of their talk.

One voice says, “So you get to the edge of the forest, but you make a truly stupid mistake, so I’m calling in the Wandering Monsters.”

And then another, “Can I get Wandering Monsters called out for just befriending a goblin?”

“Steve’s Dungeon Master,” that would be her son Michael, “He’s got Absolute Power.”

Absolute Power, Mary sighs. But she couldn’t even get them to dry a dish.

And then Elliott—she recognizes the voice of her second-born—shouts: “I run down the road. They’re after me. Just when they’re about to get me and they’re really mad, I throw down my portable hole. I climb in and pull the lid closed. Presto. Disappeared into thin air.”

‘Portable hole? If only I had one to disappear into,’ Mary thought.

What she doesn’t realize—what none of them do—is that an actual demon is being conjured through the ritual. In fact, Elliott has rather arrogantly laid out a precise plan of action for his astral-guide in the days to come. Within moments the two will meet under the light of a waxing moon like something from Aleister Crowley’s Moonchild. We should recognize some semiotics at play—it is rather Kabbalistic in nature—because the letters “E” and “T” begin and end with the protagonist, Elliott, therefore foreshadowing the mystical connection that the two will share. That said, the feminine moon, with her wealth of esoteric potency, is a major player in the unfolding drama—despite not being listed in the closing credits. E.T. and Elliott’s soaring flight on a bicycle made for two will bypass the light of the moon at its fullest. This will occur on Halloween night, which is also the ancient druidic festival of Samhain; a dreadfully important moment in the pagan and occult ritual calendar. Samhain is the night when the gates and doors to the “otherworld” are opened, and the spirits of the dead enter our realm. It is also the very night in which E.T. sets up his computer to call upon them.

This is precisely the significance of the shadow government scientist played by real-life Marxist Peter Coyote, but whom we only know as Keys. For most of the movie we never see Coyote’s face, only the keys jingling from his belt. On the esoteric level his flashlight reminds us of the hidden knowledge which pierces the darkness. However we need also reference the Key of Solomon, an Occultist text of the Italian Renaissance—typical of Renaissance Occult-Science—which is inaccurately ascribed to King Solomon but deals with conjurations, invocations and curses to summon and constrain spirits of the dead and demons in order to compel them to do the operator’s will. Aleister Crowley translated one version of it. With E.T., the Scientists of the shadow government are non-other than wizards attempting to summon a botanical gnome—not spacemen. Considering all this and what we know of Aleister Crowley, Jack Parsons, and Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which created the American space program, the fact that government occultists arrive up to apprehend E.T. dressed as NASA astronauts lends further credence to this movie representing one massive ceremony.

Imagery stylized after a Kubrick move seems to fill every frame. Remember when an intoxicated E.T. watches John Wayne kiss Maureen O’Hara on the television? While this transpires, we cut to Elliott’s classroom, where three distinct posters depict Voyager, Jupiter, and Io. Voyager was the mission that sent probes to Jupiter and Saturn in the late 1970’s—all thanks in to Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

In Magia Sexualis, author Hugh Urban described Crowley’s use of sex magic as a powerful means to shatter the limited rational mind and finite human ego. “However, the ultimate goal that Crowley sought through his sexual magic went far beyond the mundane desire for material wealth or mortal power. In his most exalted moments, Crowley believed that he could achieve a supreme spiritual power–the power to conceive a divine child, a godlike being, who would transcend the moral failings of the body born of mere woman. This goal of creating a divine fetus, Crowley suggests, lies at the heart of many esoteric traditions, from ancient Mesopotamia to India to the Arab world: ‘This is the great idea of magicians in all times–To obtain a Messiah by some adaptation of the sexual process. In Assyria they tried incest…. Greeks and Syrians mostly bestiality…. The Mohammedans tried homosexuality; medieval philosophers tried to produce homunculi by making chemical experiments with semen. But the root idea is that any form of procreation other than normal is likely to produce results of a magical character.’ Sex magic, particularly in its transgressive, non-reproductive forms, can thus unleash the supreme creative power: the power to create not an ordinary fetus, but a magical child of messianic potential.”

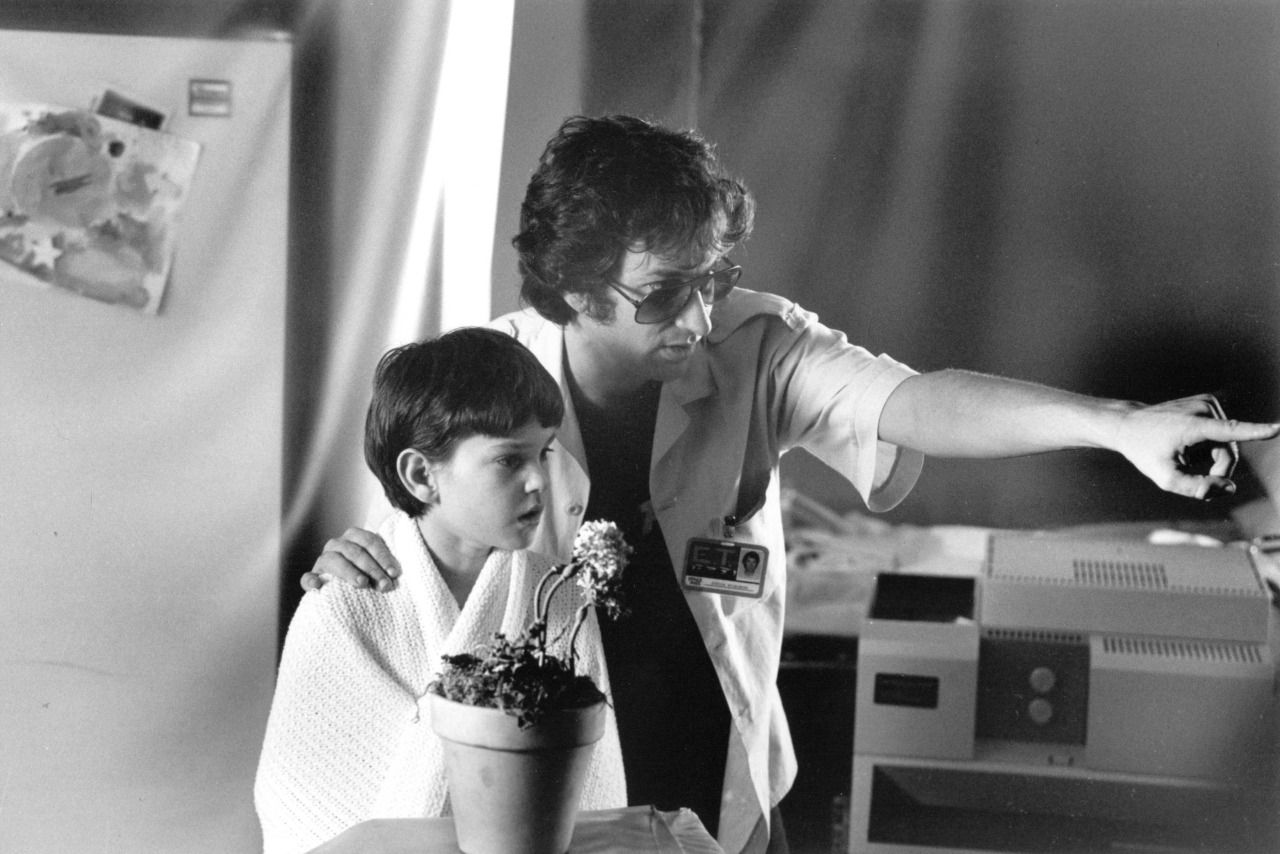

Even the movie itself was filmed in a pomp in ceremonious fashion. If one watches the DVD commentary, Drew Barrymore reminisces that E.T. was like a “guardian angel for them,” insisting that he was almost real. We can surmise that E.T. is a type of reptilian creature, which is best hinted at when he telepathically commands Elliott to free the frogs moments after scriptwriter Melissa Mathison’s husband Harrison Ford tells his class: “the frogs won’t feel a thing.” E.T. has Kundalini energy about him—a serpent presence—or what the Occultists would gladly call, “the light bearer.” E.T. fills each shoe nicely. Steven Spielberg once told The Best of Starlog: “There was a severe reverence on the set shown by everybody, even the guys who swept the floors, toward E.T. Severe reverence… The kids believed in E.T. the way we believe in Santa Claus… or should believe in Santa Claus. Everybody had such a belief in E.T. as a living, breathing, organism that no one would dare go up to him and make fun of his appearance or make fun of his awkwardness. He really did seem to have a life of his own.”

“Elliott, your friend is a rare and valuable creature,” Keys tells Elliott in Kotzwinkle’s Storybook, “We want to know him. If we can get to know him, we can learn so many things about the universe and about life.”

Keys fictional words line-up with Spielberg’s. He told Twilight Zone Magazine: “I think that, in the presence of an extraterrestrial, the United States government or any government of the world would want knowledge, not conflict or hostility. I believe that we will solve all our own problems—but I would be nice to know that there’s somebody up there who likes us. It helps.”

Dare I call E.T. Satanic? But I will—I must. There is hardly a worse cause for mockery than to call anything for what it is. To call rock culture Satanic in a serious way or to accuse Hollywood of the same damnable falsehood is cause for a burlesque rebuttal. That is because hardly anyone—and I include much of the Satanic Panic generation in this—seems to grasp the implications of Yeshua’s pacifism when He answered in John 18:36:

“My kingdom is not of this world: if my kingdom were of this world, then would my servants fight, that I should not be delivered to the Jews: but now is my kingdom not from hence.”

Azazel had already taken Yeshua to “an exceedingly high mountain, and showed Him all the kingdoms of the world and their glory,” as Matthew records. And he, being the devil, said to Him, “All these things I will give You if You will fall down and worship me (Mathew 4:8-9).”

Yeshua did not dispute the devil. He certainly didn’t call him a liar. It is indeed an eye-opening moment to shed the pounds of cognitive dissonance and come to the awareness that Satan fully manages and operate the kingdoms of the world—all of them. I hope I am not being cavalier. I certainly didn’t stumble upon this realization—or rather, the scales which had likely been placed over my eyes the very year I was born were not shed—until I discovered what the Bible said, and what’s more, believed what the Bible declares as true regarding the shape of the Earth. Surely, we are being lied to—by everyone. Every kingdom, including North Korea; Iran; China; Russia; Israel; and our very own, the United States of America; are operated and managed by Satan. The Bible does not disagree. NASA is most certainly operated and managed by Satan. It exists as an entity of the Executive branch of government. But then let us not forget the Democrats; and the Republicans. Hollywood is Satan’s dominion. Nashville is Satan’s dominion. The Boy Scouts of America probably is too. There are 192 nations currently under the UN, by my count. They also are operated and managed by Satan—every one of them.

Our Messiah Yeshua wouldn’t bend a knee for a single claim to fame from any of them. He did not defeat Satan by running for government. He crushed his head on the cross, and by His blood he has snatched us away from the kingdom of darkness. His kingdom is not of this world—yet. So why must ours? Where is the outrage? Where is the—dare I say it—Satanic Panic? Get out of Babylon!

Spielberg’s highest ambition for the movie, he told TZ: “I would hope the film would encourage interests from off the planet to come visit us someday. That would be nice—and very rewarding.” But knowing what we do of the little garden gnome and his kind, we’re already being tended to. He touched Elliott’s forehead, writes Kotzwinkle. “I’ll be right here,” he said, fingertip glowing. The last line of Kotzwinkle’s narrative reads:

He went into the misty light, with his geranium.

Noel