Silver Chord = Silver Slippers… Cruel God = Humbug Wizard… | L. Frank Baum’s Transmissions from Oz (Part 2)

A DREARY KANSAS LANDSCAPE, MYSTICAL CYCLONE, and conscious-driven journey down the yellow brick road. It all adds up. L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz is an allegorical tale—albeit a subconscious one, arguably—outlining the soul’s path beyond the material plane to spiritual illumination. It has all the added spicy American ingredients to a far older tale of the occulting Mysteries. The Theosophical Society agrees. In 1986, The American Theosophist magazine recognized Baum as a “notable Theosophist,” a devoted ambassador for their philosophical and religious causes. As the 20th century neared its end, with decades of annual televised reruns of the MGM classic loyally garnishing the attention of nostalgic households, the cat was out of the bag. Dorothy was a neophyte.

“Although readers have not looked at his fairy tales for their Theosophical content, it is significant that Baum became a famous writer of children’s books after he came into contact with Theosophy. Theosophical ideas permeate his work and provided inspiration for it. Indeed, The Wizard can be regarded as Theosophical allegory, pervaded by Theosophical ideas from beginning to end. The story came to Baum as an inspiration, and he accepted it with a certain awe as a gift from outside, or perhaps from deep within himself.”

American Theosophist no 74, 1986

Baum’s son Frank later admitted the author’s devotion to Theosophy, but also maintained that his father “could not accept all its teachings. He firmly believed in reincarnation; he had faith in the immortality of the soul and believed that he and his wife had been together in many past states and would be together in future reincarnations, but he did not accept the possibility of the transmigration of souls from human beings to animals or vice versa, as in Hinduism. He was in agreement with the Theosophical belief that man on Earth was only one step on a great ladder that passed through many states of consciousness, through many universes, to a final state of Enlightenment. He did believe in Karma, that whatever good or evil one does in his lifetime returns to him as reward or punishment in future incarnations. He believed that all the great religious teachers of history had found their inspiration from the same source, a common Creator.”

The royal historian of Oz was well aware that his accomplishments as a storyteller was achieved through his ability to serve as a “medium,” or what the American Theosophist referred to as a gift from outside. “It was pure imagination,” Baum once told a reporter concerning Oz. “It came to me right out of the blue. I think that sometimes the Great Author has a message to get across and He has to use the instrument at hand. I happened to be that medium, and I believe the magic key was given me to open the doors to sympathy and understanding, joy, peace and happiness.”

Consider if you will, though somewhat lengthy, the Prologue to “The Patchwork Girl of Oz,” in which Baum writes:

“Through the kindness of Dorothy Gale of Kansas, afterward Princess Dorothy of Oz, a humble writer in the United States of America was once appointed Royal Historian of Oz, with the privilege of writing the chronicle of that wonderful fairyland. But after making six books about the adventures of those interesting but queer people who live in the Land of Oz, the Historian learned with sorrow that by an edict of the Supreme Ruler, Ozma of Oz, her country would thereafter be rendered invisible to all who lived outside its borders and that all communication with Oz would, in the future, be cut off.

The children who had learned to look for the books about Oz and who loved the stories about the gay and happy people inhabiting that favored country, were as sorry as their Historian that there would be no more books of Oz stories. They wrote many letters asking if the Historian did not know of some adventures to write about that had happened before the Land of Oz was shut out from all the rest of the world. But he did not know of any. Finally one of the children inquired why we couldn’t hear from Princess Dorothy by wireless telegraph, which would enable her to communicate to the Historian whatever happened in the far-off Land of Oz without his seeing her, or even knowing just where Oz is.

That seemed a good idea; so the Historian rigged up a high tower in his back yard, and took lessons in wireless telegraphy until he understood it, and then began to call “Princess Dorothy of Oz” by sending messages into the air.

Now, it wasn’t likely that Dorothy would be looking for wireless messages or would heed the call; but one thing the Historian was sure of, and that was that the powerful Sorceress, Glinda, would know what he was doing and that he desired to communicate with Dorothy. For Glinda has a big book in which is recorded every event that takes place anywhere in the world, just the moment that it happens, and so of course the book would tell her about the wireless message.

And that was the way Dorothy heard that the Historian wanted to speak with her, and there was a Shaggy Man in the Land of Oz who knew how to telegraph a wireless reply. The result was that the Historian begged so hard to be told the latest news of Oz, so that he could write it down for the children to read, that Dorothy asked permission of Ozma and Ozma graciously consented.

That is why, after two long years of waiting, another Oz story is now presented to the children of America. This would not have been possible had not some clever man invented the “wireless” and an equally clever child suggested the idea of reaching the mysterious Land of Oz by its means.”

L. Frank Baum.

“OZCOT” at Hollywood in California

For the occultist, his mind and the brain are not to be confused as one and the same. The brain is only an organ. It is a material mechanism which operates as a receiver on the physical plane. The mind however needs no use of the brain when it functions on other non-physical planes of existence. The brain itself is only required for the mortal, for his mind continues on into the metaphysical. Manas, what is known as “the Mind Principle,” is that connecting link between our pure, eternal, spiritual nature and our mortal, physical, material, personal nature. Writes Blavatsky: “Matter is spirit at its lowest level. Spirit is matter at its highest level.”

Dorothy Gale lives in Kansas. She’s an orphan. Kuthumi Lal Singh, one of Theosophies early teachers and which Baum would have likely been made well aware of, referred to humanity as “the great Orphan.” At any rate, Kansas is a stand in for our plane of existence—the material world. While “Over the Rainbow” is the MGM brainchild of composer Harold Arlen and lyricist Yip Harbur, most will agree that it is a faithful adaptation of Baum’s vision—conceptually speaking, despite the movie’s overarching depression-era message. Dorothy’s aspirations are to reach the ethereal realm. She is seeking a higher truth. And it is the cyclone who will grant her conscious wish. Over the rainbow, into a far more colorful tapestry of reality, she will go.

The Vigilant Citizen states (and I thank you for much of this information): “Dorothy is then brought to Oz by a giant cyclone spiraling upward, representing the cycles of karma, the cycle of errors and lessons learned. It also represents the Theosophical belief in reincarnation, the round of physical births and deaths of a soul until it is fit to become divine. It is also interesting to note that the Yellow Brick Road of Oz begins as an outwardly expanding spiral. In occult symbolism, this spiral represents the evolving self, the soul ascending from matter into the spirit world.”

The Encyclopedic Theosophical Glossary defines spiral:

“The path of a point (generally plane) which moves round an axis while continually approaching it or receding from it; also often used for a helix, which is generated by compounding a circular motion with one in a straight line. The spiral form is an apt illustration of the course of evolution, which brings motion round towards the same point, yet without repetition.

The serpent, and the figures 8 and sideways eight, denoting the ogdoad and infinity, stand for spiral cyclic motion. The course of fohat in space is spiral, and spirit descends into matter in spiral courses. Repeating the process by which a helix is derived form a circle produces a vortex. The complicated spirals of cosmic evolution bring the motion back to the point from which it started at the birth of a great cosmic age.”

In his book, “Secrets of the Yellow Brick Road: A Map for the Modern Spiritual Journey Based on The Wizard of Oz,” author Jesse Stewart notes that the unwinding spiral complements the cyclone by reversing the path of her involution.

According to Buddhism, which plays an important part of Theosophical teachings, the yellow brick road mirrors the “Golden Path,” or the “Middle Way.” Such a concept refers to Buddha’s view of life and describes the path that transcends and reconciles the duality characterized by cognitive thinking. One might consider it a universal pursuit of all Buddhist traditions—the quest for a way of life that would give the greatest value to human existence and help relieve the world of suffering. To this Stewart adds: “Her three companions represent both three aspects of the human personality (thinking, feeling, and will) and the three paths of Yoga: knowledge, devotion, and action….Dorothy and her companions wander off the Path, however, and come to a broad river; they try to cross to the other side (shades of Buddhist metaphor), but find themselves in deep water, drifting out of control. Eventually they get to land and enter a field of soporific poppies; the flowers are like those in the Hall of Learning of The Voice of the Silence: ‘the blossoms of life, but under every flower a serpent coiled.’”

We must forget all about Dorothy’s ruby slippers. MGM’s The Wizard of Oz was a product of Technicolor, and they needed their price of admission. The slippers of Baum’s transmission have a higher esoteric wealth, for they are silver. It is of no coincide that Dorothy receives her shoes upon arrival in Oz, and that they alone hold the power to ensure her trip home. The silver shoes represent the “silver cord” of the Mystery Schools; a vital lifeline between our material and spiritual selves which the Neophyte must learn to master. Dorothy’s enlightenment is begun by defeating the wicked witch of the East, whom the shoes once belonged to, and is certainly heightened of her refinement by killing the wicked witch of the West. Together they formed an “evil horizontal axis: the material world.” Dorothy’s ultimate illumination likely results from her association with the good witches of the north and south: “the vertical axis” or “the spiritual dimension.” In his book, “Finding OZ: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great America Story,” author Evan I. Schwarz writes:

“In Theosophy, one’s physical body and one’s Astral body are connected through a “silver cord,” a mythical link inspired by a passage in the Bible that speaks of a return from a spiritual quest. ‘Or ever the silver cord be loosed, says the book of Ecclesiastes, ‘then shall the dust return to the earth as it was and the spirit shall return unto God who gave it’. In Frank Baum’s own writing, the silver cord of Astral travel would inspire the silver shoes that bestow special powers upon the one who wears them”

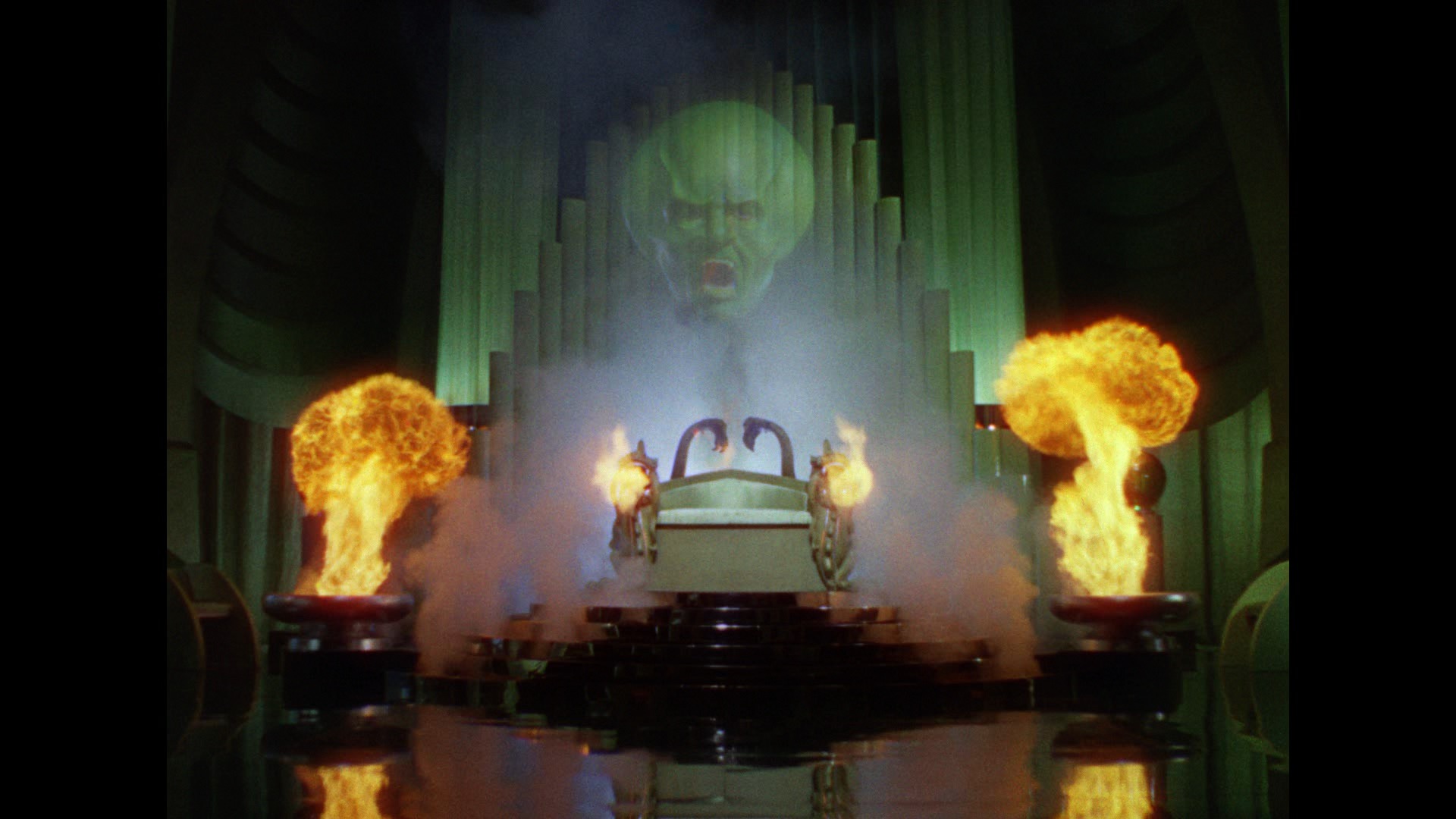

God shows up in Dorothy’s journey as well, and with unexpected though “enlightening” consequences. But He is not the “common creator” of occultist lore. No, this God is oppressively cruel. The Creator of the Bible is an enemy of Theosophy. By convincing everyone to wear glasses with “emerald shades,” so as not to succumb to blindness when staring at his glorious city, the Wizard has cast the wickedest of spells—spiritual ignorance. For you see, the Emerald City is not so glamorous after all, should the glasses chance to come off. Despite all of his menacing special effects, the Wizard is a humbug. He is incapable of fulfilling any task except to scare the ignorant into worshiping him.

But thank the “common creator” for Toto. Concerning the most popular Cairn terrier who ever was, the Theosophical Society’s website writes:

“Toto represents the inner, intuitive, instinctual, most animal-like part of us. Throughout the movie, Dorothy has conversations with Toto, or her inner intuitive self. The lesson here is to listen to the Toto within. In this movie, Toto was never wrong. When he barks at the scarecrow, Dorothy tries to ignore him: “Don’t be silly, Toto. Scarecrows don’t talk.” But scarecrows do talk in Oz. Toto also barks at the little man behind the curtain. It is he who realizes the Wizard is a fraud. At the Gale Farm and again at the castle, the Witch tries to put Toto into a basket. What is shadow will try to block or contain the intuitive. In both cases, Toto jumps out of the basket and escapes. Our intuitive voice can be ignored, but not contained.

In the last scene, Toto chases after a cat, causing Dorothy to chase after him and hence miss her balloon ride. This is what leads to Dorothy’s ultimate transformation, to the discovery of her inner powers. The balloon ride is representative of traditional religion, with a skinny-legged wizard promising a trip to the Divine. Toto was right to force Dorothy out of the balloon, otherwise she might never have found her magic. This is a call for us to listen to our intuition, our gut feelings, those momentary bits of imagination that appear seemingly out of nowhere.”

It is a sad but likely scenario: Christianity’s gradual demise in western civilization is resulted in part from its numbing down to the very mystics who flagrantly oppose the God they claim to serve. A willing partnership, all for the sake of entertainment—even in its most playful and child-like distribution—is hardly arguable here. “In God we trust” is imprinted on the US dollar and the esoteric supermarket will have it. Occultism sells. The results show. Yet there will be few still remaining in the pews that’ll read this and find the moral outrage—that is, unless their allocation of justice is directed away from the obvious perpetrators and against my audacity to strike a match and flick the flame towards their conscious. How do I know this? I’ve already been told with the raised nose of a passive-aggressor—in fact, many—and will surely be reminded again (I have little to no doubt about it):

“It’s clear that imaginative storytelling is not for everyone.”

No, I suppose not.

Can you believe it? I was once a collector of first and early-edition Oz books. But that was back in the days when I could look Christianity’s perpetrators in the face and think little to nothing of it.