Beaten & Bruised Between the Applauding Hands of the Higher Critic | “Gap Theory”— a Fatal Compromise

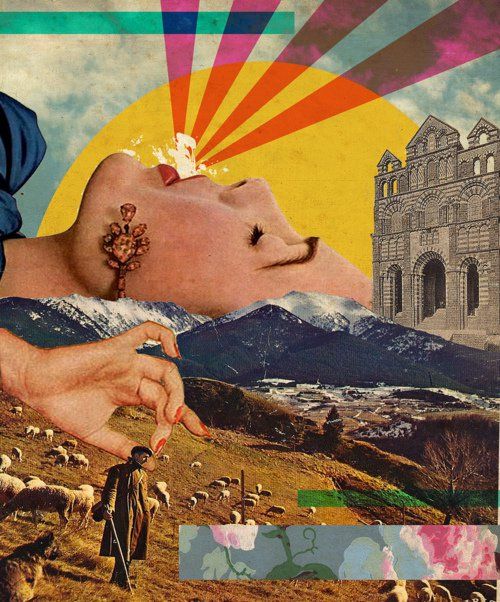

GIVEN ENOUGH TIME, ALMOST ANYTHING IS POSSIBLE. It was 1785, and the Enlightenment was not yet through, because Englishman James Hutton had one more treatise to contribute to its garbage heap of humanism. With Theory of the Earth, the age of creation became an issue of antiquity. History would no longer exemplify a six-thousand years old narrative—oh no. Quite suddenly, there were millions of years which needed accounting for. We should not be surprised to find that the high critics of academia met Hutton’s treatise with thunderous applaud. Hutton disfavored the Bible. And like most behemoth lies, he had peppered his theory in such a way as to make his observations seem strictly based on scientific knowledge rather than philosophical speculation. From the pulpit to the pews, panic ensued. The church had only recently forsaken the pleas of Martin Luther and settled into the Copernican Revolution—which he outright opposed—in hopes of harmonizing faith with higher criticism. Once again, Christianity was no longer immutable. Something else had to give. You know what they say. “The road to hell is paved with good intention.” Good intention and compromises.

Less than a decade earlier, French cosmologist and naturalist Comte de Buffon had already attempted to lift Science from the hinges of Biblical authority with his publication of Les époques de la nature in 1778. Before the 19th-century, Christians universally ascribed to a 6,000 year-old creation and a catastrophic flood, which not only gave the Earth’s features its observable contour, but preserved the totality of God’s created order. Buffon’s theory of extinction fell on deaf ears. So too did his imaginative storytelling, which employed the new physics of Newton as his springboard and sought to hypothesis how matter in motion might have formed the Earth. “The father of all thought in natural history” accredited the planets of the Copernican Universe as having been created by a comet’s catastrophic collision with the sun.

The snubbing he received—one might conjecture—can best be attributed to the fact that a war was presently being waged over the New World. And besides, Buffon was not loved by Americans. After propounding a theory that the New World and its inhabitants—including plants and animals—were inferior to Eurasia in all facets, going so far as to accredit its inferiority to “marsh odors,” an incensed Thomas Jefferson dispatched twenty soldiers to New Hampshire with explicit orders to capture a bull moose as proof of the “stature and majesty of American quadrupeds.” Buffon later admitted his error. Unfortunately, an even grosser transgression was committed. His comet theory, which posited the age of the earth to be 75,000 years old, was based on calculated figures which projected the cooling rate of iron. His attempt was a success—somewhat. Though the comet theory itself was not admitted, the age-old Universe which accommodated the error remained. Science was determined to come up with something—prove anything—which might give credence to their undeveloped religion.

French naturalist and zoologist George Cuvier came to Buffon’s rescue. As the “founding father of paleontology,” Cuvier was praised for his capability to work with a few bone fragments and reconstruct the complete anatomy of previously unknown species “with uncanny accuracy”—a practice which paleontologists would quickly make a habit of. While studying elephant fossils discovered near Paris, Cuvier demonstrated that their bones could not be paired up with their living African and Asian counterparts. They were provably distinct even from fossils in Siberia. In 1789 Cuvier published a treatise detailing the differences between the lower jaws of a mammoth and an Indian elephant. When a counter theory was proposed—that living members of these fossils still lurked somewhere on Earth, unrecognized—Cuvier scoffed. Extinction happened. For the Christian, this was a nagging problem which seemed to plague God of His divine plan. The saving faith may still have held the higher ground, culturally speaking, but its gates were being battered down. If Science was winning the war, it’s only because most combatants wanted favor with the mob. And besides, compromise is the cheapest lawyer.

Christianity’s unfulfilled need, particularly acknowledgement from higher criticism, is indeed unfortunate. In the most merciful of death blows, Cuvier threw them a bone. He suggested that there may have been a series of great floods throughout the undocumented and ever-elongated epochs of antiquity which wiped out any possible number of civilizations and species—all of which happened before the creation described in Genesis 1:1. In part, the church could keep to their 6,000-year theology, while simultaneously new doctrines were born.

Before Cuvier there is no historical record of a Christian anywhere advocating an age-old approach to creation. Famed theologian Thomas Chalmers, founder of the Free Church of Scotland, took it upon himself to save the church from spectacle. “One has only to read the writings of this man to understand how acutely he felt the attacks of science, and geology in particular, upon the Scriptures,” writes Weston Fields in Unformed and Unfilled (1976). He was “part of the age during which men were breaking loose from and thrusting aside what they felt had been the shackles of the Scriptures, and were placing all their hopes in the new science and its “assured” results. It is not without significance that Chalmers deemed it necessary to harmonize the Scriptures and science in order to save Christianity from the onslaught of atheism!”

During a sermon to his congregation in 1804, Thomas Chalmers brought the Gap Theory into being. According to Chalmers—the world existing between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2 was destroyed before its recreation in the six literal days described by Moses. With Science as their framework, they bought it. His views reached an even wider audience ten years later when in 1814 he wrote a review of Cuvier’s theory. Between Genesis 1:1 and 1:2, the Christian now had any number of years—billions if need be—in which he could agree to the fantastical pre-recorded fantasies of the Science religion. God apparently had more savory dishes to offer humanity through Natural Revelation.

Chalmers later wrote of Genesis 1:1: “My own opinion, as published in 1814, is that it forms no part of the first day— but refers to a period of indefinite antiquity when God created the worlds out of nothing. The commencement of the first day’s work I hold to be the moving of God’s Spirit upon the face of the waters. We can allow geology the amplest time . . . without infringing even on the literalities of the Mosaic record. . . .”

With Earth’s Earliest Ages, first published in 1884, G. H. Pember perhaps best outlined Gap thinking, and certainly attempted to qualify it, when he wrote: “It is thus clear that the second verse of Genesis describes the earth as a ruin; but there is no hint of the time which elapsed between creation and this ruin. Age after age may have rolled away, and it was probably during their course that the strata of the earth’s crust were gradually developed. Hence we see that geological attacks upon the Scriptures are altogether wide of the mark, are a mere beating of the air. There is room for any length of time between the first and second verses of the Bible. And again; since we have no inspired account of the geological formations, we are at liberty to believe that they were developed just in the order in which we find them. The whole process took place in preadamite times, in connection, perhaps, with another race of beings, and, consequently, does not at present concern us.”

It was a happy ending—sort of—well, not really.

One compromise gave way to another accommodation, and yet another… and another… and another. By the 1820s, Reverend John Fleming argued for a Noachian deluge which was perhaps not quite so catastrophic as Moses records, and in the decade to follow the evangelical Congregationalist theologian John Pye Smith advocated a local creation account and quite similarly a local flood, both of which occurred in Mesopotamia. Anglican clergyman and Oxford geometry professor Baden Powell went even further. He argued that Genesis was a myth simply intended to convey theological and moral truths. Hugh Miller, a prominent Scottish geologist and evangelical friend of Chalmers, abandoned his friend’s gap theory in favor of the day-age theory, which dismissed a week-long creation for days which represented entire ages. Miller came to this conclusion and shortly thereafter committed suicide.

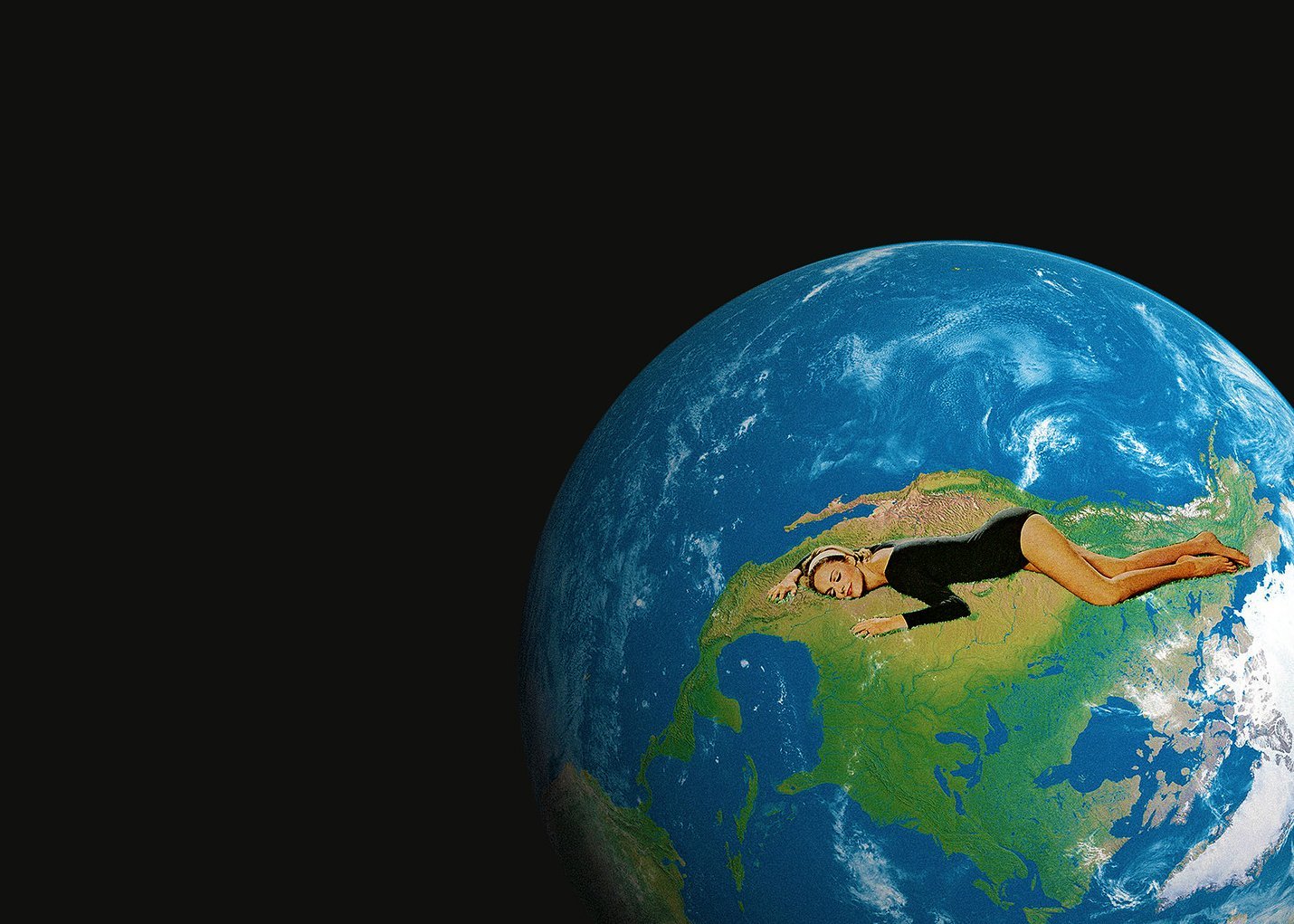

Charles Lyell made Hutton’s contempt for the Bible look elementary in comparison. As a contemporary of Thomas Chalmers and a man “of superior talent who thought” for himself and was “not blinded by (Scriptural) authority,” Lyell’s soaring ambition was to “free the sciences from Moses.” With Principles of Geology, first published in 1830, he did just that. Throughout its indignant pages Lyell refers to Scripture as “false conclusions… futile reasoning… founded on religious prejudices… ancient doctrines sanctioned by the implicit faith of many generations, and supposed to rest on scriptural authority.” Basing his work in part on Hutton, Buffon, and Cuvier, Lyell imagined other possibilities. He suggested the best way to account for the age of the Earth was through present observable processes in topography, a process which, he said, had been building very gradually at the same rate over vast amounts of time. He then divided stratum into layers and assigned each one an increasingly-deepening age. The ever-expanding chapters of pre-recorded history finally had names, so that on top of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic Ages is the Cenozoic—the spinning, whirling globe we currently stand upon.

Charles Lyell invented the geologic column.

Lyell’s creative storytelling became Scientific doctrine in 1830, long before carbon dating, potassium argon dating, and rubidium strontium dating could account for it. Then again, when carbon dating, potassium argon dating, and rubidium strontium dating were finally invented, Lyell not only dethroned Moses, as was his claim, but stood in the lawgivers place. How Lyell’s imaginations could be so precise, down to the fine print—we must conclude—could only come from Divine inspiration. But Lyell didn’t believe in that sort of thing.

Martin Luther was right. He once implored the brethren:

“We Christians must be different from the philosophers (scientists) in the way we think about the causes of these things. And if some are beyond our comprehension (like those before us concerning the waters above the heavens), we must believe them and admit our lack of knowledge rather than either wickedly deny them or presumptuously interpret them in conformity with our understanding.”

Little did Scottish theologian Thomas Chalmers suspect that harmonization with Natural Revelation was about as complimentary with Christianity as the roof of a house is on fire. Ultimately, Chalmers served the very evil which he supposed to prevent. Indeed unfortunate—it was a wholly avoidable disaster. And yet in hindsight Weston Fields sympathetically writes: “he could not have realized the full implications of his position” when Chalmers wrote:

“Should, in particular, the explanation that we now offer be sustained, this would permit an indefinite scope to the conjectures of geology—and without any undue liberty with the first chapter of Genesis.”

As it is with all great deceptions, man needs time—and more time. He needs time a-plenty if his perverse imaginations can coax his contemporaries away from the guiding light which only Scripture can provide in hopes of delivering counter promises. First the church knelt down to the astronomer—then the geologist—and finally the biologist. The set-up was perfectly executed. Charles Swindoll once said, “The swift wind of compromise is a lot more devastating than the sudden jolt of misfortune.” In actuality, all hell broke loose.

The church was ill-prepared for Mr. Charles Darwin.

Noel