Robert Frost: “In the Clearing” (a Review for the Copernican Revolution)

A MANIFEST Destiny of the Copernican nature was finally pressed upon and dutifully commissioned by President John F. Kennedy when he inspired his nation with the following decree:

“We set sail on this new sea because there is new knowledge to be gained, and new rights to be won, and they must be won and used for the progress of all people!”

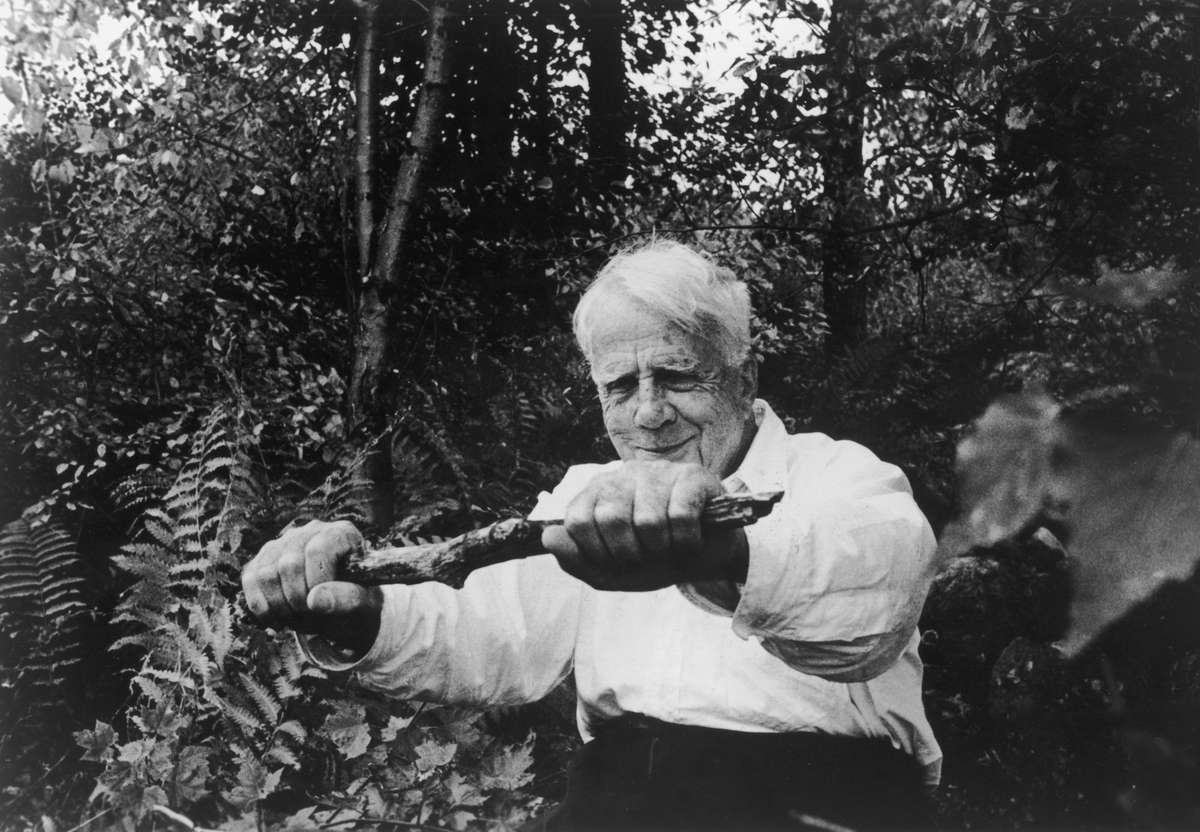

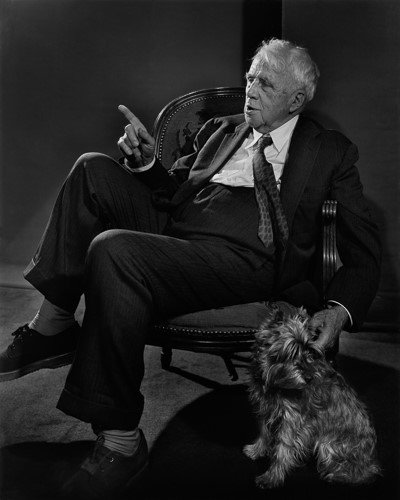

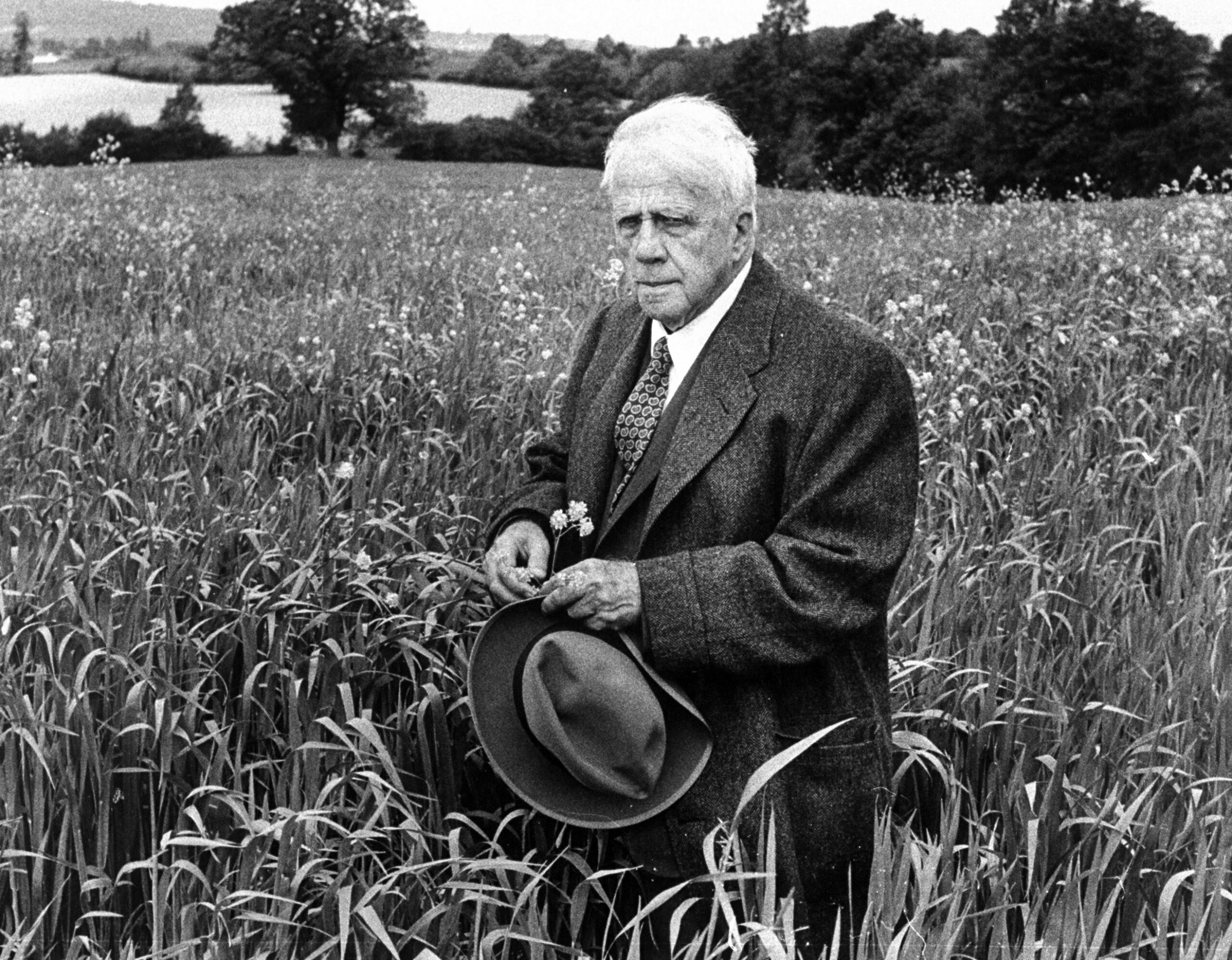

The year was 1962. Though most cleverly masked with the modernity of 20th-century Scientism, an undeniable religious fervor (as antiquated as the worthless mysteries of heaven which had been offered up during the first incursion) had been set ablaze in the hearts of every man. Kennedy had a way of doing that. This was 1962. Space race. Gone was the ancient cosmology—but not completely forgotten. The poet laureate of Vermont remembered. Before the decade came to a close, the life-giving idol television would redefine Scripture by ceremoniously imprinting two pairs of Freemason’s shoes on the moon. Robert Frost wouldn’t live to see it.

Throughout the Second World War, Frost refused any contribution of his words should they fuel allied propaganda, despite insistence from colleagues and friends that his poetry help in the effort. And yet, in the closing months of his life, having already celebrated Kennedy at the inauguration podium in 1961, Frost finally took up the commentators’ task with his pen. The winds had changed. Not even Frost could deny it. But rather than finding praise in Cold War espionage, the old farmer aptly and altogether dismissed its politics.

Throughout the Second World War, Frost refused any contribution of his words should they fuel allied propaganda, despite insistence from colleagues and friends that his poetry help in the effort. And yet, in the closing months of his life, having already celebrated Kennedy at the inauguration podium in 1961, Frost finally took up the commentators’ task with his pen. The winds had changed. Not even Frost could deny it. But rather than finding praise in Cold War espionage, the old farmer aptly and altogether dismissed its politics.

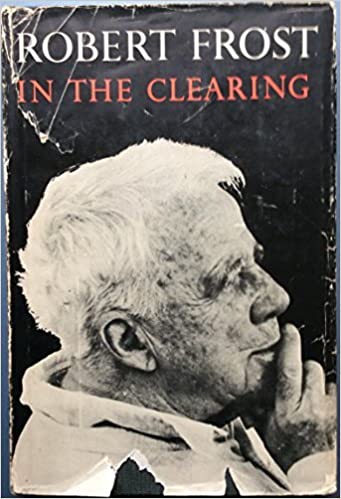

‘In the Clearing,’ which consisted of somewhere around forty of Frost’s lesser-known poems, was published on his 88th birthday. March 26, 1962. It would prove his final publication before his death. To his colleagues, America’s beloved poet simply came across as an old fuddy-duddy. By rejecting Scientism, thereby preferring the road less trodden upon, the apple picker had become a dissenter—even against the American dream, which relished now in the conquest of heaven.

Or perhaps more precisely—to be fair—the very readership which had once given praise to his metaphysical duality and cosmological simplicity had, almost overnight, suddenly outgrown him.

.

I FIRST wrote this paper on Robert Frost back in 2017. Every so often someone comments about how it affected them, but that is a rarity. In reality, very few have read it, and I’m okay with that. I consider it one of my deep tracks. A hidden gem for my most devoted of readers. Not everything I do will be printed out and held up by phallus-shaped magnets on some fridge in the break room at Langley, nor can they all make Big Daddy proud. Ever since publishing the paper I’ve thought about the New England poet, often to ask myself: “How do you even go about becoming the biggest contributor to American poetry?” You would think talent blended with a varied recipe of philosophical ingredients would have everything to do with it, and maybe living in a light house—but no. All those years I sat under a peer were apparently wasted. Turns out, the sons of Cain like to promote their own. Frost reading at Kennedy’s inauguration wasn’t a fluke. It’s all about genealogy. He was even more royal than the President.

Before dusting off this paper I decided to climb a ladder into Frost’s family tree, and wouldn’t you know it, I counted as many as 11 Magna Carta Sureties in his parentage. That can only mean one thing. Frost was a thorough breed. Follow along. His 20th great-grandfather was Robert de Ros. 21st great-grandfathers include Hugh le Bigod, William d’Aubeney, John de Lacy, Gilbert de Clare, and William de Mowbray. 22nd great-grandfathers include Richard de Clare, Saher de Quincy, Roger le Bigod, and Henry de Bohun. His 23rd great-grandfather is William de Huntingfield. As an added bonus, Robert Fitz Walter is a 19th great-granduncle.

His list of monarchs makes up the usual suspects. King Edward I of England is his 19th great-grandfather. King Henry III of England, 20th great-grandfather. King Louis VI of France, 24th great-grandfather. William the Conqueror of England, 25th great-grandfather. King Robert I of France, 29th great-grandfather. Alfred the Great, 31st great-grandfather. Last but certainly not least, Charlemagne, 33rd great-grandfather. Robert Frost is a son of Cain. Search your feelings, you know it to be true.

BUT getting back to In the Clearing, Frost’s final publication. In “A Concept Self-Conceived,” the old farmer did not shy when he wrote:

“The latest creed that has to be believed

And entered in our childish catechism

Is that the All’s a concept self-conceived,

Which is no more than good old Pantheism.”

Oh dear. Are we being fed another spoonful of Neoplatonism? Sounds Athenian, at any rate. I guess you can oppose the space narrative and still be a card-carrying member of Club Cain, so long as you push Plato like one needs a toilet paper product. At any rate, if traditional thoughts should hinder the progress of man, then the religion of Scientism will see to it that Elohim is nothing more than an evolutionary construct of our depraved imaginations. Did I get that right? And what’s worse, this “latest creed” has “entered our childish catechism.” For Frost, there is human “fact,” and then there is “divine” fact. Should the first pounce upon the second, or Yah forbid, indoctrinate and endanger the minds of children, then the conclusion is simple.

Frost retorts:

“The rule is, never give a child a choice.”

Harsh words. Elsewhere, “Lines Written in Dejection on the Eve of Great Success,” hearkens back thematically to one of his earlier poems, “Birches.” It was originally released during the outbreak of the First World War, and recalls the poet wishing he might climb a tree as he once managed in his childhood, all so that the rational world might be left behind. But now with Lines Written in Dejection, Frost is a tired old man, having first survived one World War and then another. Though the New World Order presses onward without him, he has yet to see their new man-made religion outmatch the beauty of untarnished imagination planted firmly in the soil and gazing skyward, a worldview which can only be gifted by the Divine. While Science may claim to land man on the moon, it will never catch the cow’s tail. After all, did Frost not once witness a cow jump over the moon? Indeed, he did. To this realization he sighs:

“That was back in the days of my Grandmother Goose.”

That might have something to do with the fact that his pupilage under Grandmother Goose included a cosmological view quite unfamiliar with our own. And it is this. The earth is flat.

Even today the sun and the moon still rise while the Earth stands still. Polaris remains permanently fixed in place while the luminaries play their part in the merry-go-round parade, endlessly carousing around our central point of light. The constellations within, which gave picturesque realities to the ancient man of “less fortunate times,” as the Copernican blindly believes (apparently “not knowing better” for lack of telescopes and television) refuse to change even now for the modern man. How odd. Water remains level. And quite similarly, the horizon always rises—no matter how high we climb—as if to mock the very notion of a globe.

We are told of course by our television—and also today by the Intel-net—that everything we experience with our own eyes is an illusion. To this I firmly plant my foot down in the soil. The old religion, which was based on God’s own Testimony and further counseled through our common senses, must be cast down to make way for the new. So says the Copernican. For this incursion—the out with the old in with the new attitude—Frost again retorts:

Once I was fool enough to think

That brains and sweetbreads were the same,

Till I was caught and put to shame,

First by a butcher, then a cook,

Then by a scientific book.

But ‘twas by making sweetbreads do

I passed with such a high I.Q.

.

Quandary

The pervasive nature of Scientism, being ultimately materialistic and technologically driven, is at best an artificial vision. It is nothing more than a shadow Universe. Because we can only experience the Copernican revolution by the chalk equations of a few academic Gnostic’s, or perhaps more practically, through the governments’ own programming services—the Intel-net and the television. Rides like Star Tours. It is quite impossible to partake in the fundamentals of such Sciences without first turning our gaze away from the realities with which Elohim has chosen to surround us with. The man who agrees to go along with an augmented reality must do so through a self-effacing, materialistic-driven, and quantitative standard of truth. He must therefore alienate himself. Technology thrives on weaning a man off reality. And worse, he endangers estranging himself from the Most-High.

The sun rises in the east and sets in the west. The very notion that the world turns in place of the sun goes against our every real human experience. To reject this reality drives the evil needed for our own dismissal of Elohim’s revelation even deeper. Despite reported black holes, satellites, distant nebula’s, and an unmentionable number of uninhabitable planets, the old-world view is still present and accounted for in our peripheral vision, if only we should shut off the technological means which seek to callous and pervert the human experience. Truth in plane/plain sight.

Frost mourns this augmented experience in “[Four-Room Shack…],” yet another cranky old man poem describing Sciences contempt of those real Elohim-given experiences in favor of a television (as in, the “four-room shack”), complete with “visions in the sky” and bunny-eared antennae serving for its “scrawny mast.”

“Four-room shack aspiring high

With an arm of scrawny mast

For the visions in the sky

That go blindly pouring past.

In the ear and in the eye

What you get is what to buy.

Hope you’re satisfied to last.”

Society’s trust in another reality, conveniently hid behind a curtain is troublesome to say the least. Indeed, by the end of his life, Robert Frost was a dissenter. In yet another cranky old man poem, he even scoffs at the notion of participating in a contradictory worldview beyond our own day-to-day functions. Appropriately titled “Some Science Fiction,” Frost quips:

“They may end by banishing me

To the penal colony

They are thinking of pretty soon

Establishing on the moon.”

He even goes so far as to mock man’s gullibility, if he should actually believe a scenario might arise where the poor farmer from Vermont might be banished to up-and-coming colony on the moon, claiming:

“With a can of condensed air

I could go almost anywhere,

Or rather submit to be sent

As a noble experiment.”

Frost’s criticism trudges on with “Wishing Well.” Mankind continuously showcases a rather obstinate treatment towards the Divine Creator. This was particularly made known in his own life with the space race. Here the poet revels in picturesque Biblical cosmology by invoking the firmament (raqia in Hebrew). That solid dome boldly acting as a barrier between Earth and the so-called “space,” which both NASA and the Soviets were purporting to explore. He says:

“It merely would entail the purge

That the just-pausing Demiurge

Asks of himself once in so often

So the firm firmament won’t soften.”

Frost apparently knew the function of the firmament better than almost anyone living today, even if he did settle on mythological origins. After all, the poet makes no claim to Scripture. At any rate, the firmament of Noah’s day even now withholds the waters which once drowned every living soul with the breath of life, save for those on the ark, in a worldwide flood. Noting the firmaments ties to this account, he naturally adds:

“There’s always been an Ararat

Where someone someone else begat

To start the world all over at.”

For all I know, Robert Frost was in on the deception. Who the hell knows? I mean, the guy was related to nearly every President and even King Henry VIII’s wives. Nor do we find any reason to doubt his allegiance towards Spherical Earth. Yet being born only nine years after Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, his was a generation which ought to have known better. We’ll call it false memory syndrome, for sake of argument. The space race likely conflicted with his own memories, and his full catalog of poetry certainly shows that to be the case. Indeed, conflicts of opinion—where the shape of the Earth was concerned—were publicly aroused in Frost’s younger years. This is a documented fact. And despite the new Copernican “morality,” which tugged dutifully at the heart of almost every American, there were some who kept to their better senses. Not everyone succumbed to the demands of the Scientific religious, even if they became the shrunken minority of opinion.

Presently, we are those whom Frost frightfully spoke of when he wrote: “The latest creed that has to be believed entered in our childish catechism.” That is us. We are the generation which has—well, a select few of us at least—-turned our gaze from the repulsive “four-room shack” with an “arm of scrawny mast” that has attempted to bewitch us with “visions in the sky.” Those few of us ha

ve been so fortunate to see the moon as the cranky old farmer from Vermont once perceived it; a luminary more likely to sponsor a cow leaping over its dish-like rim rather than Freemasons bobbing in slow-motion across its dark face.

Whatever his cosmological conclusions, Frost’s disdain for any further exploration within the perceived realities of the Copernican Universe, and the devastating personal alienation which belief in such a technocratic society would cause, couldn’t have become any more transparent than the 19 words which made up one of his life’s closing poems, “[But Outer Space…]” in which he writes:

“But outer Space,

At least this far,

For all the fuss

Of the populace

Stays more popular

Than populous.”

Noel

.