Flat Earthist Charles Johnson vs. the Late Great Planet Earth

1

SAMUEL SHENTON WAS DEAD.

It was 1972, and as the crew of the Apollo 17 readied to photograph the Blue Marble on NASA’s final moon mission, Lillian was faced with the prospect of what to do with her late husband’s work. Stacks of books and papers and boxes, undoubtedly chaotic with correspondences, remained. Without Shenton—or rather, without another Shenton to fill his shoes; nobody seemed to have any hope of knowing the true shape of the earth they were standing on. The IFERS had dwindled to a handful of members, and not even its own president, Ellis Hillman, a Greater London council member, believed the earth to be flat. For Hillman, ancient cosmology was merely an interesting idea, something he might even go on talking about in his spare time. And besides, he’d read all about Zetetic astronomy in the British Library. Lack of enthusiasm aside, he alone was Shenton’s natural successor—this, according to Hillman. Despite the ridicule which Shenton was forced to endure, the politician had nuzzled up to him and served faithfully at his side. Therefore, nobody else had a right to his lifetime collection of work but him.

Halfway across the face of the earth, in San Francisco, California, a certain forty-eight year-old Charles Johnson, who had corresponded with Shenton for nearly a decade and remained an enthusiastic IFERS member in doing so, hoped to relieve Lillian of the burden. Despite not being a sign maker, as Shenton was, he felt a nudge, a prod, a higher calling to Shenton’s public profession. Johnson contended that Hillman exhibited a lack of conviction—and rightly so. Hillman was also president of the Lewis Carroll Society, re-established in 1969. As an advocate for Carroll’s legacy, Hillman would give amusing lectures on the flat earth concept, perhaps as a way to combine his newfound whimsical nonsense humor, as though Wonderland and Shenton’s earth were confused. It is an activity however, perhaps more of a side hobby, which the politician would not bother himself with more than twice a year, despite frequent requests.

In a stunning move, Ellis Hillman borrowed a van, showed up at Lillian’s Dover house, and transported the bulk of Shenton’s papers, whatever he could get his hands on (and apparently for her convenience), to the archive department of the North East London Polytechnic. He would later claim that he had arrived precisely in time to prevent Shenton’s widow from disposing of his work in a rubbish bin outside of their home.

Crisis diverted.

Adding insult to injury, Shenton’s papers were thereafter secluded for safekeeping in cardboard boxes, shipped to the archives of the Science Fiction Foundation in Barking, a district and suburban area of East London—which, no surprise, Hillman had also helped to found.

To his dying day in 1996, Hillman insisted that the flat earthist Charles Johnson, whom he’d plotted to wrestle Shenton’s legacy from, was a serious nutter.

2

CHARLIE BROWN FIRST LEARNED ABOUT planet Earth as most of us did—in the classroom. The date was October 27, 1950, only three weeks after Peanuts first premiered, and Shermy’s claim that a schoolroom globe is “proof” of its spherical nature did not pass by Brown without an initial air of skepticism. But where apprehension is concerned, Charles Kenneth Johnson’s introduction to the schoolroom globe was carried out in a slightly more dramatic fashion. Born on his father’s cattle ranch in Tennyson, Texas, on July 24, 1924, only two years after Schulz, Johnson would never forget the day when, in the second or third grade, his teacher introduced them to the very thing.

“Now they brought out this globe,” he later recalled. “It wasn’t like today, they didn’t have globes everywhere, and people didn’t say globe every few minutes. They put out this globe, and started the propaganda on it. I didn’t accept it from the start. You can see the thing is false! It’s quite obvious. I can see it today the same as I saw it there.”

A ball with water on it—and the water just hangs there? The eight year-old thought. Why don’t ships sail over the edge and fall off?

He then spoke his concerns out loud. His teacher immediately and publicly rebuffed his concerns. But Charles Kenneth insisted. Mam, this is a sham. The boy was sent home from school with an added homework assignment. He was to fetch a bucket, fill it with water, swing it round and observe the centrifugal force which held the water in place, as Newtonian laws of motion implied.

Not a single moment was wasted. Here Johnson further recalled: “I got a bucket of water and I whirled it around. It didn’t come out, but I saw at the same time that it had nothing to do with the globe. This was absurd. So I knew there was a lie here. Maybe I was extra smart or extra something for my age. I see other things they told us in school weren’t true. But that was the big one. I knew it and I’ve always known it. It’s a complete world of lies, telling you things they know when they really don’t know it. I always knew that the Earth was not a ball. I pondered for a while about how I could prove otherwise, but I didn’t want to spend any time dwelling on it. I just knew that the Earth was flat.”

He later told a Chicago Tribune reporter, “The water was rigid in the bucket. It wasn’t moving, like people, cars, trucks, trains, and animals do.”

By May 11, 1957, some seven years after Charlie Brown’s initial introduction, Brown was thoroughly indoctrinated—though apparently glum about it, as one would expect of America’s favorite block-head. Lucy however had not passed the exam, because the thought of an Earth “spinning through space” was laughable at best—and reserved for one’s wildest imaginations.

“People come and people go, but the Earth keeps on spinning,” says Charlie Brown.

“Spinning?” Lucy asks from behind a stone wall. “What do you mean, spinning?”

“Spinning through space….” Charlie brown explains. “The Earth keeps on spinning through space.”

Lucy explodes into laughter: “Oh, my, Charlie Brown! You may not be the brightest person in the world, but you sure have some imagination!”

“Good grief!”

Charles Johnson, however, was never convinced. While his schoolmates learned about the globe and then fleshed out what imaginations a globular Earth offered on the playground, Johnson poured through library books, searching knowledge, desperately seeking answers—all the while striving to withstand the monotonous persuasions of his school regime. It was there in the library where he acquainted himself with Freud, Einstein, and Dickens on his own. As a pubescent, Johnson later quipped that he’d already acquired more knowledge than the average University graduate. And then one day the young Johnson happened upon an article in Harper’s Magazine concerning Zion’s overseer, Wilbur Glenn Voliva.

Again, Johnson recalled: “I knew in a split second, when I read in Harper’s Magazine, just check the water. I said, ‘My God! Why didn’t I think of that?’ I vowed that the minute I’d get to a lake, I’d check it. I knew from that second then how to prove it.”

The boy wrote the ailing Voliva a letter.

Voliva responded,

—and then he died. With Voliva finally buried (good riddance), the Utopian hopefuls of Zion, Illinois abandoned his teachings just as quickly, and with as much dramatic hand wiping, as Voliva had with Dowie. With the outbreak of the Second World War, particularly the atomic age to follow, flat earth was an embarrassment to almost everyone involved.

Charles Johnson would have to wait nearly another two decades before a certain Samuel Shenton of Dover, England, would take up the fight alone.

3

THE WORLD’S PREDILECTION FOR THE PHILOSOPHY of Greeks and Alexandrian delusion, an entire two millennia of it, must have been washed away in a deluge of rejuvenation that very moment after Charles Kenneth Johnson, then in his late twenties, entered a San Francisco record store in search of Acker Bilk’s evocative and haunting bestseller, Stranger on the Shore. Six months after hitting the top of the charts in England, the clarinet single, which had been written for Bilk’s daughter, topped the United States charts for seven consecutive weeks. In 1962 Billboard named it the number one single for the year.

Charles hoped to reach for a copy. Then again, Marjory did too.

Their fingers met, and the two strangers quickly discovered that they had far more in common than a taste in music. Charles was a vegetarian. Marjory was too. They even had geography in common. Both were flat earthists and single. Charles Johnson would often remind his critics that Marjory was shocked when she migrated with her family from Australia during the War and arrived in America to learn that her native home was referred to as the land down under. Marjory would argue otherwise. Ultimately, she swore in an affidavit that she had never once hung by her feet.

They were married in 1962 and honeymooned in Reno.

Despite the fact that Gene Cernan, a crew member onboard the Apollo 10, employed Stranger on the Shore as the soundtrack to their moon mission some seven years after their meeting, playing it on cassette tape from the command module, nothing—not even NASA—could ruin their song.

4

LILLIAN DID MANAGE TO KEEP ENOUGH of her late husband’s original collection at arm’s length from Hillman’s rubbish rescue to ship whatever remained, a mere package it seems, to Johnson in San Francisco. Johnson, who had served up until now as an aero-plane mechanic for twenty-five years, was grief-stricken to learn that Shenton’s life work had been entered into the science-fiction genre under the watchful eye of a politician, but with Lillian’s gift, albeit a modest one, the hopeful heir was elated. He later recollected experiencing “a great surge of feeling” upon receiving the package, finally holding Shenton’s own handwritten notes between his fingertips. At that very moment, Johnson later recalled: “I knew what all my life had been for, what all the experiences I’ve had are for.”

Everything had been, he said, “to prepare me for now!”

This generation… This very moment…

It was God’s calling.

For Johnson, holding Shenton’s torch, in accordance with Samuel and Lillian’s blessing no less, was akin to receiving “the mantle of Elijah.” He and Marjory, Johnson insisted, were the very last iconoclasts.

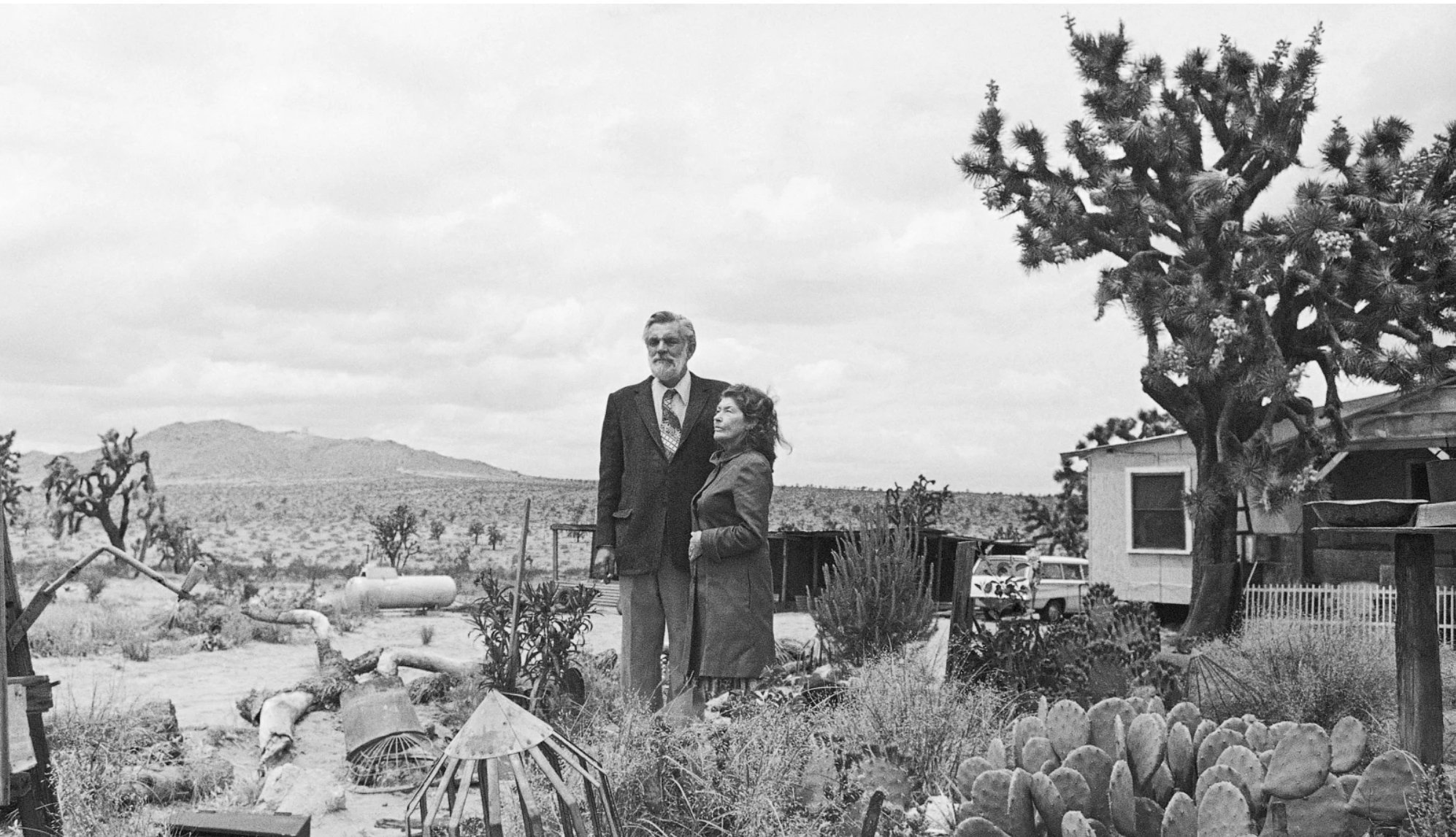

That very year, 1972, Johnson retired from his career in aircraft mechanics and incorporated Shenton’s organization as the International Flat Earth Research Society of America and Covenant People’s Church, aptly relocating to California’s Mojave Desert, where he purchased five acres of land, ‘God’s five acres’,’ he dubbed it, for a mere $10,000. Charles and Marjory would remain there for the rest of their lives.

5

THOUGH IT IS TRUE, LANCASTER HAS noticeably widened at its hips over the years, very little else of the Mojave Desert has changed from Charles Johnson’s time until now. It is here where California State Route 14, the vital artery which winds through Antelope Valley and in turn serves to connect the city with the exotic excesses of Los Angeles, can finally stretch out its legs with ease and continue through an almost endless horizon of jagged canyons and parched earth. I like to think of the flat earthist at the end of each day, wearily chomping down on a cigar from his front porch. Johnson is a distinguished-looking bearded gentleman who contrasts vegetarianism with a lifetime of chain-smoking, hand-rolling each cigarette with an air of professionality, and he drinks coffee by the pot. His legs are slightly elevated, feet folded together on a stool, as he gazes at the canvas of blazing color surrounding him—a routine sunset which only the desert can offer.

Twenty miles to his west, the Tehachepi Mountains rise up from the painted floor—a comfortable, practically fortified barrier separating him from the rich agriculture of Bakersfield and the San Joaquin Valley beyond. Twenty miles to his south, as the bird flies, is a notable curiosity piece known as Vasquez Rocks, site of various filming projects, mostly science-fiction due to its eerily twisted, alien-like features. TV production surrounds Johnson, including numerous episodes of the Twilight Zone. As a habit, alien landscapes tend to take on the familiar face of his own isolated world. Speaking of which, another twenty miles to the north, Johnson might look out as far as Edwards Air Force Base, the ancient lake-bed which will, over the decades, host the landing of 54 space shuttle missions and some change, as well as test their capabilities for orbit. A silhouette of Joshua trees, creosote bushes and tumbleweeds surround him, and in practically all directions, abandoned mine shafts and forsaken ghost towns litter the landscape. Lancaster is truly a world unto itself. Only from here can the Copernican universe expand forth within the immeasurable imaginations of men, with no firmament to contain them.

Pull any calendar year out of a hat, 1972 or the turn of the millennium, it matters little. The sunsets are conveniently the same, breathtaking, and memories of Charles Manson remain. The Johnson’s arrived in Lancaster only a year after the Tate murder trials concluded, and yet in the little mining ghost town of Ballarat, straddling the edges of something remotely habitable and Death Valley, a green-and-white truck employed by the Manson family still sits abandoned to this very day (pick any year between then and 2019), situated precisely where police apprehended its members after fleeing Barker Ranch in 1969. Time and scorched winds have slowly eaten bullet holes into its rusted metal, but pentagrams, spray painted silver on the inside of the truck, are not so easily scrubbed away. And if one looks especially close, he or she might even read three letters etched into its door, WAR.

From the world in which the flat earthist inhabits on his front porch, chomping away on an evening cigar, the Johnson home is a half-mile journey from the nearest neighbor. Friends drop by now and then, but his primary companions are several cats, half a dozen dogs, scatterbrained chickens, and the occasional desert tortoise or road runner—not forgetting the love of his life, Marjory. No electric-power line runs to the property; the world’s first and foremost flat earth headquarters; and water must be carried up the hill. But that’s how the Johnson’s like it, a complete isolation from globular society. “We’re two witnesses against the whole world,” Johnson once told a reporter. “We’ve chosen that path, but it isolates us from everyone. We’re not complaining. It has to be. But it does kind of get to you sometimes.” Then again, there are daily visits from the postman to consider. By 1980 his flow of letters will peak at around 2,000 a year; or a half-dozen every day—not all of which are properly addressed. But it matters little. Any mail addressed to the flat earth, the postal service knows to deliver.

I like to think of the irony encapsulating his peripheral vision over three intellectually tiresome decades as he lowers his cigar to sip on coffee over and over again, rinse and repeat, one evening after the next—though perhaps Marjory has brewed him decaf at this hour. If not for the various fantasy scripts fleshed out at Vasquez Rocks or Red Rock Canyon and the like, most notably the stand-in arena where Captain Kirk wrestled an extraterrestrial humanoid reptilian species, known as a Gorn, in a 1967 episode of Star Trek, then he has real life space shuttles to consider. Occasionally the sins of the outside world prod at him, as personified by the Manson’s and an uneasy marriage with the muddled narrative of an equally sinister media objective. For example, Manson family member Lynette Fromme’s attempt to assassinate U.S. President Gerald Ford in 1975 by simply pointing a gun at him has all the markings of a Manchurian candidate. Surely, Johnson thinks about that when considering those individuals and the truck which remains as a testimony to their plight from Baker Ranch.

As the sun sets over ‘God’s Five Acres,’ I can see Johnson now, the last iconoclast, cocking his head back, and precisely how Science Digest described him in 1980, with “a wry sense of humor and booming laugh,” cleverly chuckling at the madness which nuzzles the outside world with the warmth of a baby blanket of sorts and which simultaneously seeks to administer to his seclusion, sadistically beckoning him on, or perhaps it is only the aching groans of a windswept desert.

Clack—clack—clack—click—clack, goes his typewriter.

“Scientists consist of the same old gang of witch doctors, sorcerers, tellers of tales, the priest-entertainers for the common people,” he once perfectly summed up his entire worldview for Flat Earth News. “Science consists of a weird, way-out occult concoction of gibberish theory-theology unrelated to the real world of facts, technology and inventions, tall buildings, fast cars, aero planes and other real and good things in life.”

For the first decade of the Johnson’s Flat Earth Research Society, only 200 paying members, many of which consist of Voliva’s Zion residents, subscribe to his writings. As the decades roll on and the sun continually sets over the scorched desert of Lancaster, that number will rise and eventually cap off somewhere around 3,500, no doubt with help from the press, who love more than anything to peer in and jeer at him for the pleasure-reading of a self-flagellating audience.

Clack—clack—clack—click—clack.

Moses and the Prophets and Jesus and all His Disciples taught and knew the Earth was flat.

Clack—clack—clack—click—clack.

Witch doctors are attempting to replace that old time religion with Science.

Clack—clack—clack—click—clack.

Galileo, Newton, Martin Luther, Descartes, Darwin, Fake Space Program, COPERNICIOUS [sic] monstrosity! Now is the season of Satan…

Clack—clack—clack—click—clack.

The media often returns fire. If Americans are completely oblivious to the prophet in the wilderness, the media will not fail to let them know about it. In 1984 Newsweek will convey that Johnson’s Flat Earth Research Society is more “a mystical entity than an organization.” John Mitchell, 67th Attorney General of the United States under President Richard Nixon, basically says something of the equivalent to “I know you are but what am I?” when he lumps Johnson’s society with modern-day druidism.

“Whatever its purpose,” author Robert J. Schadewald writes in Worlds of Their Own: A Brief History of Misguided Ideas: Creationism, Flat Earthism, Energy Scams, and the Velikovsky Affair, regarding the Shuttles of Edwards Air Force Base, “Johnson is convinced that it is not intended to actually fly.” Schadewald seems to shrug, almost apathetically, as he further writes: “Perhaps the Space Shuttle is intended to bolster the beliefs of these backsliders. Whatever its purpose, Johnson is convinced that it is not intended to actually fly. Because it was build and tested almost in his back yard, he knows many people who worked on it. What they’ve told him about some aspects of its construction only reinforces his convictions.”

“They moved it across the field,” Johnson sneers for Schadewald, “and it almost fell apart. All those little side pieces are on with epoxy, and half fell off!”

Schadewald further explains, “The Shuttle had other problems besides heat resistant tiles that wouldn’t stick. For instance, when the testers tried to mount it on a 747 for its first piggy-back test flight, it wouldn’t fit.” “

Here Johnson chortles.

“Can you imagine that? Millions of dollars they spent, and it wouldn’t fit! They had to call in a handyman to drill some new holes to make the thing fit. Then they took it up in the air–and some more of it fell to pieces.”

The fact that the Shuttle will eventually, potentially, orbit on its own and then return to Edwards Air Force Base, Schadewald adds, is appropriate enough for the flat earthist.

“Do you know what they’re doing at Edwards right now?” he asks for the writer’s pleasure. “’Buck Rogers in the 25th Century’ is made right where they claim they’re going to land the Shuttle. Edwards is strictly a science-fiction base now. Buck is a much better science program, considerably more authentic. In fact, I recommend that the government get out of the space business and turn the whole thing over to ABC, CBS, and NBC. The TV networks do a far superior job. They could actually pay the government for rights, and it wouldn’t cost the taxpayers a penny.”

The wild popularity of Buck Rogers during the first half of the 20th century is likely lost to most millennial’s these days, but her counterpart isn’t. Star Wars, he will tell another reporter, was made in some guy’s garage.

Clack—clack—clack—click—clack.

That George fellow made an entire universe more believable than the U.S. government out here in Lancaster.

Clack—clack—clack—click—clack.

Most of all, I like to picture Johnson sitting on his porch, cigar in his fingertips, imagining what is still to come. Though he sees himself and Marjory as examples for society standing “way ahead of the pack,” it is only because he holds to long snubbed Biblical truths. And yet he dreams of something far larger than himself. Johnson is nothing. He is an old man in the desert exhibiting nothing more or less than a simple childlike faith. Long before the internet revolution Johnson dreams of a Zetetic research center. He dreams of a nationwide flat earth lecturing tour by RV. But he also dreams of a national flat earth convention, and just as importantly a chosen people to warm those seats, having collectively cracked the age-old puzzle. There’s simply no motion to the Earth—no curvature. It’s that simple. Surely, a generation is coming that can wrap their heads around those simplest and easiest to comprehend facts. Regardless, as the decades roll by, the aging couple slave tirelessly over a flat earth awakening which they will never live to see.

They will clap away at their typewriters each day, vainly searching without ever finding a successor. That somebody will come—in fact, an entire army of them; but none who likely read his work while they yet live.

I can picture Johnson now, watching the sun set on the secluded, paradoxical world he loves, and the dawn he patiently hopes to see—yet never will. Charles Johnson; with that wry sense of humor and booming laugh, thinking about Christopher Columbus, whom he swears until his dying day is a fellow flat earthist. And then Copernicus—he thinks about Copernicus, and then cracks a joke which only he alone can hear.

“Co-pernicious,” he calls him.

He clamps down on his evening cigar and laughs. Nobody else laughs along. And that’s okay. One day they will. The day is coming. Many will be chosen, hand-picked even, to believe the simplest and easiest to grasp of truths—they’ll have little to no choice—and then live within the Lancaster of their own mind. And then they’ll laugh along.

Say it with me.

Co-pernicious—

Noel

This article was a segment from THE UNEXPECTED COSMOLOGY: Rise of the 21st-Century Flat Earth Awakening, and is now on sale on Amazon and eBay.

Signed copies at Sacred Word Publishing: THE UNEXPECTED COSMOLOGY (1st edition signed)

Paperback copies on Amazon: THE UNEXPECTED COSMOLOGY (1st edition)

E-book copies on Amazon: THE UNEXPECTED COSMOLOGY