The Lion King: A Retelling of Platonism & the Mysteries of Isis

THERE IS A SCENE IN DISNEY’S THE LION KING in which Simba, Timon, and Pumbaa are lying on their backs, having nestled into a soft bed of grass, and presently gazing, with philosophically wonder, at the stars in the firmament above.

The warthog, they call him Mister Pig, asks Timon: “Timon, ever wonder what those sparkly dots are up there?”

The meerkat coolly responds: “Pumbaa, I don’t wonder. I know.”

Pumbaa shrugs: “Oh. What are they?”

“They’re fireflies,” says Timon. “Fireflies that, uh…got stuck up on that big bluish-black thing.”

Pumbaa shrugs, “Oh, gee. I always thought they were balls of gas burning billions of miles away.”

I seem to recall, being thirteen years of age when The Lion King was first released in June of 1994, that Pumbaa’s declaration garnished one of the audience’s largest howls of approval. Even I laughed along because, in a way, the logic was inverted. Though the warthog was apparently ignorant in the scope of his imaginative prowess, as globe earth Copernicans, we knew him to be right.

For added comic relief, Timon then exchanges one laugh for another.

“Pumbaa,” he sighs, “with you, everything’s gas.”

Insert laugh track….

“Simba, what do you think?” The warthog wants to know.

Simba sighs, “Well, I don’t know…”

His sigh is important. Simba does in fact have a varying opinion on the matter, and should we have been paying close attention, astrology fills in those gaps. Early on in the narrative, the cub has already been instructed by his father Mufasa regarding the legitimate identity and divine personhood of the stars.

“Simba,” Mufasa instructed his son, “Let me tell you something that my father told me. Look at the stars. The great kings of the past look down on us from those stars.”

His cub was intrigued, “Really?”

“Yes. So whenever you feel alone, just remember that those kings will always be there to guide you, and so will I.”

In 1994, Simba’s sigh immediately abreasted us with the need to clench our gut. As royalty, we know he has been taught hidden mysteries which the little people, the uninitiated, are not aware of. We know what he knows on the matter, but the question is, does he still believe? Culpability is a necessary recipe for his sigh. Simba is filled with guilt. He holds himself responsible for the death of his father. And rather than claiming accountability in such a way as to deal with the trauma, he has chosen to stump his own emotional maturity, despite taking on the biological markings of an adult. He has forsaken his moral obligation in favor of a carefree life. Hakuna Matata. That’s his philosophy, we are told. In Swahili, it means no worries. But you probably already knew that.

Still, Pumbaa wants to know. “Aw come on. Give, give, give…” he pleads. “Well, come on, Simba, we told you ours… pleeeease?”

Timon joins in with the plea.

Rather reluctantly, Simba says: “Well, somebody once told me that the great kings of the past are up there, watching over us.”

Pumbaa says, “Really?”

And then Timon, apparently trying to keep his composure, asks: “You mean a bunch of royal dead guys are watching us?” Timon immediately collapses into side-splitting laughter. Pumbaa joins in.

Simba does so too, but only half-heartedly.

“Who told you something like that? What mook made that up?”

Simba shrugs: “Yeah, pretty dumb, huh?”

But we recognize cinematic conflict when it is feed to us. This is 1994, and as audience members seated in that darkened theater, we share a common optimism. The applause solely belongs to Simba, even it he hasn’t earned it yet. If only Simba would not forget his true self. In typical Hollywood fashion, the reality truly is inverted. Pumbaa’s laughable agreement with the elementary-age textbook is in fact the punishable ignorance. If we cling to a single faith, it is in whimpered hopes that Mufasa’s worldview will conquer the east African dark—how can it not? Despite Simba’s sigh;despite his slumping off into the night; orthodoxy is about to be manifested. It is through a witch doctor named Rafiki—the word means friend in Swahili—in which Simba will receive a vision from the stars itself.

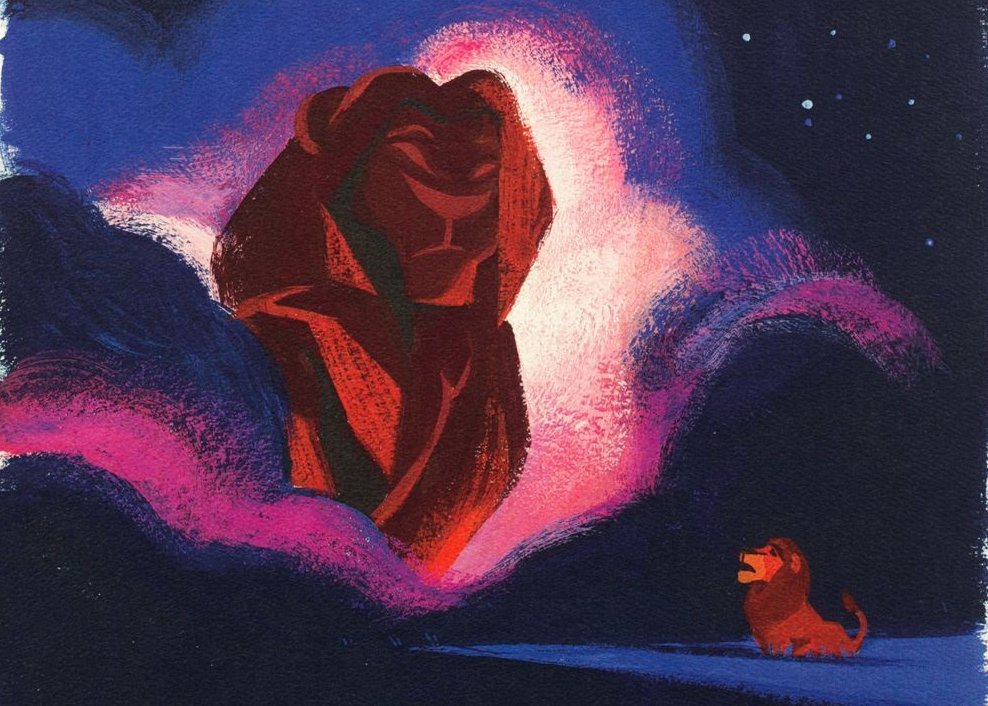

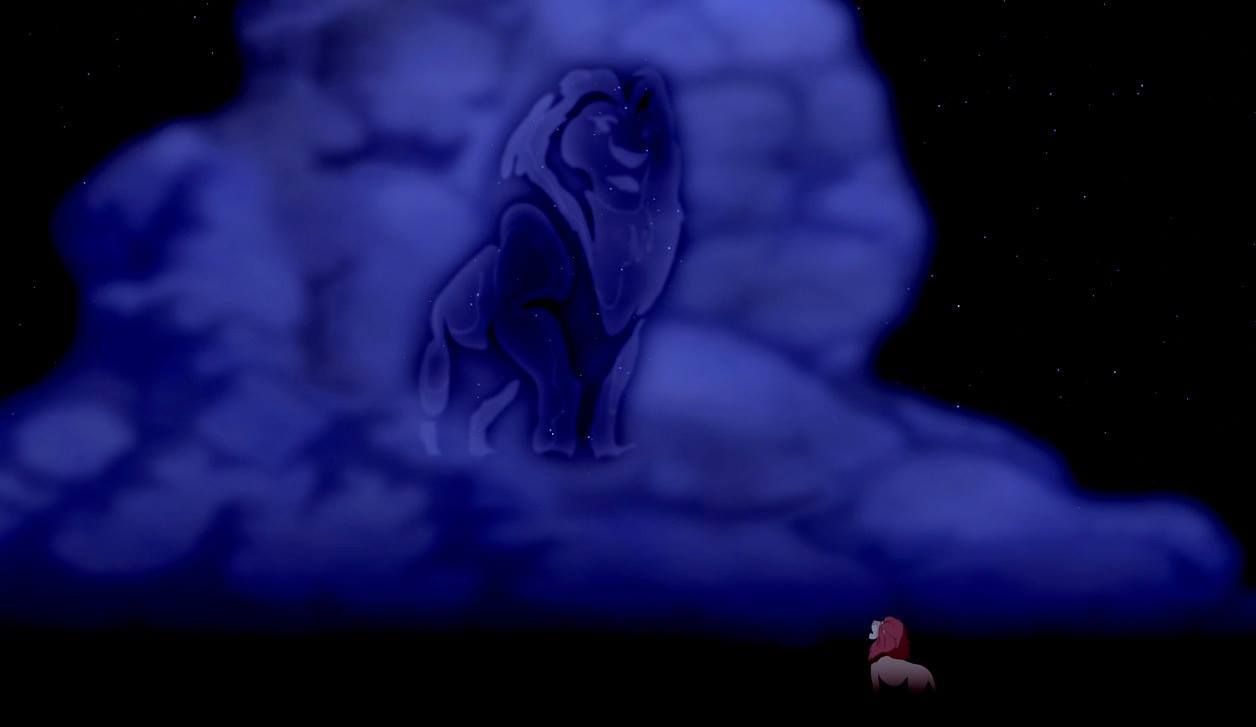

Simba beholds a god.

“Simba,” calls a familiar voice, “you have forgotten me.”

The blazing eyes… the fiery hair and crystalline complexion… And yet Simba does not stop to question the identity of the divine being in the stars.

“No, how could I?”

Mufasa explains: “You have forgotten who you are, and so forgotten me. Look inside yourself Simba, you are more than what you have become. You must take your place in the Circle of Life.”

“How can I go back? I’m not who I used to be.”

“Remember who you are. You are my son, and the one true King.”

Peculiar weather, the baboon quips.

Another joke. Insert laugh track. If the audience cackles, its likely because they know what the baboon has already long known—that Simba also is now in the know. In slightly other terms, he has been granted hidden knowledge. But more importantly to the turn of the tide, he has not disposed of nor fumbled it this time. Gnosis prompts action. And no king, whatever his lineage, may assert his claim to the throne without it. What the audience likely doesn’t realize however is that Simba’s initiation eerily depicts the very sort of vision which filled crypt-like catacombs throughout the Mysteries of Mithras. His father, in a way, personifies Mithras himself.

It is a scene directly out of Plato’s Timaeus.

For Plato, individual adepts could find immortality through initiation and transformation. Essential to this were the stars. Specifically to Timaeus, each soul was connected with its own star, one which he or she would return to after death. This is why Plato believed all knowledge was nothing more than a recollection of our previous existence in the spiritual realm of perfect forms, critical truths which are aptly forgotten and likely corrupted in this present world of matter. A century later, the Turkish-born Greek philosopher Heraclides Ponticus (387-312) identified the Milky Way as the path on which the souls ascended and descended—hence the thick concentration of stars. He wrote, “The great Plato had comparatively recently insisted that while our fallen, corruptible world may be analyzable using rationality, the really pure, uncontaminated cosmic bodies were to be found in the skies, or rather the heavens. Here were the seats of pure spirituality, divine beings if you like.” The early twentieth-century scholar Franz Cumont would refer to this religion as “celestial immortality,” or “sidereal eschatology.”

Platonism, and the Mysteries which the Patriarch of Greek philosophy derived his intellectual inquiry from, as well, rather ironically, as the clockwork occulting wisdom which emerged from his water well, monopolizes The Lion King’s entire weltanschauung. If Pumbaa’s imaginative conclusions were accurate, then the entire script would be capsized.

Consider that Simba had braved his own demise by entering into the confines of death itself; the only land void of light—the elephant graveyard. Surely, he would have been killed by its inhabitants, the hyenas, had it not been for the intervention of his father. Every episode of Simba’s life lacked responsibility. While ignoring his moral obligations on the Hakuna Matata parade, death itself swallowed up his kingdom. Simba was no neophyte—at least, up to this point. His father however was. Clearly, Mufasa has been initiated several degrees into the Mystery cult of celestial immortality. And now, with the ascended master’s appearing in the heavens, everything has changed. Simba, finally a true initiate of the Mysteries, must now master himself by gazing so intently at the heavens above that he ultimately punctures and penetrates deep within his very being and remembers who he is, and by doing so, journey into the sunless realm of death itself. Mortality must be hurdled back to the hyena’s realm.

And so, by closing credits, it is done.

In yet other terms, The Lion King is simply another retelling of the Mysteries of Isis. Simba’s parents, their names are Mufasa and Sarabi, are stand-ins for the paternal gods of Egypt, Osiris and Isis. Twins from conception, Mufasa and Sarabi, or rather, Osiris and Isis, were such perfect lovers that they conjugated within their mother’s womb. And as a pointed feature in the transmigration of souls, Osiris inherited his kingship form a divine lineage which he could trace back to Ra, creator of the world. A fellow initiate would likely hear Mufasa and Sarabi’s religious devotion to the Circle of Life and understand what they were inferring. After all, the ruling king and queen were children of the earth god Geb and the sky goddess Nut. Though it is true, upon dying, that their corpse would return to the earth god Geb, essentially becoming leaves of grass for the antelope’s consumption, it is also assured that their souls would simultaneously return to Nut, their mother goddess, and so, like the cyclical deposition and condensation of rain, the soul continues on in the Circle of Life.

But there was only one problem, Mufasa’s brother Scar—or rather, Osiris’ brother, Set.

Set was jealous. Osiris held his kingdom in perfect balance. And Set wanted it.

There is very little information provided in Egyptian literature regarding the specifics of Osiris’ reign. Within the Mysteries of Isis, it is his murder at the hands of Set and the devastating aftermath which grips the interest of her devotees. Osiris, you see, was not only a righteous king; his precedent materialized the rule of maat. For the Egyptian, the goddess Maat personified the ideal natural order—truth, balance, harmony, law, morality, and justice. Maat not only regulated the stars in the womb of their mother Nut and the seasons emanating from their father Geb, but managed both mortals and deities alike. Essentially, maat is best exemplified in The Lion King’s opening ceremony, when mortals pay homage to the cub born in the cave, like Mithras before him, and with the aid of the baboon shaman, is metaphorically ascended for the praise and reverence of all. However, with Set upon the throne of Osiris, the goddess Maat has apparently lost her authority. Order is therefore ruled by disorder—balance by imbalance. In her place the rule of Isfet materialized. In Egyptian terms, this simply meant injustice, chaos, violence and evil reigned supreme.

It is through Simba, or in this case Horus, child of Osiris and Isis and nephew of Set, in which the usurper might be defeated and Maat restored to the throne. Only through Horus might his father Osiris still live.

And so, you see, the Circle continues.

But do understand. The Lion King isn’t simply an outdated story highlighting our mythological superstitions of old. The esoteric, in one ear and out the other for most, is as far from lazy storytelling as one can get. For the initiate of every age, Isis and Horus is a parable embellishing divine providence. Though it is true, at present, that the Mysteries of Isis prompts us to gaze so intently into the firmament above that we are expected to discover the divine within; it also directs us towards what is expected to come.

Or as Rafiki, the witch doctor baboon, concluded for the Occulting hopeful:

“The king has returned.”

Roll end credits.

-Noel